One of the finest examples of early Christian art and architecture in Rome...

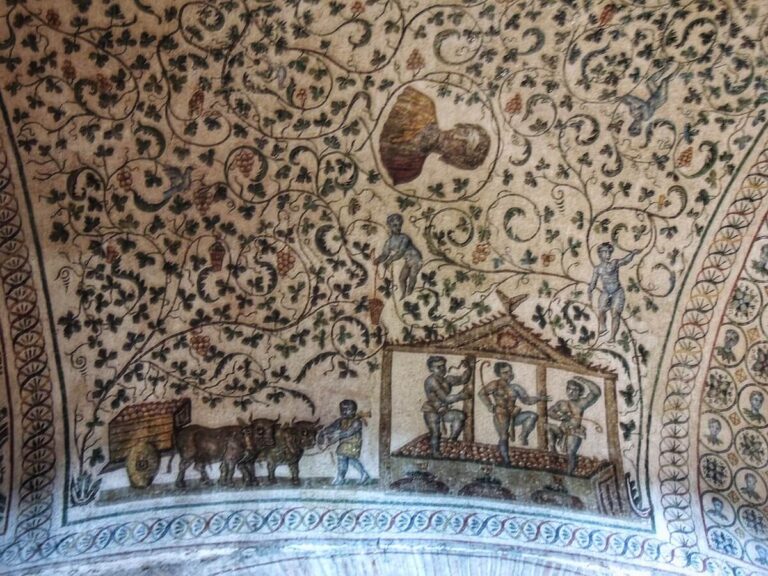

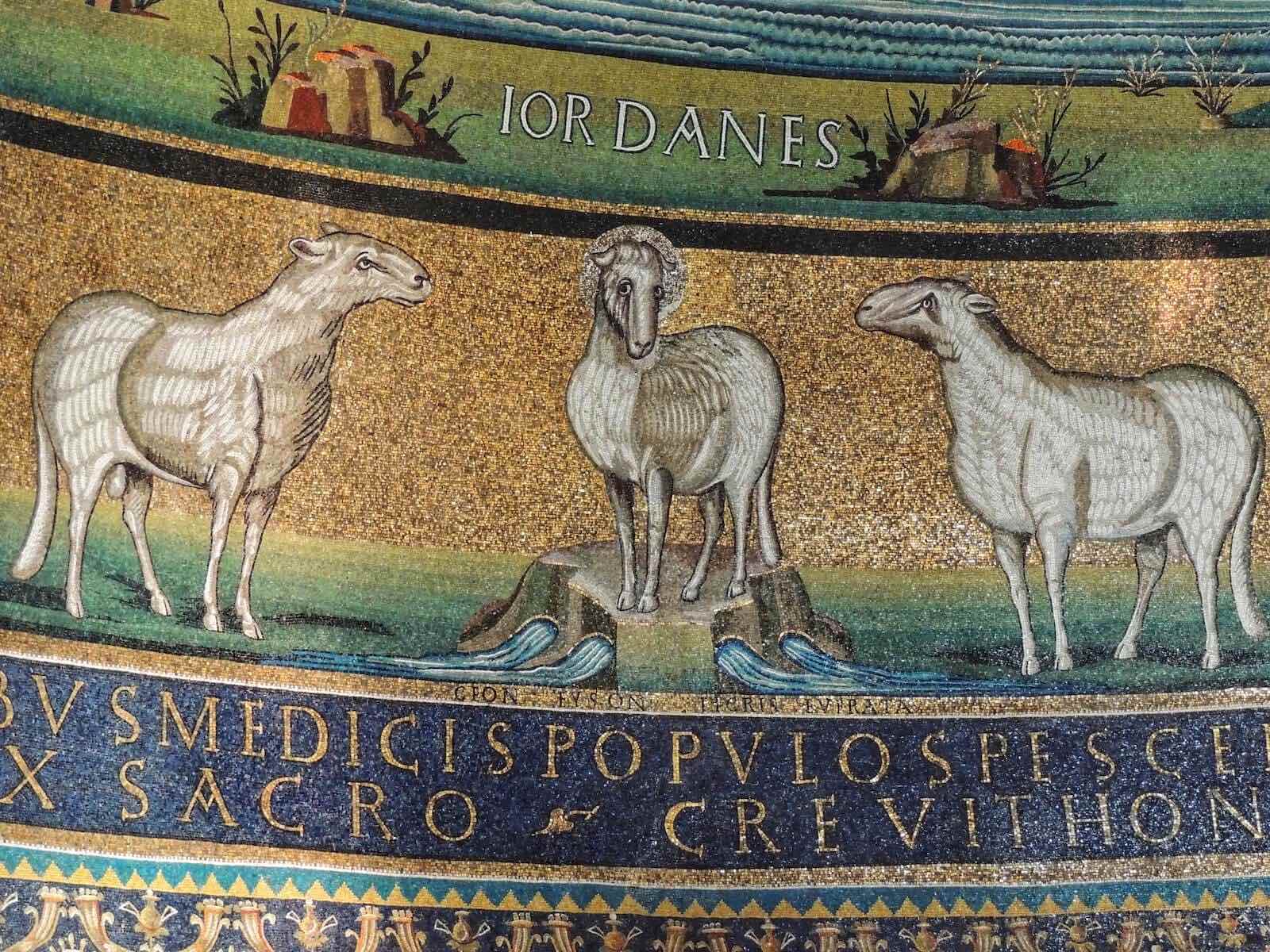

The stunning 4th-century mausoleum of Santa Costanza offers a vivid insight into the Eternal City’s gradual transition from pagan antiquity to Christian capital beginning in the reign of the Emperor Constantine. The vaults of the circular mausoleum are covered with marvellous 4th-century mosaics that are equal parts religious and secular, featuring doves, peacocks and creeping vines. Read on to discover why Santa Costanza is one of our favourite churches in Rome!

Rome Tours

Explore a Hidden Side of the Eternal City

A Tomb Fit for an Empress

Although the church of Santa Costanza owes its current name to a corruption of Constantina, daughter of the Emperor Constantine, the precise circumstances of the mausoleum’s founding are somewhat obscure. Certainly the spectacular edifice did not begin life as a dedicated site of worship: the building’s circular form and location instead mark it out as an Imperial mausoleum, and its consecration as a church can only be dated to the mid 13th century – nearly a millennium after its construction.

