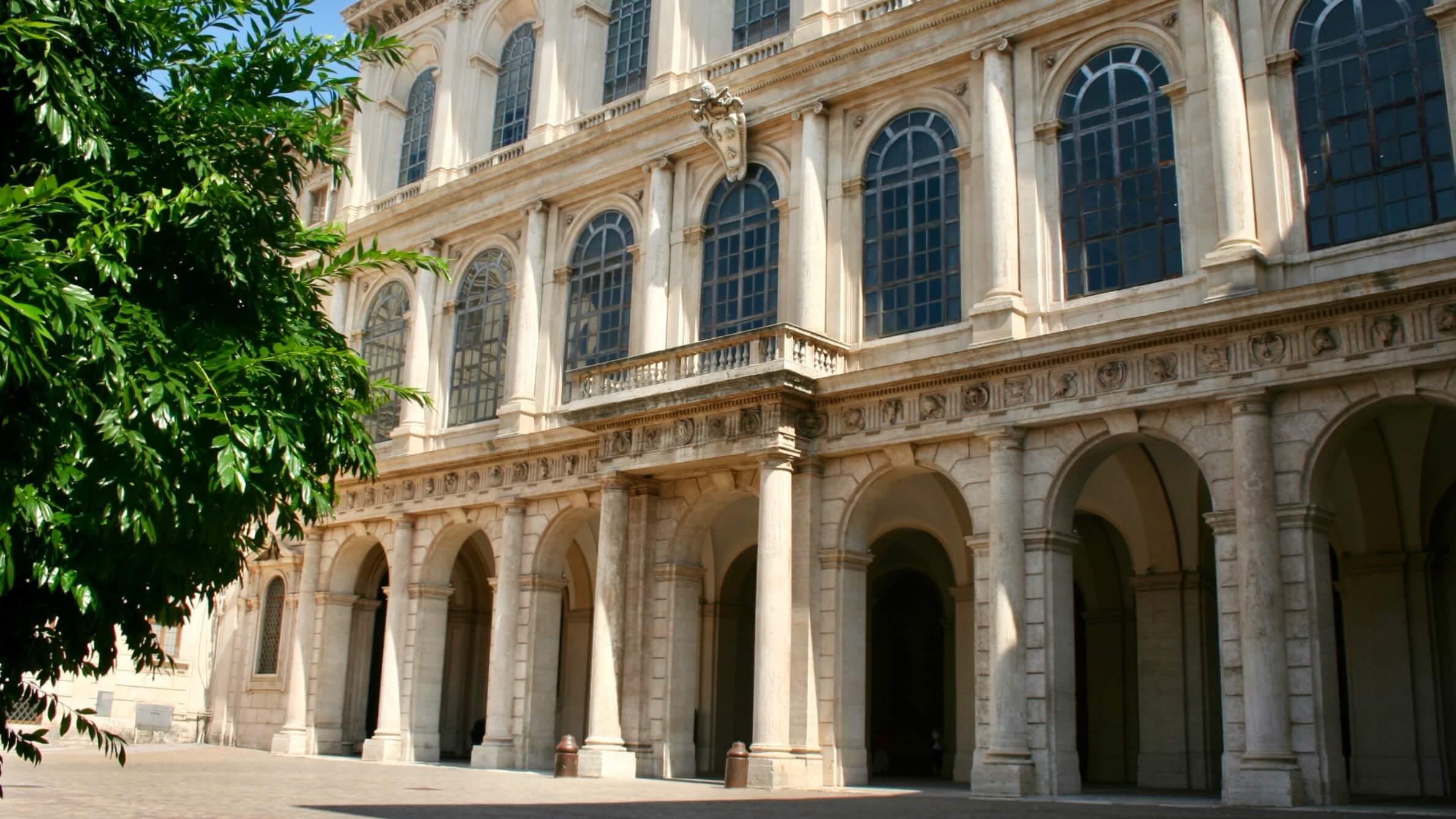

Tracing its origins all the way back to 1471, when the Renaissance Pope Sixtus IV donated a magnificent group of ancient bronze sculptures to the people of Rome, the Capitoline Museums is the oldest public collection of art in the world.

