Hag of articulate wood, before Donatello found you, how many leaves did you watch detach themselves from your twigged fingers, how many branches stripped and nailed to make each crucifix?

– Linda Pastan

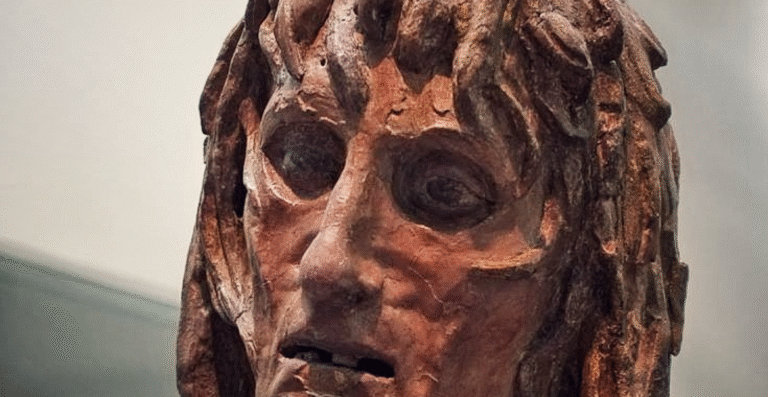

A haggard old woman stands before us, hollowed eyes sunk deep into an emaciated face, her mouth full of broken teeth. Tottering unsteadily on spindly legs, she is wreathed in tattered rags that hang loosely from aging skin. Twisted tresses of matted hair fall lankly from her scalp, coiling idly around her face. So withered and worn is she that one writer has called her a mummia vivente – a living mummy.

She is a tough old bird too, though – knotted muscles and veins pulse just beneath the skin of her arms as she raises her hands in a gesture of pious prayer. She has the lean strength of an old battler; a survivor. But who is this wasted apparition, this ‘hag of articulate wood’ more tree than woman, mixed in with the fabulous works of Renaissance art in Florence’s Museo dell’Opera del Duomo?

Florence Tours

Explore Donatello's Florence

Perhaps surprisingly, the larger-than-life-sized woman whose haunted gaze seems to follow our own is none other than Mary Magdalene, renowned as one of the most beautiful women in the New Testament. According to the most commonly accepted version of her life known to the Renaissance, Mary was a one-time prostitute and later faithful disciple of Jesus Christ, the first person to see him in the flesh after his miraculous Resurrection. Generations of artists picked up their brushes to portray the young and beautiful sinner converted to the stable of God, her sensuousness justified by newly spiritual urges – most famously Titian painted her in a state of tantalizing near-nudity for the delectation of the Duke of Mantua (above), her curves only partially covered by long locks of luscious blonde hair cascading down her body.

The gaunt figure that Donatello hacked out of a white poplar tree in the 1450s bears no traces of such sensuality, no hint of seductive charm. As the years went by, Magdalene’s life took a decisively ascetic turn. Victims of the capricious winds of fate, pious legend recalls that she and her sister Martha landed in Marseilles on a rudderless ship, with only their faith to sustain them in this strange land.

For the next 30 years, Mary lived the life of a hermit in the wilderness of Aix-en-Provence (not yet the charming painter’s retreat of the Impressionists). Turning her back on the material world entirely, Magdalene devoted herself to asceticism with an unmatched zeal, flagellating herself and undertaking punishing fasts. According to many Renaissance writers she survived for those three decades of isolation without any food at all, nourished only by immaterial ‘heavenly meats’ carried down from on high by well-wishing angels. It was here, amidst the dust and stones, that her reputation as one of the brightest stars in the saintly firmament was established, and centuries later she became one of the great paragons of a penitential mindset for the early-modern Church.

