Gasp, gush, it’s my body, yes my body that gasps, foams, burns. All I can sense is spasm, all I can feel is pain. But it lasts a moment, it lasts only a moment. It’s all over. It went as it had to, as I would have wanted it not to. I look at myself as if from a distance, the open wounds still spurting blood, but it’s okay like this. I’ve always lived like this, in a red, red sea of blood.

- Gabriele Tinti, The Boxer (Part 1)

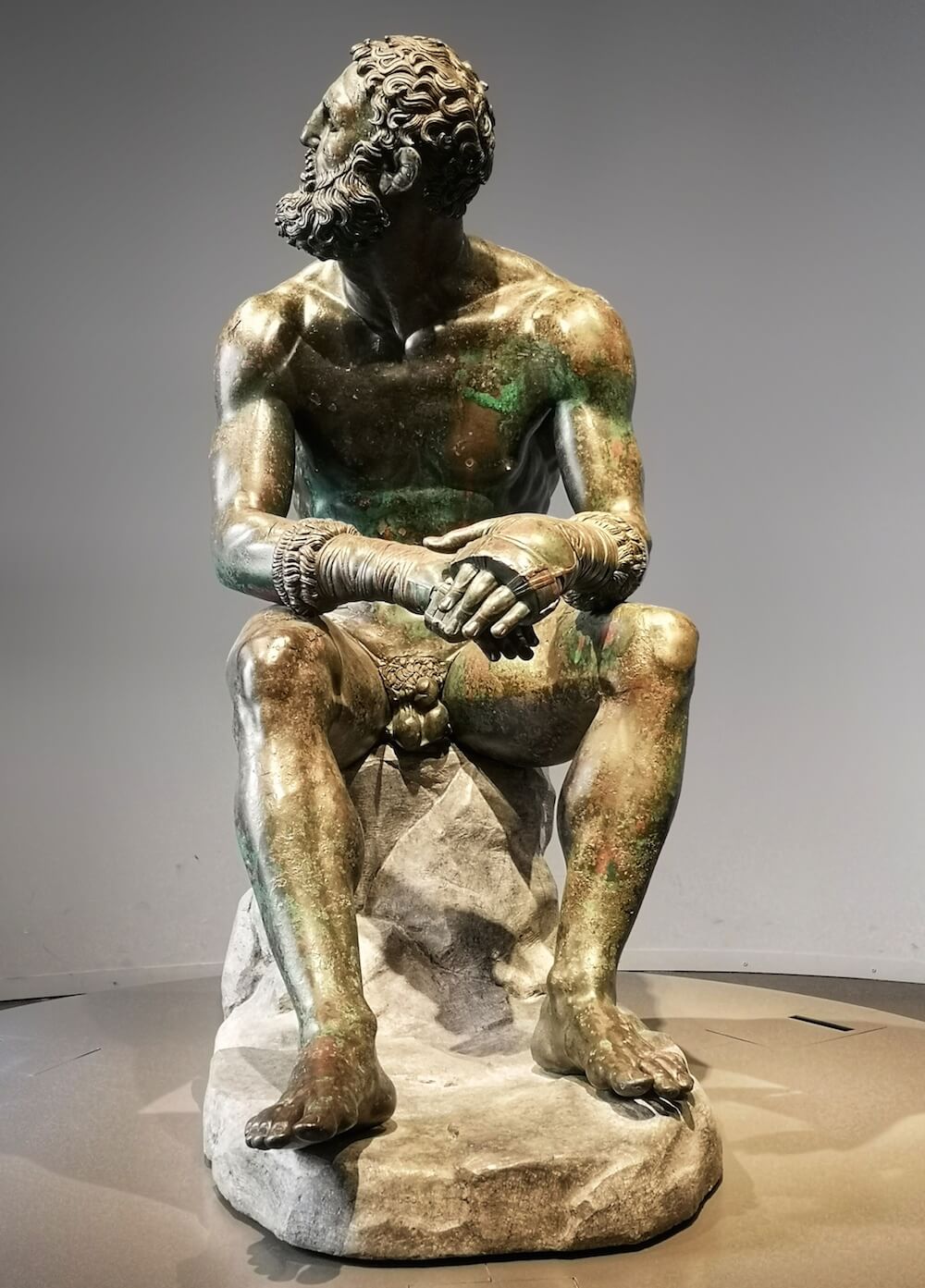

Bruised but unbowed, the boxer is finally at rest, wreathed in a pensive calm as he sits hunched over with his arms resting heavily on his knees, lost in thought. But the brutality that the ageing fighter has just gone through is etched into every feature of his weary haunted face and battered body. This ancient Hellenistic bronze is surely one of the most powerful portrayals of both the fragility and extraordinary resilience of the human spirit ever carved, an absolute masterpiece of classical art.

The details are incredible - the rippling muscles sculpted with virtuoso verisimilitude are the natural tools of his trade, whilst the nasty looking bruises picked out in deliberate purple discolourations of the metal are the profession's grim consequences. Ancient pugilism was a nasty business - the leather straps wrapped around their hands were the only protection the boxers had, and the tough oxhide could lacerate an opponent's flesh with every blow.

Today the Boxer at Rest is possibly the highlight of the magnificent ancient sculpture collection of the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, part of the National Museum of Rome. Despite boasting a dizzying array of masterpieces from the ancient world, the museum is not well known to tourists. In an attempt to bring this wonderful collection the attention it deserves, we’ve launched