Beyond the iconic masterpieces created by Michelangelo and Raphael for the popes in the Vatican Palaces and Sistine Chapel during the first decade of the 16th century, Rome is not nearly as well-known for its heritage of Renaissance art as Florence – justifiably regarded as the glittering urban jewel of Italy’s Golden Age. But if you know where to look, the Eternal City conceals some magnificent testaments of its own to this magical period when science and artistry joined hands to kick-start a revolution in how people saw the world around them.

One of the absolute highlights of the Roman Renaissance is the Carafa Chapel in the beautiful church of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva just across the road from the Pantheon, where the young Filippino Lippi showed the city’s elites exactly why he was already considered one of the brightest young things on Florence’s art scene even before he had celebrated his 30th birthday.

Best Rome Tours

Explore the Best of Rome

By the 1470s, the Neapolitan cardinal Oliviero Carafa was one of the most powerful men in Rome. After a string of illustrious diplomatic appointments he was awarded the military command of the Papal fleet, where he made his name by orchestrating the sieges of the Turkish cities of Satalia and Smyrna, recapturing them from the formidable maritime forces of the Ottoman empire. Against the cardinal’s wishes, the Italian crusaders razed the city and mounted 215 Ottoman heads on spikes to their ships in brutal warning as they sailed from the site of devastation.

Despite the Pope’s concern at this undiplomatic act of provocation, Carafa was nonetheless ushered back to Rome in January 1473 with a hero’s welcome, and processed through the streets like a conquering ancient Roman general returning from a campaign – at the head of a triumphal procession, he led a parade of 25 flamboyantly attired Turkish prisoners and 8 camels through the city to the very doors of St. Peter’s basilica itself.

The Chapel

Dominicans at Santa Maria Sopra Minerva

With his star fully in the ascendant, over the coming years Carafa directed his thoughts towards posterity, and set about creating for himself a magnificent funerary chapel that would house his mortal remains and ensure his reputation as one of the era’s leading lights for centuries to come. The cardinal was a devoted member of the Dominican order, whose Roman base of operations was the imposing medieval basilica of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva. And so it was only natural that it was here that Carafa chose to make his mark, purchasing a primo piece of real estate in the church’s right transept, not far from the high altar.

And make his mark he certainly did. Inspired by the great commissions being undertaken by powerful patrons aiming to exalt their status and show off their munificence all across Florence, Carafa hired the prodigiously talented Florentine painter Filippino Lippi to create his eternal testament in paint between 1488 and 1493.

The Painter

The Precocious Son of a Wavering Friar

When it came to Filippino, paint ran in his very veins. The handsome young artisan was the fantastically gifted son of Filippo Lippi, himself one of Florence’s most famous painters and an unconventional (to say the least) Carmelite friar. Beyond his facility with a paintbrush, the elder Filippo was something of a libertine.