And what a collection it is! Spreading out over two Michelangelo-designed palaces atop the Campidoglio – the Palazzo dei Conservatori and Palazzo Nuovo – hall after spectacular hall is filled with stunning ancient sculptures and antiquities. The Capitoline Museums are an absolute must-see when in Rome. To help you get started planning your visit, this week on our blog we’re profiling the works that you need to see on a tour of the Capitoline Museums.

Rome Tours

Visit the Capitoline Museums

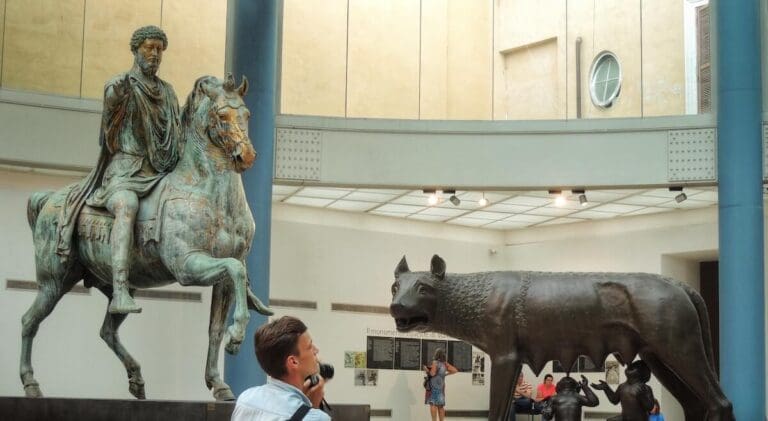

Known to both history and contemporaries simply as ‘the philosopher’, Marcus Aurelius ruled Rome between 161 to 180 AD. As the last of the so-called ‘good emperors,’ he presided over the empire during the final years of the Pax Romana, an unusually stable period of Roman history. Gazing imperiously over Rome from a commanding position on the Campidoglio outside the Capitoline Museums, this beautiful equestrian statue was probably erected to celebrate Marcus Aurelius’s victory against the Germans in 176AD.

Of the twenty-two “equi magni” (literally “big horses”, as the equestrian portraits of the emperors were called) that one graced ancient Rome, this is the only one to have survived to the present day. For centuries it was held to be a representation of Constantine, the first Christian emperor of Rome, and this mis-identification has protected it from being melted down for its precious bronze for over a millennium and a half.

Exuding power, the emperor is perched serenely on horseback and seems to be gesturing towards imagined subjects all around him. The original location of the statue is still debated: some scholars suggest that it might have been in the Forum while others think that it was probably located close to the column of Marcus Aurelius. At any rate, during the Middle Ages it was moved to the piazza in front of San Giovanni in Laterano, and in 1538 the statue was finally relocated to the beautiful Piazza del Campidoglio during the square’s renovation by Michelangelo.

The statue we admire today in the Piazza del Campidoglio is a replica created by the experts of the Italian National Mint – the original was moved inside in 1981, where it occupies pride of place today in a specially designed exhibition space at the heart of the museums.

As much as Marcus Aurelius was admired by contemporaries and subsequent generations alike, his successor Commodus was reviled in equal measure. Capricious, thin-skinned, vain and cruel, amongst his many excesses Commodus was known for his enthusiastic patronage of the brutal games at the Colosseum. Although his participation in gladiatorial combat as portrayed in the Ridley Scott epic Gladiator is likely an embellishment (despite his boast that he had won an incredible 12,000 bouts over his ‘career’), Commodus did indeed step out onto the Arena to slaughter beasts in wild animal hunts.

So proud was he of his exploits in dispatching wild animals that Commodus frequently had himself depicted as a second Hercules – as in this sculpture in the Capitoline Museums – complete with lion’s pelt and club.The emperor was not, however, fighting fair: in all likelihood the animals were tied up and didn’t have the opportunity to fight back, and Commodus remained safely distant on a raised platform firing arrows at them. Once, according to Cassius Dio, the emperor personally picked off a hundred bears as a warm up act to the games. One of his favourite tricks was decapitating ostriches with his arrows, then tossing their heads into the crowd.