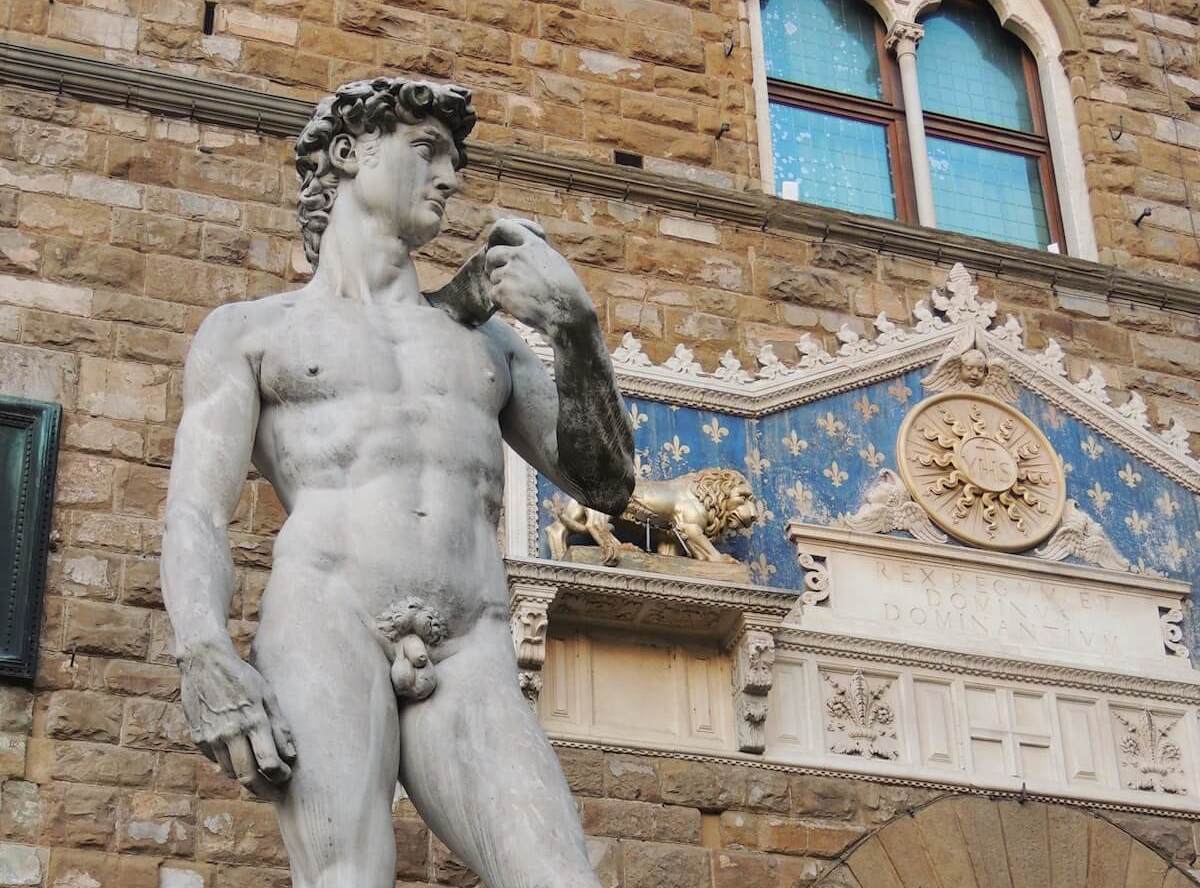

This is the Magdalene who looms before us, star of the ultimate repentant sinner narrative, wild and haggard from decades exposed to the harshest excesses of the elements – blinding rains, burning suns and whiplash winds. It was a narrative that fascinated Renaissance Florentines – it’s impossible for us to imagine just how present the saints were in the daily life of early-modern Italians, and just like other Biblical paragons that Donatello sculpted like his extraordinary David and stoic St. George, Magdalene was wildly popular.

Her story would have been intimately known to every Florentine, young and old, man and woman; it was recounted from the pulpit in Sunday sermons, on feast-days and in the apocalyptic speeches of itinerant preachers come to spit visions of hellfire to rapt audiences in the city’s streets and squares. Above all her presence loomed large in a raft of sacred images that covered countless religious and secular spaces all across Florence, vivid but silent reminders of her devoted holy life and miraculous repentance.

Mary owed her popularity in no small part to the ease with which her story could be adapted as an example for the faithful to live by. She was especially venerated by the Franciscan and Dominican Orders, who saw in her penitential excesses during that long spell in the wilderness a paradigm of how women could overcome their wicked ways and base desires. But this wasn’t just a patriarchal fantasy, and contemporary women really did feel a profound affinity with Magdalene.

For Renaissance Catholics, Mary Magdalene had got one over on the devil by turning away from sin and towards Christ, and Satan despaired that this beautiful woman had slipped through his clutches. Frequently accompanying images of Magdalene was an inscription that made clear exactly why she became such a popular role model: ‘there is no need to despair, even for you who have lingered in sin; ready yourselves anew for God!’ Mary’s carnal transgressions weren’t to count against her in the final reckoning, and gave hope to women looking to make their own peace with God here on earth.

The road to salvation awaits everyone who is open to God; but as Donatello vividly reminds us, this is a path littered with physical deprivation and psychological torment. The sculptor certainly pulls no punches: his Magdalene is in the throes of mental turmoil, he tortured physical form reflecting an indescribable spiritual anguish writhing within. The passing years have done little, it seems, to relieve her grief, inconsolable at the wicked depths to which her fellow humans sank in leading Christ to his bloody end.

The Magdalene is beaten by wretched time, by the rigours of the wilderness, by the harrowing path she has taken through life. And yet she’s still here, erect and defiant in the face of it all, unbending still. Her inscrutable gaze seems to be looking far into the distant past. What is she thinking of? Her opulent life as a courtesan (pictured so memorably by Caravaggio, above)? The first moment she saw Christ and experienced the divine rapture of conversion? The years following him faithfully as he spread the word across the world? The indescribable horror of Christ’s bloody body, so deformed that it hardly registered as human, nailed to a cross atop Golgotha, the hill of skulls? Or the unimaginable joy of seeing him healthy and whole once again, strolling along the roads of Jerusalem after his Resurrection?

All this, and more. Those are eyes that have seen all there is to see in this world and beyond; this is a body who has experienced all there is to experience in this life and the next. That Donatello could render all that in the inert wood of a white poplar tree is a testament not only to the greatness of his artistic vision, but the profound eye he cast upon the deepest recesses of the human psyche. Renaissance art, as if you needed any convincing, is about far more than just pretty pictures.

Experience the Best of Florence