Mentioning Daniele da Volterra in art circles is a risky business, much like praising Dan Brown at a literary seminar.

Better to whisper it quietly, for you are more likely to be greeted with snorts of derision than sighs of admiration. Though one of the most renowned artists of his generation, his name has for centuries conjured up images of Counter-Reformation prudery, censorious inquisitors and artless fundamentalists. Posterity, alas, has not been kind to the man from the Tuscan foothills.

Rome Tours

Find Your Perfect Rome Itinerary

To uncover the reason for 400 years of disdain, we need look no further than Daniele’s unfortunate nickname. From Masaccio to Botticelli and Parmigianino, an entire history of Italian art could be written through the frequently ingenious sobriquets of its brightest stars. Daniele da Volterra is better known to history by the derogatory title “Il Braghettone,” or the breeches-maker.

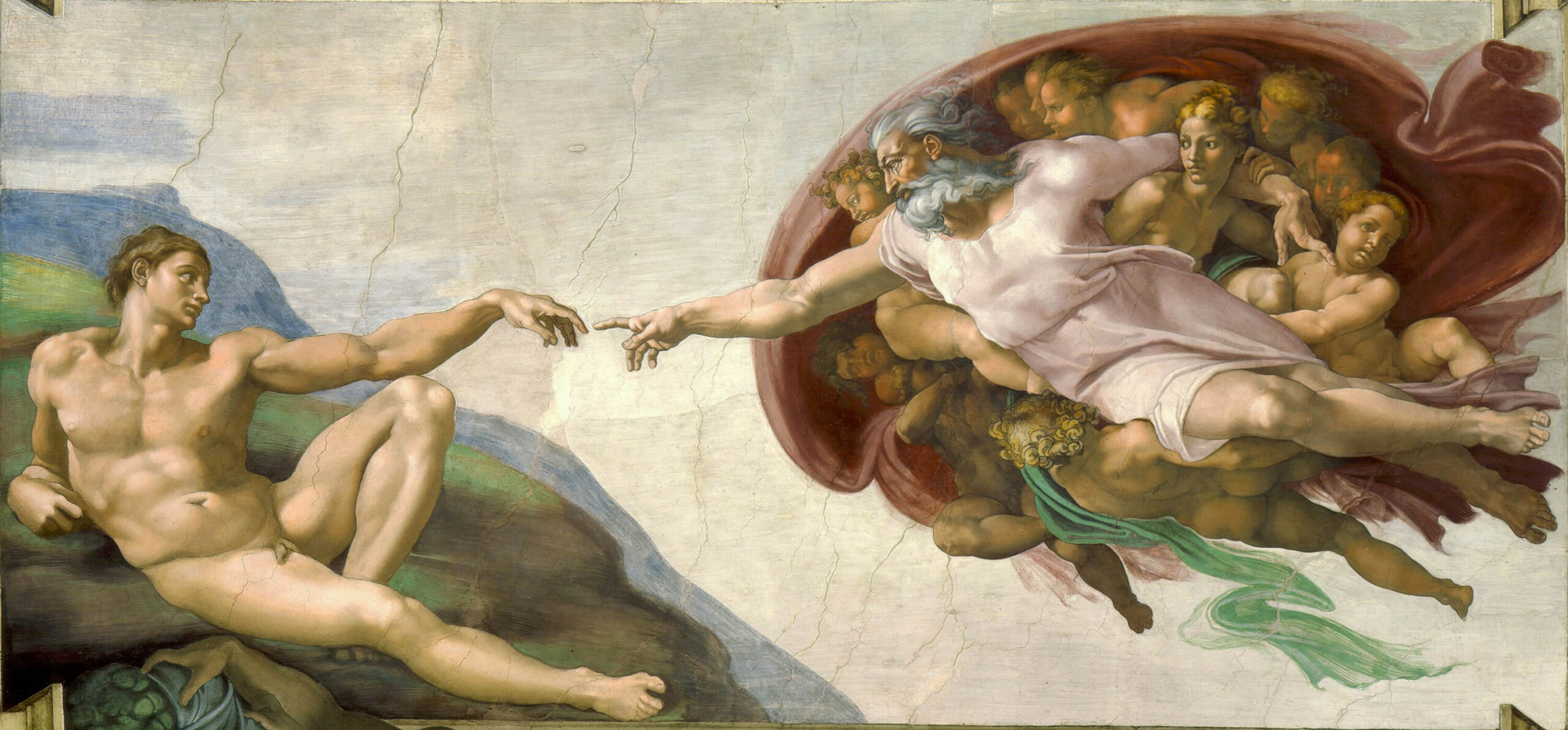

No mere snobbish slur, the breeches in question referred to one of the most infamous commissions in the history of art. For it was to Daniele that the puritanical popes Paul IV and Pius IV turned when it was finally decided to cover the shameful nudity of Michelangelo’s Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel in 1564, the year of the artist’s death. Daniele duly sheathed the heaving mass of naked sainthood in a variety of morally improving underwear, and was duly rewarded in the court of public opinion with his demeaning moniker.

Ironically, this most notorious defacer of Michelangelo’s work was in reality one of this cantankerous old Florentine’s few friends in Rome. He was there at the great artist’s death, where he read out the story of Christ’s crucifixion again and again at the dying man’s request. The finest likenesses of Michelangelo to have come down to us are from the hand of Daniele, one a magnificent portrait bust and the other a drawing of subtle and melancholic intensity.

His posthumous reputation as nothing more than a prudish defiler seems a harsh judgement indeed. For who could defy the commands of a pope as fierce and ascetic as Paul IV – a man so conservative he was known to have spent his days castrating ancient sculptures in the Vatican palaces? Without his intervention, in fact, it is quite likely that the Last Judgement would have been destroyed altogether in the fires of Counter-Reformation orthodoxy. The art of the “Braghettone” deserves another look.