A work of powerful pathos, The Dying Gaul portrays a stricken warrior succumbing to death as he buckles to the ground, blood streaming from his magnificently chiselled torso. Perhaps never before had a fallen enemy been depicted with such nobility or courage even in defeat; the warrior’s face, complete with wonderfully manicured moustache, radiates a quiet calm in the face of mortality, and it is clear that the sculptor saw much humanity in the vanquished foe. The sculpture is a Roman copy of a lost Greek original in bronze, created for the decoration of the Sanctuary of Athena in Pergamon and brought to Rome by Nero. Lord Byron (who thought the sculpture depicted a gladiator) immortalised the stoic courage of the figure in his poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, describing how

‘I see before me the gladiator lie

He leans upon his hand—his manly brow / consents to death, but conquers agony.’

You’ll come face-to-face with the men who made Rome in the breathtaking Hall of Emperors, where row upon row of lifelike marble busts stare down at us across the centuries. The 67 imperial portraits come from the Albani collection, which was purchased by the Museums in 1733, and the glittering hall that houses them has changed little since.

In addition to providing a valuable history of the evolution of sculptural style in antiquity, it’s extremely entertaining to pick out individual emperors and speculate on their characters; look out for the mad glint in sneering Nero’s eye, or the studied calm of Augustus and the flinty gaze of his formidable wife Livia. Vespasian, who commissioned the Colosseum, has the ruddy good humour you’d expect of a man of the people, whilst you’ll be able to pick out Hadrian as the first emperor to sport a beard. The thuggish good looks of Caracalla, meanwhile, signals him as a man not to cross: and indeed, after murdering his brother to ascend to the throne, he unleashed one of the most tyrannical reigns in the history of Rome.

The adjacent Hall of Philosophers offers up an intellectual mirror image to the Hall of Emperors. Here the crinkled eyes and furrowed brows of the finest thinkers of classical antiquity stare soberly into the room, from Socrates to Cicero, Homer to Pythagoras. These sculptures once adorned the lavish gardens, palaces and libraries of Rome’s culture-loving aristocracy, who idolised the intellectuals of antiquity.

Gaze on her if you dare…The terrifying Medusa might just be ancient mythology’s most dangerous woman – her hair a tangle of writing snakes, Medusa’s deadly stare had the legendary power to turn anyone who gazed upon her dread visage to stone. In a great visual joke, Baroque master Gianlorenzo Bernini turned Medusa’s power on herself when he carved her in marble in the 1640s, neutering the Gorgon’s danger as he entrapped her forever in stone.