a Virtual Tour of the Palazzo Massimo alongside the other collections of the Museo Nazionale. For a taster of what’s in store, this week in our blog we’re taking a closer look at what might just be our favourite classical artwork of all: Il Pugile in riposo, or The Boxer at Rest.

As soon as you enter the room where the ancient pugilist now resides and take in his imposing yet vulnerable form, you realise that you are in the presence of something special. A Hellenistic masterpiece of unknown authorship, scholars estimate that the The Boxer at Rest was created sometime between the 4th and 2nd century BC, and is one of the very few intact bronzes surviving from this period.

What makes the sculpture such a rare survival is the material from which it is made. A precious substance with many uses far more practical than sculpture, bronze was simple to melt down for reuse as cannons, building material and everyday objects. This was the ignominious fate that awaited almost all of the masterpieces of bronze sculpture produced in the Greek world, most of whose finest works we now know only through more durable Roman marble copies. But not the Boxer. He’s the real deal. And his presence is magnetic.

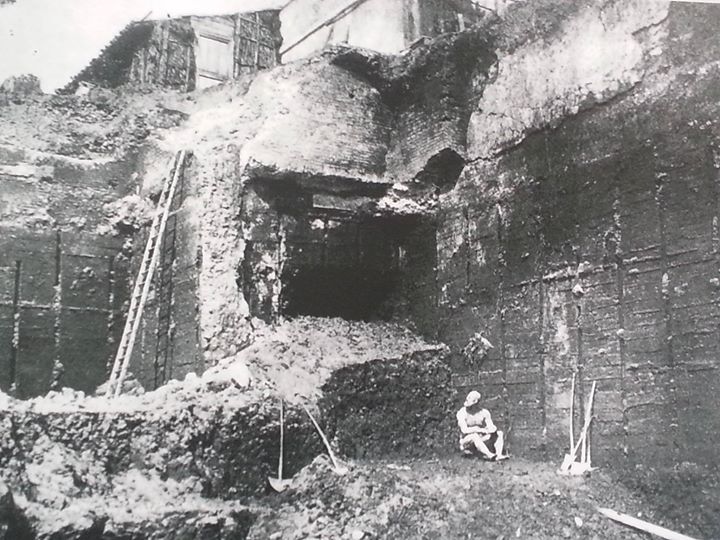

No less extraordinary than the sculpture itself is the story of its rediscovery, not much more than a century ago. The Boxer was discovered in the foundations of an ancient building on Rome’s Quirinal Hill in 1885, during excavations being carried out for the construction of the now destroyed National Theatre. Incredibly intact in its millennial hiding place deep beneath the city, the find took place near the site of the ancient baths of Constantine where it was conceivably once on display as a paean to male athleticism, brought to Rome from its native Greece as a spoil of war.