In fact, the circular mausoleum originally formed part of a larger funerary complex that included a cemetery basilica and a baptistry, built around the year 326 AD to commemorate Constantina’s recovery from a childhood illness. The basilica, of which only imposing ruins in the green space adjacent to the mausoleum remain, was dedicated to local virgin-martyr saint Agnes, whose intercession reportedly brought on Constantina’s miraculous recovery.

The traditional position that the circular mausoleum, once attached to the larger basilica, was designed as the final resting place for Constantine’s daughter Constantina has recently been revised – many scholars now generally consider the site to have been intended to house the mortal remains of her sister Helena (wife of Julian the Apostate) instead in the 360s, with Constantina originally buried in an earlier, smaller structure on the same site.

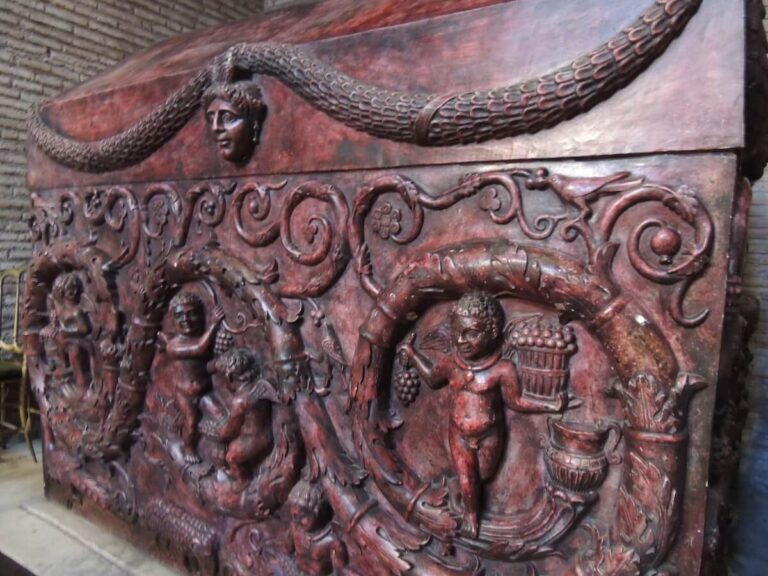

In any case, for centuries two massive purple porphyry sarcophagi graced the interior of the basilica, demonstrating that eventually both sisters were buried here alongside each other. Today you can admire these sarcophagi, fabulously decorated with garlands of vines and putti crushing grapes, in the Vatican Museums and St. Peter’s basilica respectively, whilst replicas have been installed in the mausoleum.