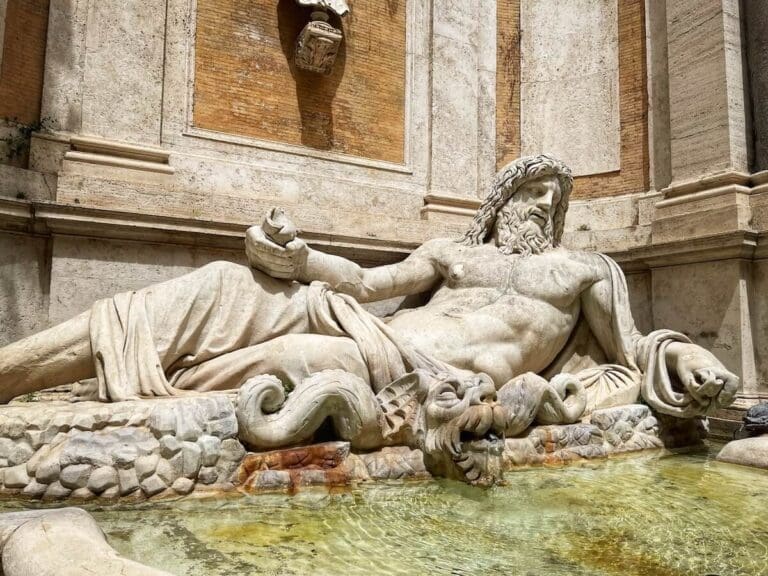

One of Rome’s so-called ‘speaking statues,’ the colossal river-god Marforio reclines lazily in a fountain in the courtyard of the Palazzo Nuovo. One of the few antique sculptures that was visible in Rome during the Middle Ages, the massive figure took on an important role in early-modern Rome as a member of the city’s ‘Congregation of Wits’ – ancient sculptures who were adopted by the populace as mouthpieces to express inexpressible political opinions or critiques of the ruling classes via anonymous satirical poems affixed to their plinths.

Marforio kept up a centuries-long dialogue with the statue of Pasquino across town near Piazza Navona, and the records of their ‘conversations’ offers fascinating insights into life in the early-modern city. Numerous popes became furious with their anonymous critiques, with various plans to dismember the statues or toss them into the Tiber. All to no avail; the speaking statues continued to speak, and Pasquino is still covered with witticisms and satires to this day.

One of the most admired of all ancient sculptures, the Capitoline Venus has become synonymous with the refined values of classical art. Delicately carved from resplendent Parian marble and based on a Greek prototype by the renowned sculptor Praxiteles, the statue portrays the goddess of love emerging naked from her bath, partially covering her nudity with her slender hands.

With her refined, complicated hairstyle, strong features and voluptuous figure, the Capitoline Venus has enraptured generations of visitors to Rome since its discovery in the 1660s, and Napoleon had it carted off to Paris during the French occupation of the city at the end of the 18th century. Thankfully, the original returned to the Capitoline Museums in 1816, where it occupies pride of place in the beautiful octagonal Cabinet of Venus.

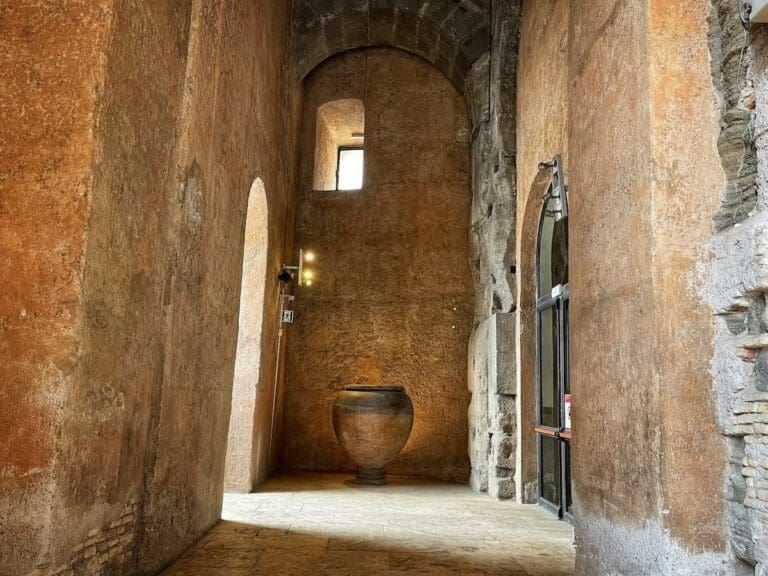

One of our favourite spots in the Capitoline museums is one of its quieter corners – the soaring Tabularium was an ancient Republican era building set into the rock of the Capitoline hill where the bronze tablets of ancient Roman law were reverentially preserved, and today forms the basement of the Museums. The views of the Roman Forum from here are second to none, and the atmosphere of the Tabularium is rich with the mysteries of antiquity.

The she-wolf is Rome’s iconic symbol, who according to legend suckled the abandoned infant twins Romulus and Remus before being adopted by the herdsman Faustulus and going on to found the city on the Palatine Hill. The image of the she-wolf suckling Romulus and Remus is a symbol of Rome since ancient times and one of the most recognizable icons of ancient mythology.

This magnificent bronze statue of the wolf was one of the artworks donated to the people of Rome by Pope Sixtus IV in 1471, and so one of the founding pieces of the collection. Although some scholars argue that the the wolf is a work of the Middle Ages, the consensus remains that it is probably of Etruscan origins, and in its original context had nothing to do with the mythical founding of Rome – the infant twins were added to the ensemble sometime in the 15th century.

