It was on the steps of St. Peter’s itself that the Swiss Guard made their valiant last stand. No match for the ferocious German Landsknechts rampaging through the city, the Pope’s elite personal troops attempted a final rearguard in the Vatican’s Teutonic cemetery. Hopelessly outnumbered, they retreated towards the massive basilica, whose ongoing reconstruction was the pride and joy of the Catholic world. But the symbolic might of that awe-inspiring sight proved illusory: supposedly mighty Rome had feet of clay, and the Swiss Guard were cut down almost to a man.

Best Vatican Tours

Follow in the Footsteps of Popes and Saints

The year 1527 still lives in infamy in the annals of Roman history. On the fifth of May, the vast and unruly army of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V arrived at the gates of Rome. Threatening to mutiny over unpaid wages after an exhausting series of military campaigns, the army was determined to sack the city and take whatever they could get their hands on in loot.

Despite the unshakeable faith of reigning Pope Clement VII in his plucky but paltry Swiss Guard and the 5,000 militia commanded by the mercenary general Renzo da Ceri, the city was woefully unprepared for a full-scale military offensive.

The assault was brutal and swift: 8,000 citizens were slaughtered on that first day, and by the time the orgy of bloodletting finally ceased fully 23,000 of Rome’s already meagre population of 55,000 lay dead in its streets. The infirm of the hospital of Santo Spirito were slaughtered in their beds, whilst the young residents of the city’s orphanage were thrown screaming into the Tiber. ‘The stench,’ according to one visitor, ‘was terrible.’ As another eyewitness would later recount in his diary, ‘hell itself was a more beautiful sight to behold’ than the city in those blood-soaked days.

Principal amongst the marauding troops were the fearsome Lutheran mercenaries known as the Landsknechts, who saw an opportunity to demonstrate once and for all that the secular power of the Roman church was an illusion, and that its golden age had long passed. They carried out their task with a grim sectarianism and unmatched ferocity: monks were tortured, nuns were raped, and priests were forced to participate in travestied parodies of the mass.

Dressed in pilfered vestments, the soldiers conducted mock papal conclaves in which they elected Martin Luther or even themselves to the seat of St. Peter. One landsknecht reportedly snatched the spear with which Christ’s side was pierced on Calvary from its altar in St. Peter’s, and rode through the Borgo holding it aloft before him.

Money and money alone could save your life: one wealthy prelate was lowered alive into a tomb in the church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli and only released when he agreed to pay up, whilst Cardinal Ferdinando Ponzetti was dragged through the streets at the end of a rope until a ransom was delivered. The unfortunate cardinal nonetheless died of his injuries, and was buried in the magnificent chapel that he had commissioned from painter Baldassare Peruzzi a decade before.

Many of the artists who had helped to transform Rome into one of the great triumphs of the Italian Renaissance over the preceding decades also got caught up in the mayhem. Peruzzi himself was captured by the invading forces and only released when his native city of Siena payed a ransom; the same happened to Perino del Vaga, the Mannerist painter who would go on to paint a fabulous series of frescoes in the papal apartments in Castel Sant’Angelo.

Others, such as Parmigianino and Rosso Fiorentino both fled the city never to return. Sebastiano del Piombo would later write to his friend Michelangelo that he never fully recovered from the horrors he had seen during the Sack.\

The exception was the irrepressible sculptor Benvenuto Ceillini, who seemed to have enjoyed the chaos immensely. Working as a cannoneer on the ramparts of Castel Sant’Angelo alongside fellow painters Lorenzo Lotto and Raffaello di Montelupo, in his autobiography Cellini boasts of his unerring marksmanship, picking off enemy soldiers and generals at will. Rapt by the spectacle of violence, Cellini described how ‘my drawing, my wonderful studies, and my lovely music were all forgotten in the music of the guns.’

The Pope was himself lucky to escape the mayhem with his life. Seeing that the jig was up at the annihilation of the Swiss Guards, Clement frantically made his way to the entrance of the Passetto del Borgo, an 800-metre long fortified corridor that leads directly from the Vatican Palaces to the Bastion of Saint Mark in the impregnable fortress of Castel Sant’Angelo overlooking the river Tiber.