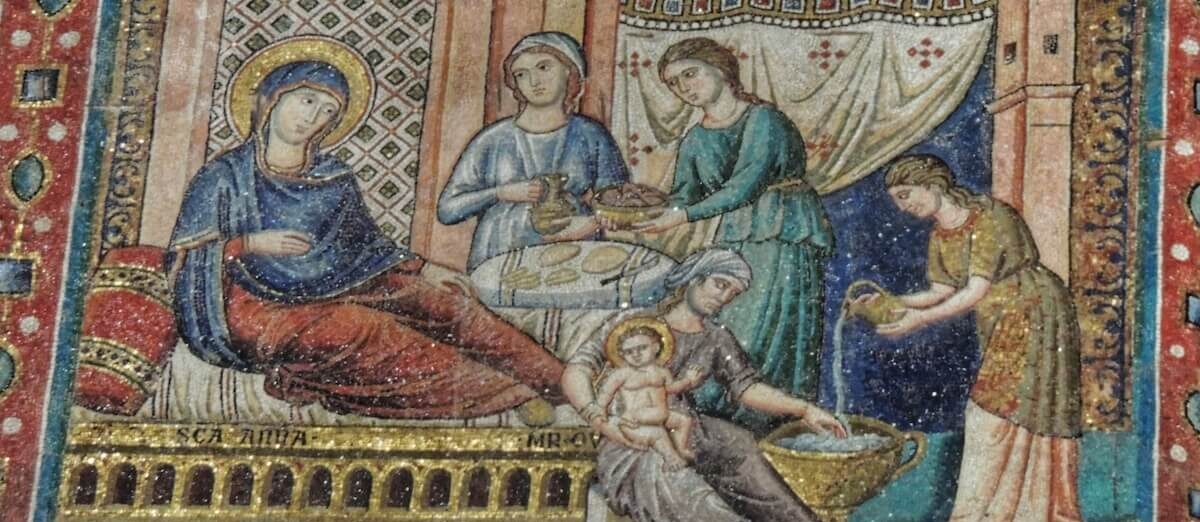

Unconcerned with his inviolable vows of chastity, Filippo cheerfully led a life of the flesh after eschewing the confines of his monastery’s walls. His escapades culminated when he fathered little Filippino with his lover Lucrezia Buti, a nun whom he had scandalously seduced under the pretext of requiring a suitable model for an altarpiece was painting of the Virgin Mary. After the wayward friar’s death in 1469 (poisoned, according to dubious legend, by Lucrezia’s disgruntled relatives in revenge for corrupting the nun), young Filippino took up the family business and quickly made his name working alongside Botticelli as his most valued apprentice.

After a string of high profile commissions that included completing the Brancacci Chapel in Florence, the Medici prince Lorenzo the Magnificent invited the young painter to participate in the decorations for his villa at Spedaletto in the Tuscan countryside. So impressed was he by Filippino’s talent that Lorenzo, hoping to curry favour with the powerful cardinal, recommended the painter to Carafa when he heard that he was looking for someone to decorate his Roman chapel.

And so Filippino interrupted the work he had just begun in what would become another of his masterpieces, the Strozzi chapel in the Florentine church of Santa Maria Novella, packed his bags and set out for the Papal capital with a big reputation to uphold. Carafa’s faith was not misplaced: when the chapel was opened on the Feast of the Annunciation in 1493, it caused a sensation. The Borgia Pope Alexander VI himself was present at the ceremony, and it was immediately clear that Lippi had set a new standard in the Eternal City with his virtuoso combination of ideas drawn from the ancient world and the most cutting-edge techniques of 15th-century visual art practice – the Florentine Renaissance had come to Rome.