The imperial mausoleum was one of those few buildings that managed to survive the fall of the Roman Empire completely unscathed. At some point during the Middle Ages a legend arose which characterised Constantina as the mythical saint Costanza, apparently a daughter of Costantina. Masses were said in the mausoleum as early as the 9th century, and the building was officially converted into a church dedicated to the apocryphal Costanza in the 13th century by Pope Alexander IV – ensuring its survival in the centuries to come.

The imperial mausoleum was one of those few buildings that managed to survive the fall of the Roman Empire completely unscathed. At some point during the Middle Ages a legend arose which characterised Constantina as the mythical saint Costanza, apparently a daughter of Costantina. Masses were said in the mausoleum as early as the 9th century, and the building was officially converted into a church dedicated to the apocryphal Costanza in the 13th century by Pope Alexander IV – ensuring its survival in the centuries to come.

Innovative Architecture

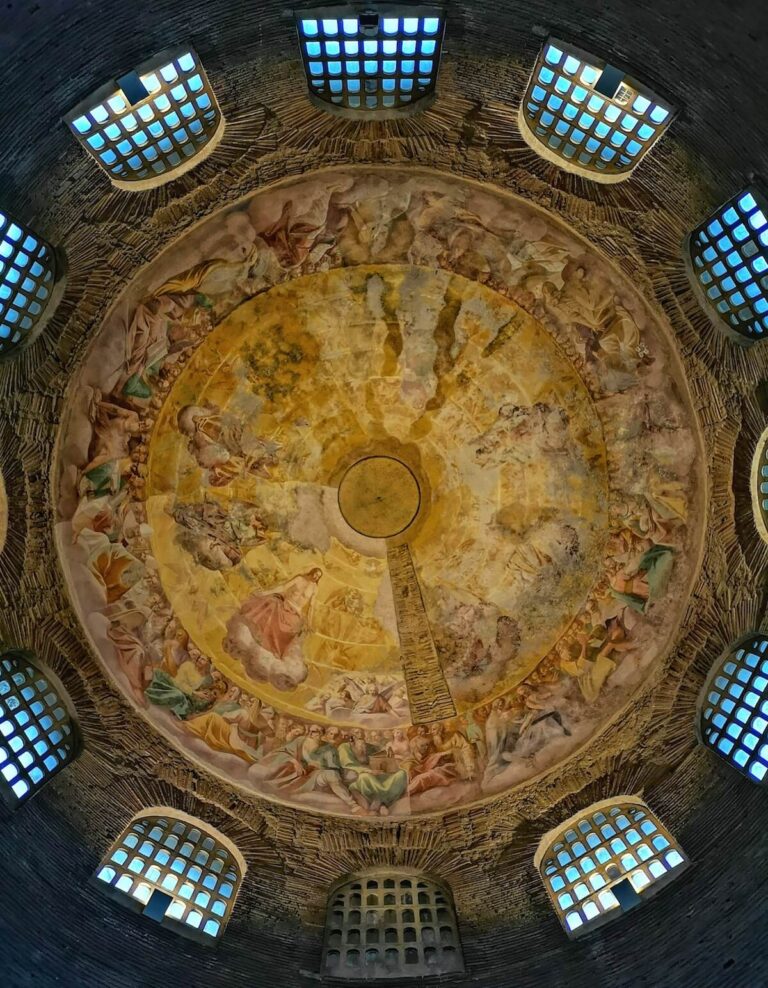

Whatever the exact origins of the Mausoleum, its architecture marks it out as one of the most important buildings of late antiquity. Access to Santa Costanza is via a long avenue flanked by pines on either side leading from the nearby basilica of Sant’Agnese fuori le Mura. The brick mausoleum is one of the earliest examples of a circular Christian building: within, a large central space is surrounded by a circular corridor known as an ambulatory, whilst a dome 19.5 metres high and 22.5 metres in diameter spans the space above.

12 pairs of ancient granite columns recycled from an earlier Roman structure separate the ambulatory from the central area, whilst 12 beautiful mullioned windows flood the mausoleum with light from above. At the centre of the mausoleum stands a Baroque altar.