As the Pope scurried along the narrow passage, his surviving hangers-on covered him with a dark coat in order to ensure that his gleaming papal vestments wouldn’t attract the attention of the besieging army’s gunmen. Today you can still see the scars of the arquebus volleys that peppered the walls of the Passetto as the Pope beat his desperate retreat.

But the imposing fortifications did their job: Clement reached the safety of Castel Sant’Angelo unscathed, where he spent the next six months as a virtual prisoner in the luxurious apartments that had been recently installed in the upper floors of the one-time Mausoleum of Hadrian, an impregnable mini-city immune to the ravages of the soldiers below.

Although Clement’s audacious flight from the pitiless blades of the Landesknechts was no doubt the most famous usage of this secret escape route, the Passetto di Borgo has a much longer history. Known in Roman dialect simply as “Er Corridore,” the passetto originally formed part of a defensive structure built by the barbarian general Totila in the year 547 AD in order to defend the army camp he set up here after his Gothic hordes sacked the city.

Pope Leo IV transformed the structure into a city wall in the 9th century in order to protect the Vatican from Saracen raiders, before the fortified covered walkway that we see today was probably constructed during the papacy of Nicholas III around the year 1277 as part of his campaign to move the Papal residence from the Lateran to the Vatican.

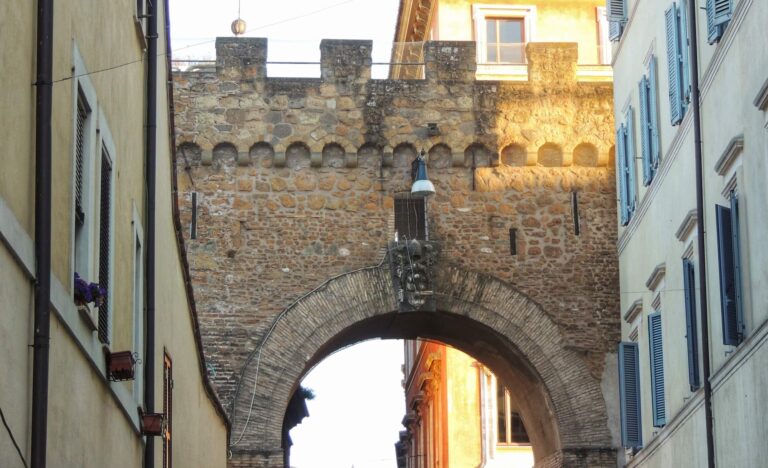

The Passetto is immured in the bustling neighbourhood known as the Borgo, a dense network of streets that materialised in the shadow of the Vatican city during the Middle Ages full of taverns, hostelries and artisan workshops that sprang up to service the needs of the denizens of the Vatican and the legions of pilgrims who flocked there every year. Cutting through this medieval maze in an arrow straight line from the Vatican, the imposing brick fortification was ideally suited to surveilling the the surrounding countryside, providing advance warning of any incoming military threats or civil unrest.

As the area around the Vatican increased in strategic importance a series of popes renovated and fortified the passageway, amongst them the Renaissance pontiffs Nicholas V, Sixtus V and the Borgia pope Alexander VI, who added a series of towers – an inscription on one reads “ALEXANDER PP VI ANNO MCCCCLXXXXIII.’

Alexander’s foresight in reinforcing the passetto was soon made apparent when the troops of the French King Charles VIII briefly invaded Rome in 1494, forcing Borgia to seek refuge in Castel Sant’Angelo. According to legend, the notorious pope also made use of the secret passage for more nefarious purposes, secretly leaving the Vatican palaces via this route to carry out clandestine trysts with an array of lovers.

But it was the desperate flight of Clement VII from the brutal German mercenaries during the dark days of the Sack of Rome that remains the Passetto del Borgo’s most famous hour. In the centuries to come the Passetto would lose its strategic significance, and Clement was the last Pope forced to make use of it in times of crisis.

Even today it stands as a fascinating reminder of one of the most traumatic crises in the long story of Rome; close your eyes and you can almost still hear the clicking of the Pope’s heels as he rushed panic-stricken towards Castel Sant’Angelo nearly 500 years ago.

Book Your Vatican Experience