The Commission

The Mother of God and a Heretic-Busting Doctor

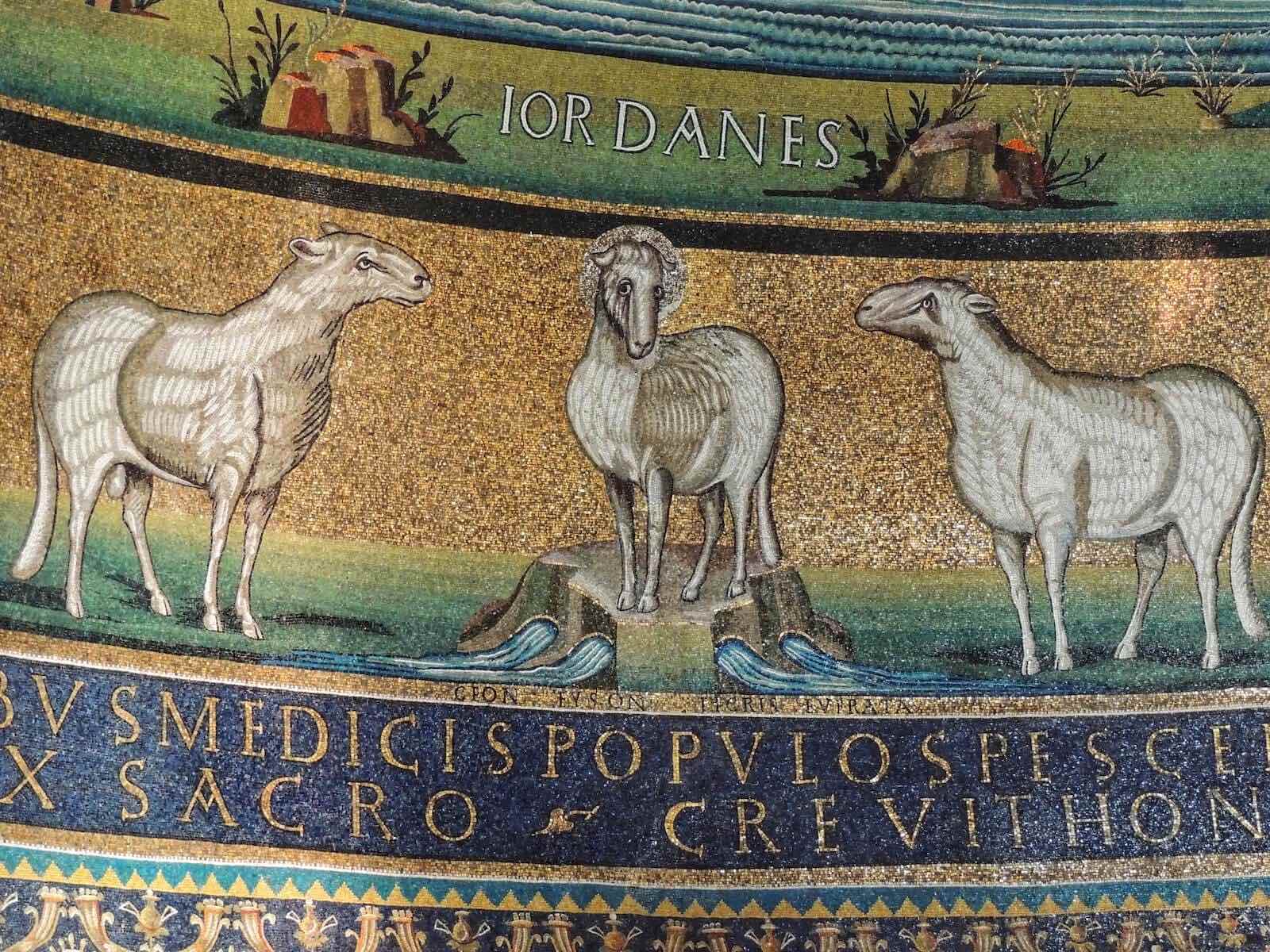

In addition to exalting his own achievements, Carafa’s chapel was to be dedicated to two figures of particular importance to the Dominicans – the Virgin Mary and St. Thomas Aquinas, the rigorously upright medieval theologian and doctor of the church who was the Order’s patron saint. Accordingly the walls are painted with scenes devoted to this duo – on the main altar wall Lippi depicted two central scenes from the life of the Virgin, the Annunciation and the Assumption.

On the right-hand wall meanwhile, Aquinas’ devotion to orthodox learning and tireless fight to stamp out heresy are given pride of place. In The Dispute of Saint Thomas the theologian refutes the learning of heretic philosophers and piles up their works for consumption in the Inquisition’s fires, whilst in The Miracle of the Book a statue of the Crucified Christ comes alive to praise Thomas for his heretic-busting tomes.

In the ceiling vault above, meanwhile, are the four ancient sibyls who according to Christian tradition predicted the coming of Christ in their prophecies. Their dynamic bodies seem to twist and writhe on the ceiling in a state of permanent agitation, surrounded by fluttering scrolls and books that symbolise their preternatural knowledge.

The sibyls became a popular motif in the Renaissance as a way of linking the classical and Christian worlds – look for Michelangelo and Raphael’s contrasting interpretations of these venerable seers in the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel and Santa Maria della Pace’s Chigi chapel respectively.