Such is the breathtakingly picturesque drama of the Spanish Steps, few visitors to Rome have the mental energy to explore the church that crowns its achievement, the commanding Santa Trinita dei Monti. A worthy award awaits those who make it to the top of its steep staircase however. For inside, in the second chapel on the left, hangs what is possibly the finest example of the Mannerist style in Rome. It’s artist? Daniele Da Volterra.

The subject is the Deposition, the dramatic moment when Christ’s lifeless corpse was taken down from the cross after his crucifixion. Far from the narrative harmonies of Renaissance art and the emotive excesses of the Baroque, Daniele’s work reads like a complex formal puzzle. In a dizzying array of verticals and horizontals, three ladders criss-cross the canvas, supporting an array of figures reaching towards Christ.

Everyone, it seems, wants a piece of the Messiah. One man hangs perilously from the crossbeam of the cross, whilst another gingerly lowers the right arm that he has just cut free from the wood. Two Roman soldiers bear the brunt of the dead weight from below, and an athletic youth swings from yet another ladder, his outstretched hand grasping the dead Christ’s loincloth. In the background an old man descends one more ladder, his day’s work done.

It is a remarkable painting, a hypnotising composition that showcases the very best of Mannerist art in its strange, contorted power. Everywhere is agitation, flux and confusion. Draperies flutter beautifully and improbably in an invisible breeze. There is no landscape here, just a blasted sky and this group of enormous figures dominating an impossibly cramped foreground. Few other paintings in Rome force upon us such a feeling of claustrophobia. In fact, there is probably only one other place in in the city that can invoke a similar response. It’s where “Il Braghettone” got his name – The Sistine Chapel and Michelangelo’s Last Judgement.

It turns out that we are right to see formal the innovations of the old master in Daniele’s masterpiece. For Michelangelo provided the drawings on which the composition was based, as he did for a number of the younger artist’s finest works. Memories live long in the art world, but after 450 years perhaps it’s time we forgave the breeches-maker for his breeches. In the magnificent figures of Santa Trinita dei Monti’s Deposition, we can celebrate an altogether more constructive side of his association with Italian art’s greatest titan.

Visit the Spanish Steps