The sculpture was an object of reverence in late antiquity, attested to by the fact that the boxer’s extremities have been worn smooth from the caresses by ancient admirers - much like Christian statues in the centuries that were to follow, it’s possible that the Boxer was thought to have apotropaic powers, explaining too the fact that it was buried with such care to protect it from looting as the Roman Empire entered its death spiral - the Boxer was discovered not lying in the earth, or scattered in pieces like so many ancient finds, but rather nobly seated on the capital of a Doric column, covered in a layer of sifted earth that protected the delicate surface of the bronze from the ravages of time.

Looking at photographs of its return to the light of day after so many centuries, it is easy to understand the awed excitement of those present at the find. In an evocative account, supervising archaeologist Rodolfo Lanciani describes how even after a long career excavating incredible masterpieces he had

never felt such an extraordinary impression as that created by the sight of this magnificent specimen of a semi-barbarian athlete, slowly emerging from the earth as if awakening from a long slumber after all his valiant bouts.

The archaeologist’s sensation that he was somehow disturbing the centuries-long reverie of the athlete seems a particularly apt response to the sculpture. Even today in the halls of the Palazzo Massimo it’s as if we have disturbed the visibly exhausted boxer’s precious repose - a peek into his dressing room perhaps, the wearily hunched athlete jerking his head up in irritation at our intrusion. We are led to wonder whether the ageing boxer has just fought his final fight, raging against the dying of the light and the inevitable march of time for the very last time.