Start Spreading the News

The Annunciation

The main altar wall of the chapel immediately showcases Lippi’s unique painterly skills, engaging in some nifty visual gymnastics. At its centre is a representation of the Annunciation that looks like it’s a stand-alone altarpiece, but is actually part of the wider frescoed surface cordoned off with a fake frame made of stucco. The annunciation was the moment when the archangel Gabriel delivered God’s message to the Virgin Mary that she had been chosen to give birth to the Messiah.

The natural drama of the scene made it a favourite Renaissance subject, and Lippi’s strikingly beautiful Mary vividly recalls the greatest works of his Florentine master Sandro Botticelli. As the winged angel delivers his message on bended knee clutching the lily that symbolises Mary’s purity, the Holy Spirit swoops into the scene on the left in a magically painted gust of wind.

Rather presumptuously, the event takes place not in the surroundings of an ancient Nazarene dwelling as the Bible dictates, but instead in the book-lined study of a learned Renaissance scholar – the study, of course, of Carafa himself! Some subtle details give the game away. The cardinal’s distinctive red and white striped insignia appears both carried aloft by putti on the illusionistic pilasters that frame the scene and on the ceiling in the room’s background, which also features a beautifully painted glass carafe holding an olive branch on the shelf behind the Virgin – a visual pun that for contemporaries would have drawn attention to the patron’s full name, Olivarius Carafa.

Carafa himself makes an appearance in the scene, kneeling in reverence at the understandably preoccupied Virgin’s feet as a sober Thomas Aquinas makes the introductions with a reassuring arm around the cardinal’s shoulder.

DID YOU KNOW? THE STORY OF GROTTESCHI

Make sure to examine the stucco frame dividing this scene from the rest of the paintings on this wall, as well as the illusionistic painted pillars in the Cardinal’s study – the sinuous decorations of plants and masks are testament to an incredible event that took place whilst Lippi was in Rome that would have a profound effect on his career – the discovery of the ancient emperor Nero’s Golden House (Domus Aurea) underneath a Roman vineyard nearly 1,500 years after its abandonment when Nero was assassinated in 68 AD. Lippi was one of the first to descend into the opulent rooms still covered with magnificent classical artworks, and he was quick to adopt the style of ornamentation known as grotteschi that he found there in his own artistic practice.

Learn about the grotteschi in Nero’s Golden House here.

The Assumption

Mary’s Fast-Track to Heaven

On the wall above the Annunciation, Lippi painted another key moment in the life of the Virgin – this is the Assumption, when according to Catholic doctrine Mary’s body and soul were carried straight to heaven by angels shortly after she finished her time on earth. Mary, seemingly not a day older or any less beautiful than she was in the Annunciation despite the passing of the decades, treads over the clouds with a feather-light step as she ascends towards the chapel’s ceiling and out of our terrestrial vision. All around her incredibly animated angels swoop, float and dive as they herald the mother of God’s journey into the skies to join her son.

As supernatural beings they seem to be unbound by the petty limitations of gravity or the laws of physics, tripping easily through the aether. Each plays a different musical instrument, and it seems that they’re making one hell of a racket – one batter a drum looped around its waist, whilst a companion rattles a tambourine; others bow at elaborate stringed instruments and blow into massive trumpets.

The angel just to Mary’s right meanwhile operates a full-on Renaissance bagpipe decked out in Carafa’s distinctive colours of red and white. The whole ensemble marks a vitally important landmark in the evolution of technique in Italian Renaissance art: Lippi successfully adopted a complex perspectival trick known as sotto in su, or ‘from below,’ which enabled figures painted high up on walls to illusionistically appear as if they were looming right above the viewer, dissolving the wall and opening up a view into the heavens.

Surrounding the framed image of the Annunciation, Christ’s apostles reflect the actions of the viewers in the chapel by raising their eyes towards the amazing apparition in the sky above. Take the time to examine the landscape the disciples find themselves in, because Lippi included some fantastic exotic details here. Horsemen ride towards imposing castles on rocky crags on the left, whilst on the right a great procession of men in Turkish garb on horses and mules snake through the countryside as they depart from a city.