The unusual pose of this small antique bronze statue of a boy pulling a thorn from the sole of his foot was to have an outsize influence on the art of Renaissance. Measuring just 73 cm high, the sculpture had been rediscovered at least by the 12th century, and was donated to the people of Rome by Pope Sixtus IV in 1471. The work was widely admired and copied in the early-modern period. A popular legend maintained that the sculpture depicted the ancient shepherd boy Marzio, who ran all the way from Vitorchiano near Viterbo to Rome in order to warn of an impending invasion by Etruscan forces.

The youth only stopped once on his 70 kilometre dash, to remove a thorn from his foot. Mission completed, the exhausted Marzio died on the spot. So struck was the Florentine artist and architect Brunelleschi by the motif that he included it in his design for the door of the city’s Baptistery in his famous competition with Lorenzo Ghiberti in 1401.

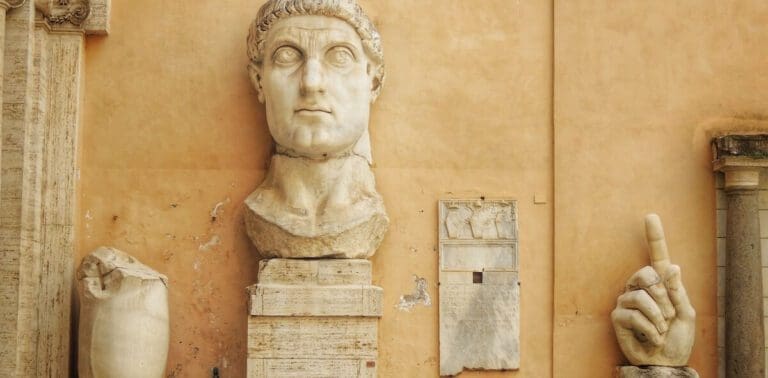

Put your hands in the air for Constantine…the colossal hand that greets visitors to Rome’s Capitoline Museums must be one of the world’s most impressive appendages. Standing (if that’s the right word) at over five feet high, the incredibly naturalistic right hand with raised index finger originally formed part of a seated statue of Rome’s first Christian emperor that towered more than 40 feet into the sky.

The Colossus of Constantine first stood in the Forum’s imposing Basilica of Maxentius – Constantine had defeated Maxentius at the battle of the Milvian bridge in 312 AD, and by adorning the building bearing his rival’s name with a monumental statue of himself the now sole emperor left all of Rome in no doubt as to who had triumphed. More than 1700 years later, the massive piecemeal remains still radiate a crystal clear message – here was a man who mattered.

This jaw-droppingly beautiful ancient mosaic captures the amazing attention to detail and observational skill that characterised the art of Imperial Rome at its peak. The colourful mosaic depicts four doves perched on the edge of a golden bowl as one leans over the rim to slake its thirst.

Look out for the ripples in the water and the reflections in the bowl’s metal. The mosaic originally adorned Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli, and was rediscovered during excavations in 1737. It is probably a 2nd-century AD Roman copy of an original mosaic by the Greek artist Sosus of Pergamon, a work widely lauded in the ancient world and said to be so realistic that doves crashed into the mosaic in an attempt to perch alongside their fellow birds.

