Can sculptures ever speak to us?

Can they transcend their silent natures and inspire in us those emotions that make us human – love and hate, hope and despair? The greatest minds and most virtuoso hands of the Renaissance were driven to distraction with this very question, and sculptors from Donatello to Michelangelo to Bernini spent their entire lives trying to confer the spark of life to their marble creations. But how could cold and unfeeling stone touch the heart? The answer awaits us in one of the most suggestive corners of the Vatican Museums.

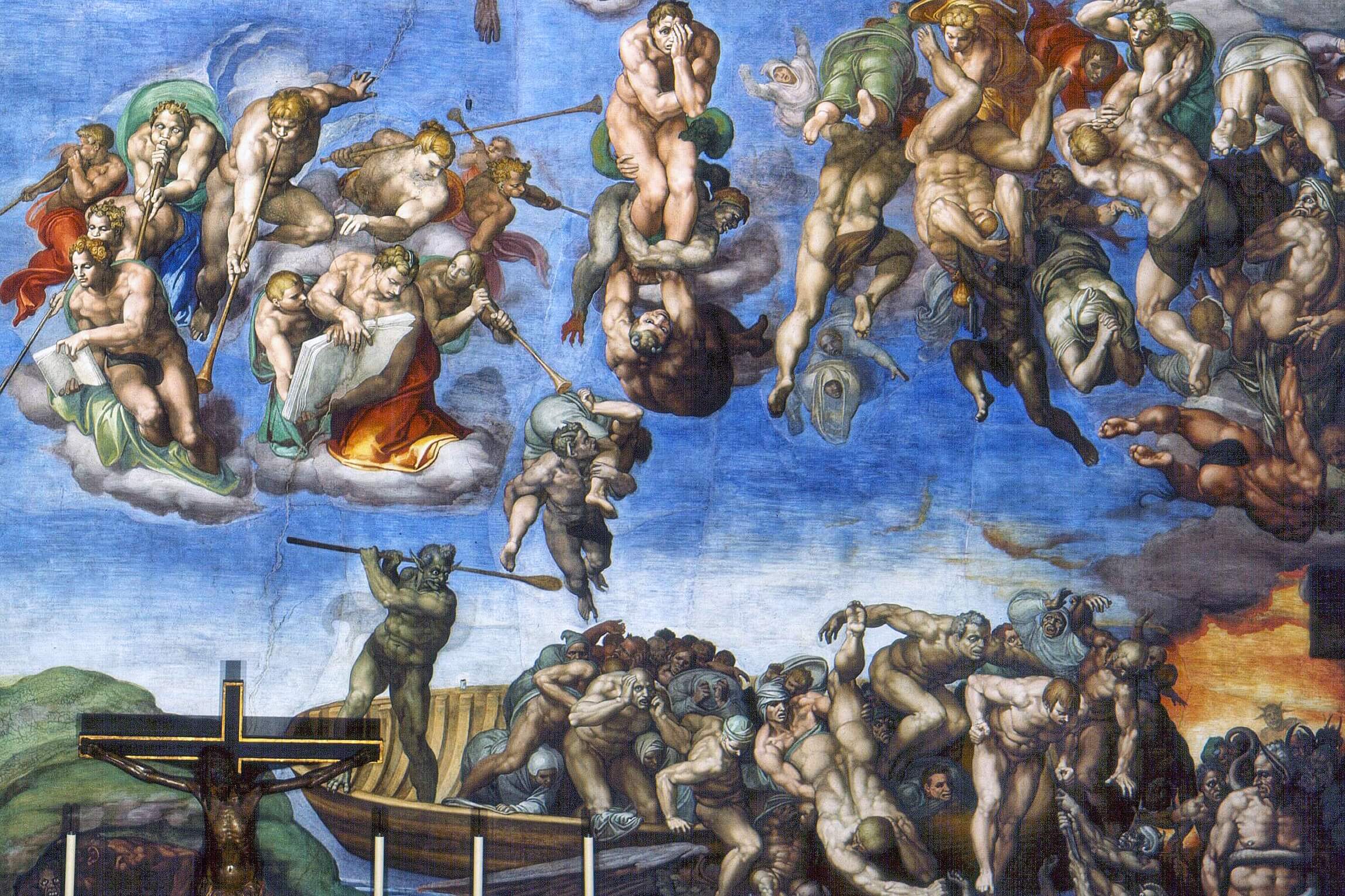

Discover the Sistine Chapel

Join a Vatican Tour

But first, some context. Did you know that despite being at the very epicentre of the Catholic world, The Vatican Museums has far more to offer than Christian art? More than willing to overlook their pagan subject matter, the most powerful popes of the Renaissance were also avid collectors of classical sculptures, and each new incumbent to the throne of St. Peter in the 16th century was keen to add to the Papal collection. The ancient