At the head of the procession a man leads a lion, and behind him an elaborately turbaned character battles to control the unmistakable figure of a giraffe. Lippi is obviously paying tribute to Carafa’s role in the Turkish raids, immortalising the exotic Ottomans beating their hasty retreat. The sight of the giraffe must have been particularly fascinating for Roman viewers – Lippi’s Florentine patron Lorenzo the Magnificent had recently acquired one, and the artist wasted no time in integrating the exotic animal into his pictorial schema.

Aquinas and the Heretics

The right wall of the chapel represents a much darker theme, but one that was very dear to the Dominicans – the contemporary fight against heresy. Though in reality named after Saint Dominic, the order was jokingly referred to as the domini canes, or the hounds of the Lord, for good reason: they were the driving force of the Inquisition responsible for ceaselessly persecuting voices of dissent or those promoting unorthodox positions on questions of faith or the nature of the world during the early-modern period.

The ultra-orthodox 13th-century theologian Thomas Aquinas was their natural patron, and here the portly friar is seated on an elaborate throne holding a book featuring the foreboding words of St. Paul, Sapientiam sapientum perdam – ‘I will destroy the wisdom of the wise.’ Decorating the throne are further signs of authoritarian sympathies: the bundles of sticks bound together on the columns, known as fasces, were symbol of the Roman legions and adopted by Mussolini in the 20th century as the icon of his illiberal fascist movement.

Lying prostrate at Aquinas’ feet is a scowling old man meant to personify evil: some scholars identify him as the Arabic philosopher Averroes, and he is being gawped at by personifications of medieval learning – Theology, Philosophy, Dialectic and Grammar, the last of whom brandishes a cane ready to punish the unstudious.

In the left foreground Lippi brought to life a brilliantly painted rogues gallery of heretic thinkers, promoters of apparently false doctrines put in their place by Aquinas’ incomparable intellect. The sombre and bearded Arius wreathed in a yellow cloak on the left seems utterly dismayed because his Arian heresy, which suggested that Christ was inferior to God the Father, has been refuted by the judging Aquinas.

To the right the sharply-featured and distinctly Roman-looking Sabellius sadly bows his head – his heretical belief that Christ and God were exactly the same has similarly been condemned. Cloaked in a fur cape and hood in the crowd to the right is Mani, who founded the dualist philosophy of Manichaeism, holding a finger to his lips.

Scattered on the ground all around them are open books and sheaves of parchment, the forbidden writings of the philosophers destined to go up in flames on the Inquisition’s pitiless fires. Peer into the background to the left of the throne for a fascinating view of contemporary Rome: seemingly galloping into view is the ancient equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, which today occupies pride of place atop the Capitoline Hill. But it was only moved there when Michelangelo redesigned the piazza in the 1540s, and in Lippi’s time the sculpture stood before the basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano, where it was thought to represent the Christian emperor Constantine.

How to Get There

Santa Maria Sopra Minerva is located just a few yards from the Pantheon. Stand in front of the Pantheon facing its façade, and walk around it on the left-hand side, keeping the temple to your right. You’ll know you’ve come to the right place when you reach the piazza outside the church, still in full view of the back of the Pantheon – an incredible marble elephant, designed by none other than Bernini himself will be greeting you with swaying trunk as he supports an Egyptian obelisk in the centre of the square!

The Carafa chapel in Santa Maria Sopra Minerva is one of the undisputed highlights of Renaissance art in Rome, right up there with the works of Raphael and Michelangelo at the Vatican. But it’s surprisingly unloved by tourists to the Eternal City, and chances are you won’t have many people for company in the spectacular Gothic basilica. So when you’re heading to the Pantheon, make sure to make a quick pit-stop at Santa Maria Sopra Minerva to admire one of Rome’s finest artworks. Best of all? It’s totally free!

Book Your Rome Experience