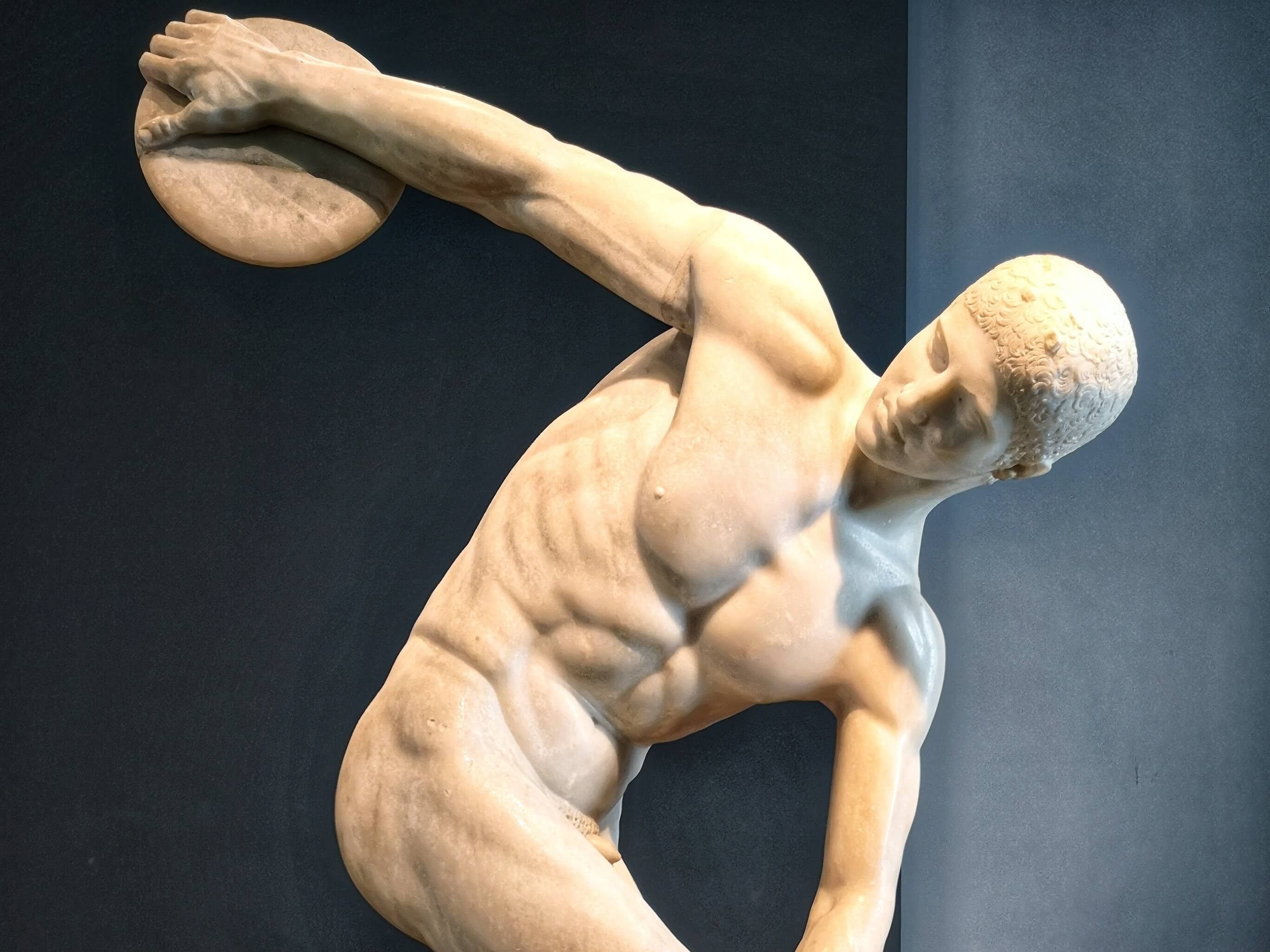

What is it that makes the Boxer such a magnetic presence? Depictions of athletes and their triumphs were hardly rare in antiquity - the restrained power of the Discus Thrower, a wonderful version of which you can see elsewhere in the Palazzo Massimo, or the Herculaneum Runners now in the Naples Archaeological Museum paint a rich picture of athletic elitism, of virtuous bodies reflecting virtuous souls.

Far from the rarefied idealism that confers such a superhuman quality to those paragons of classical art, however, the brute realism of the Boxer is quite simply startling - a work of probing psychological insight drawn from the world of men rather than the realm of gods. What we are looking at is not the perfected archetype of a generic ancient athlete - no, such is the pulsating individualism of the figure that we’re surely gazing at a portrait of a real boxer, living and breathing still across the gulf of the centuries thanks to the virtuosity of the ancient sculptor’s art.