marbles that line the halls and fill the courtyards of the Vatican palace today were to have an enormous influence on the evolution of art in the Renaissance, and artists from Michelangelo to Raphael and beyond flocked to Rome to study them.

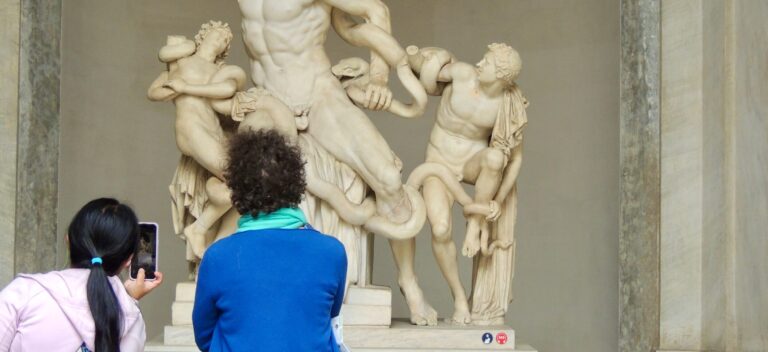

The core of this collection today is housed in the Vatican’s Octagonal Courtyard, a beautiful sculpture-garden founded by Pope Julius II in the first decade of the 1500s. Standing in pride of place here is the Laocoön, an incredibly dramatic Hellenistic sculpture depicting a battle between a Trojan priest and his sons against divinely sent sea-snakes during the Greek-Trojan war that is a must-see on any tour of the Vatican Museums. This masterpiece of psychological intensity was described as one of the ancient world’s greatest statues by the classical writer Pliny, and when it was rediscovered buried in a muddy vineyard at the start of the 16th century, the Pope resolved to have it hauled to the Vatican for his personal collection. Discover the fascinating full story of the Laocoön with us!