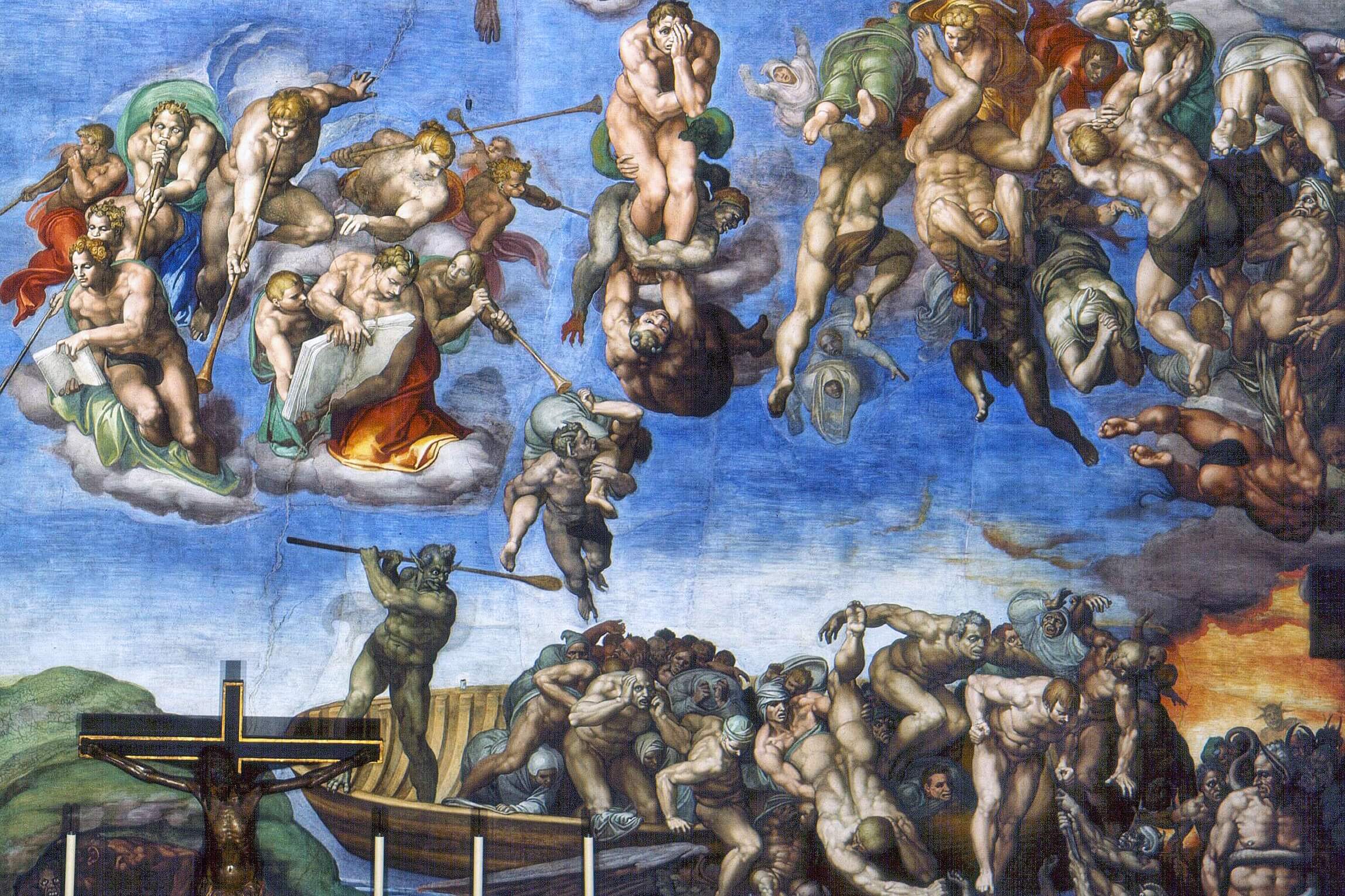

Even if you find your energy flagging, don’t miss out on the painting gallery located on the upper floor of the Museums. This extremely underrated collection is home to some of Caravaggio’s finest early genre pieces – here a fortune teller traces the future of a young dandy in the lines of his palm as she slips a ring from his finger; there, a boy yelps in pain as his finger is nipped by a lurking lizard. Also in the gallery are masterpieces by Guercino, Rubens, Pietro da Cortona and many more.

Essential Rome Tours

Through Eternity offer expert-led guided tours of the Capitoline Museums. Navigating the seemingly endless halls of masterpieces on your own can be overwhelming for even the most seasoned history buff – our expert guide will lead you through the maze and take you straight to what you need to see, weaving a fascinating tale of the power, art and intrigue of antiquity along the way!