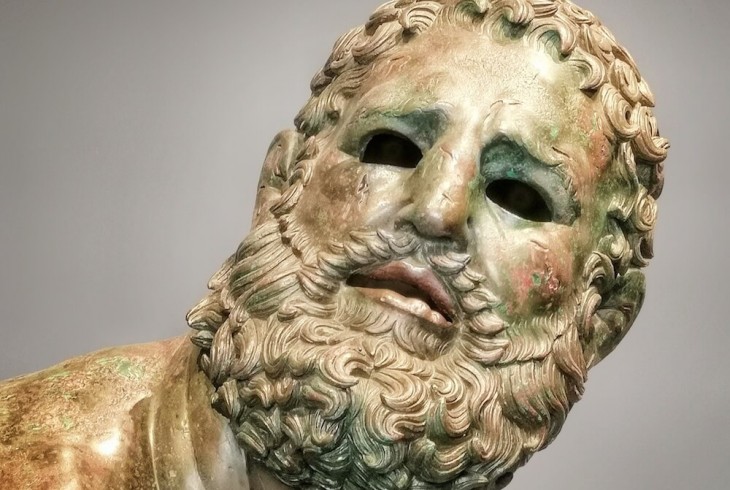

Muscular still, our boxer is no longer in the first flush of youth, and his body is beginning to show the signs of a life spent in the unforgiving world of the ancient ring. Looking closely, an extraordinary wealth of physiognomic details make clear that this was no mere pretty boy. His crooked nose bears all the marks of a fracture badly set, or even a nose freshly broken in this most recent bout; his puffy and swollen eyes betray a lifetime of being smashed in the face, while the boxer’s bloodied cauliflower ears, a disfigurement we’re more used to these days in rugby players, were something of a calling card for practitioners of combat sports in the ancient world - although the early Christian writer Tertullian preferred the appellation aurium fungi, or ‘mushroom ears.’

Even the sculptor’s choice of materials plays its part in bringing the immediacy of the pugilist’s brutal art to bear: livid bruises stand out on the athlete’s skin, blotches of red amongst the mottled green-brown bronze offering testament to the ferocity of the fighting. To achieve these wonderfully vivid details, the sculptor added red copper inlays to the cast bronze in order to bring the multiply wounded and scarred boxer’s body to life.

We can learn a lot too about the practices of ancient boxing from this incredible sculpture. The fighter’s manly member is discreetly tied away, infibulated by means of a kynodesmē or ‘dog tie,’ a strip of leather that ensured the boxer’s penis wouldn’t flap about indecorously during the contest. Of course, the kynodesmē wasn’t only aimed at decorum - as the pugilists conducted their bouts in the nude, it also protected the combatants from painful low blows.

The only other article of clothing interrupting the Boxer’s nudity are his thick leather gloves, the caestus, a recent invention in the boxing world in the 4th century AD that were as apt to bludgeon the face of your adversary as they were to protect your own hands, the blows rendered even more fearsome by the metal studs holding the gloves together.

And so, was our boxer victorious in his final tussle, or did his career end in bitter defeat? Some have seen in the sculpture the inspiring figure of Mys of Taranto, a 4th-century BC boxer whose career comprised a series of devastating losses before improbably triumphing at the Olympic Games in his final bout. But here there is no sense of celebration in the culmination of a lifelong dream. Here is none of the triumphal exultation of Muhammed Ali as he stands over the vanquished Sonny Liston in what is perhaps the greatest photographic rendering of boxing’s brutal artistry. Is, then, the enigmatic expression of our bronze boxer instead one of dejection, the pained grimace of the vanquished? I’m not so sure.

Ultimately, neither the identity of the athlete or the outcome of the just concluded bout seem to matter: in the moments after the fight the Boxer has already turned his thoughts towards higher things, where winning and losing are merely two sides of the same coin. No, although our bronze is surely one of the finest evocations of a sportsman in the story of art, this is an image that transcends the world of the ring entirely.

The Boxer’s vacant eye sockets only increase the sensation that the battered pugilist is staring beyond, contemplating the vagaries of his violent life - although here we’re slipping into an ahistorical romanticism: originally the boxer’s eyes would have been rendered in coloured glass or stone, shining out brightly from his battered visage.

For a work of such startling poetic power, marrying beauty and unflinching brutality with a mastery like few other works in the story of art, it seems fitting to end where we began, with the words of a poet. In his ekphrastic meditation on the Boxer at Rest, Gabriele Tinti vividly captures both the juddering force of those raining blows of caestus-wrapped fists as well as the psychological drama playing out in the pugilist’s psyche:

He hits me in the face/ A rush goes through me / pure unstemmed pain / I touch myself, the wound is open / it spurts blood, but it’s nothing/ everything’s good / it’s only blood.

I look at myself and see myself a distance / and everything is splendour in the place I am /everything is calm and rapture and pleasure / Everything is love / I look at myself and see a man /just a man.

To learn more about this absolute masterpiece of ancient Greek sculpture as well as the remained of Palazzo Massimo’s peerless collection, be sure to check out our Museo Nazionale Romano virtual tour!