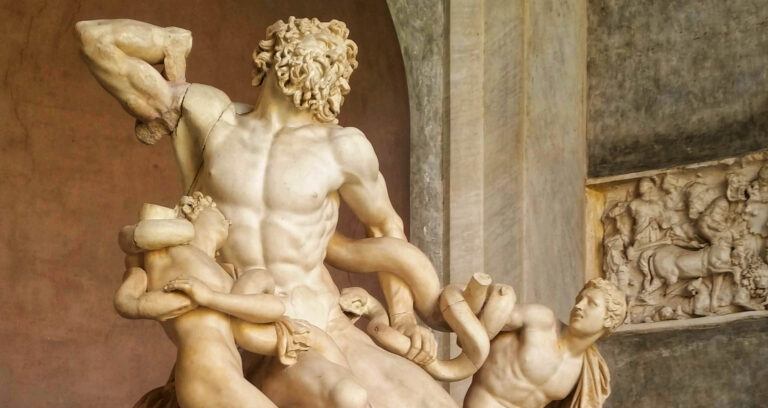

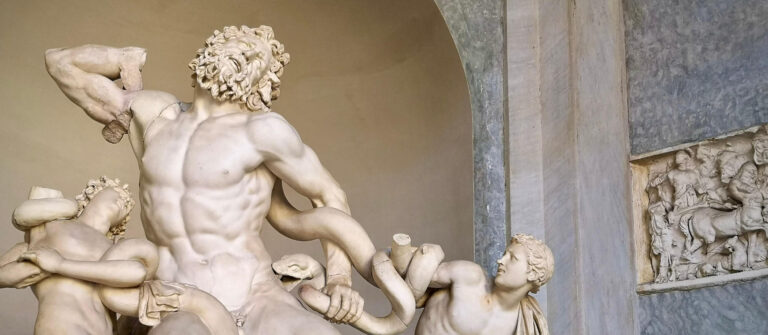

It is, perhaps, one of the most primal expressions of human anguish in the history of western art, an overflow of raw emotion that explodes out of the calm surroundings of the Vatican’s Octagonal Courtyard and destroys a hundred myths about the restrained nature of the classical world. This is the Laocoön, one of the true unmissable highlights of the Vatican’s sculptural collection. At the centre of this marble group an immensely muscular figure writhes in agony as a serpent tears at the naked flesh of his hip and wraps itself around his body. Despite his obvious strength, the man is powerless to resist. Two young boys are also ensnared in the serpent’s coils, struggling in vain to free themselves from its clutches. But our eyes are inevitably drawn back to the terrifying face of the shaggy and bearded man whose head is thrown back in a howl of immeasurable anguish that seems to emanate from the depths of his very soul.

This sculpture captures one of the most dramatic moments of one of the most dramatic narratives in the Western canon. Helen, by popular acclaim the most beautiful woman in the world, has been carried off from her native Sparta to the city of Troy by the love-struck Paris. The Greeks, fired by fantasies of revenge, set off in hot pursuit, and hatch a cunning plan to breach their enemy’s city fortress. Offering the Trojans a massive wooden horse as a spurious peace-offering and symbol of their defeat, a crack unit of elite Greek soldiery are in fact hidden inside the hollow structure as it is wheeled into the city. But not everyone is taken in by the subterfuge; the Trojan priest Laocoön sees through the ruse, desperately warning his compatriots with the immortal caution ‘I fear Greeks, even those bearing gifts.’

Pope Sixtus sought an elevated pedigree for the crowning achievement of his reign, and he found it in the model of the ancient Temple of Solomon built in Jerusalem in 966 B.C. as outlined in the Hebrew Book of Kings. Both structures are twice as long as they are high, and three times as long as they are wide. But whereas Solomon’s temple was covered with cedar and gold, amongst the most precious materials known to the ancient world, the Sistine Chapel was covered with the most valuable intangible commodity of the Renaissance – the painted creations of its greatest painters.

During the first campaign of decoration the finest artists of Tuscany and Umbria descended on Rome to play their part, including Botticelli, Perugino and Ghirlandaio, whose beautiful frescoes depicting the lives of Moses and Jesus stretch all along the side walls of the chapel. To make the link between the Sistine Chapel and the Temple of Solomon explicit, Perugino’s fresco of Christ giving the keys to St. Peter makes explicit reference to Solomon’s temple in an inscription.

As it was for those artists stupefied by the find in a muddy vineyard 500 years ago, Laocoön remains a staggering achievement of the sculptor’s art and a worthy object of pilgrimage for visitors to the Vatican museums. The cardinal Jacopo Sadoleto described in 1506 how his soul was ‘horror-stricken at this sight of this mute image that hammers into my heart,’ and the primeval howl of anguish fixed for all time in the statue’s stony features still has the capacity to speak a powerful language of emotion and pathos today. Make sure you give it a second look on your way through the remarkable Vatican Museums.

To learn more about how to plan your perfect visit to the Vatican Museums, check out our in-depth guide to the masterpieces and hidden treasures of the Vatican below:

Ready to visit the Vatican?

Book Your Tour Here!