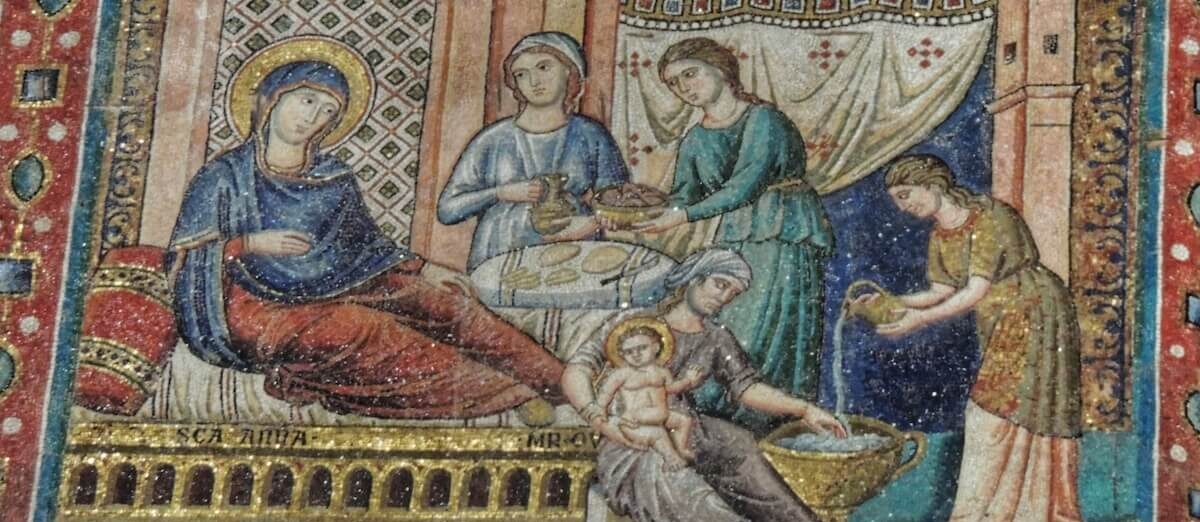

Pagan-Christian Fusion: The Mosaics of Santa Costanza

We don’t know who came up with the idea of rearranging the bones in the Capuchin crypt into the extraordinary shapes and patterns we see today, although various theories have been put forward, including one Father Raffaele from Rome, a highly-regarded Capuchin painter, and the Viennese artist-friar Father Norbert Baumgartmer, a number of whose works can be seen in the adjacent church.

More fancifully, one legend claims that a fugitive artist took refuge in the sanctuary of the Capuchin crypt, and set about organising the bones found down there into elaborate artworks as an act of contrition and recognition of his own sinful nature. Still another tall-tale gives the authorship to a group of Capuchin friars who, escaping the horrors of the guillotine during the Reign of Terror after the French Revolution, whiled away their exile in the macabre task.

Equally magnificent mosaics once adorned the central space, but by the 17th century they had become badly damaged and were falling off. The mosaics were entirely replaced with rather anonymous frescoes depicting the life of Saints Constance, Agnes and Emerentiana.

Luckily for us, Francisco de Holanda produced a series of watercolours depicting the original mosaics in the middle of the 16th century, giving some idea of their lost splendour. Two rows of scenes drawn from the Bible, one from the Old Testament and one from the New Testament, once graced the vault, divided by caryatids and scrolls. Beneath these religious scenes a seascape depicting marine animals of all kinds and putti fishing continued the synthesis of pagan and Christian subject matter typical of Santa Costanza.

Birds of a Feather Flock Together:

The Drunken Antics of the Bentvueghels

For centuries it was widely believed that the Mausoleum was an adapted pagan temple dedicated to Bacchus thanks to the wine-making themes that appear in the mosaics and on the sarcophagi. This traditional, if erroneous, association gave rise to a bizarre custom in the 17th century when a group of rowdy Dutch artists living in Rome known as the Bentvueghels (literally Birds of a Feather) adopted the ancient mausoleum as the location for their initiation rites.

The festivities would often last for a day straight, and concluded with toasting the admission of a new member with a libation in front of the massive porphyry sarcophagus they believed to hold the earthly remains of the bacchanalian god. Pope Clement XI outlawed the tradition in 1720, but a graffitied list of the names of the drunken Dutch painters survives on a wall of the mausoleum.

These days Santa Costanza is a much quieter place, seemingly lost to time in the leafy eastern suburbs of Rome. Tourists rarely venture here, making it one of the great hidden gems of early-Christian art in the city. Make sure to pay a visit next time you come to Rome!

Dive Deeper into Rome