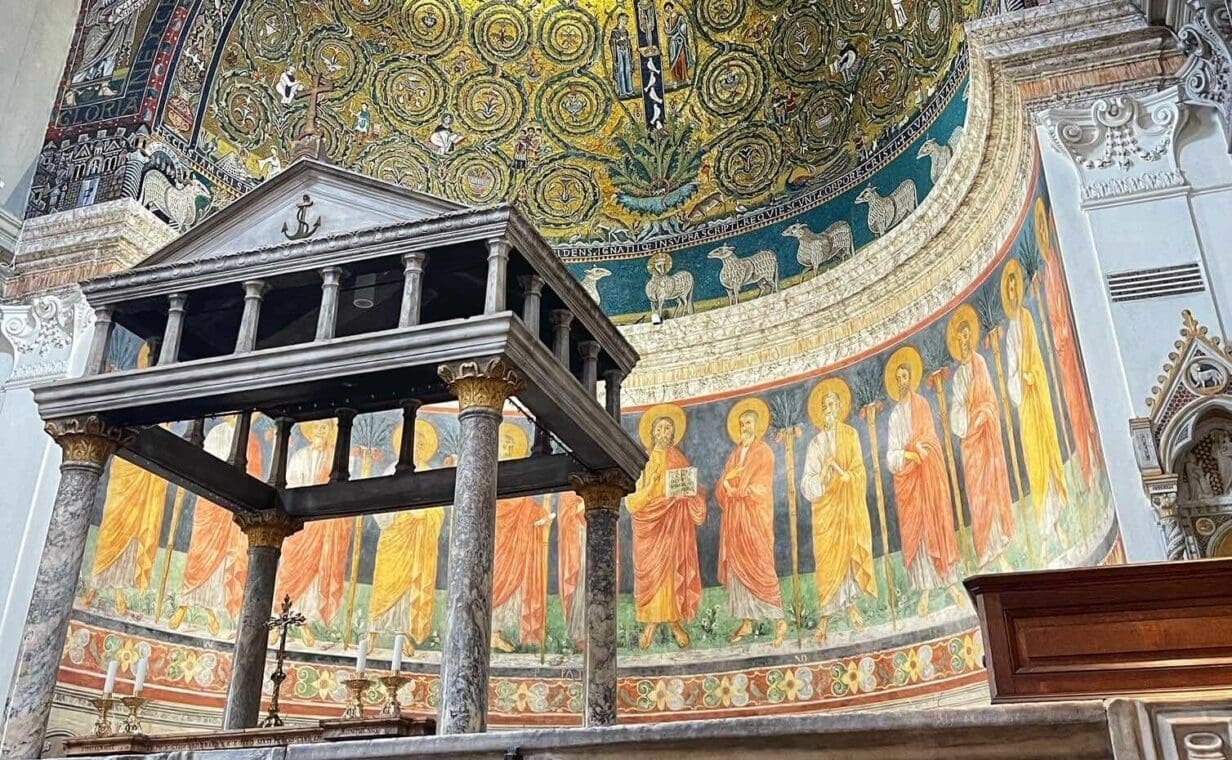

It’s an exhausting climb up a steep 124-step marble staircase to reach the entrance to the Romanesque church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli high atop Rome’s Capitoline hill, but what splendours await those who make it to the top!

Located on the site of the ancient temple of Junio Moneta and enjoying commanding views over the city, Santa Maria in Aracoeli is the official church of the city council of Rome. Spectacular medieval architecture, a stunning Cosmatesque floor and an array of precious artworks makes the basilica one of Rome’s most spectacular churches, and a must stop when visiting the Capitoline Hill.

Amongst the many highlights within, the glittering first amongst equals is the Bufalini chapel just to the right of the basilica’s entrance. A fabulous Cosmatesque pavement lines the floor, whilst the walls and the ceiling are covered with extraordinarily vibrant frescoes by 15th-century master painter Pinturicchio depicting the life and times of the firebrand Franciscan preacher Saint Bernardino of Siena. The frescoes offer an incredible window into the magical world of early modern Italy, with its miracles and its saints, its courtly rituals and its violent dramas, and the Bufalini chapel is one of our favourite showcases of Renaissance art in Rome.

Discover it with us!

Rome Tours

Explore a Hidden Side of the Eternal City

The Artist

Bernardino di Betto was born in Perugia in 1454, and quickly established himself as one of the foremost painters of the Umbrian school alongside the slightly older Pietro Perugino. Known to all as Pinturicchio, or the Little Painter, on account of his diminutive stature, Bernardino’s career really kicked off when he was called to Rome as part of the squadron of painters hired by Pope Sixtus IV to carry out the first programme of decorations in the newly completed Sistine Chapel. There he worked alongside not only his colleague Perugino, but also up-and-coming Florentine painters like Botticelli, Ghirlandaio and Signorelli.

Taking advantage of the lack of homegrown artistic talent in Rome during this period, Pinturicchio elected to remain in the Eternal City to open his own workshop, and soon work came flooding in from the city’s richest and most influential patrons. Major commissions in Santa Maria del Popolo from the Della Rovere and Cybo families were soon followed by receiving the prestigious honour of decorating the private apartments of the notorious Borgia Pope Alexander VI at the Vatican, which today remain one of the finest testaments to Renaissance painting in Rome.

Outside of Rome, Pinturicchio left a string of masterpieces across the fortified towns and city states of Umbria, including a series of panel paintings in his native Perugia depicting the miracles performed by Bernardino of Siena in an oratory dedicated to the saint. When the influential papal lawyer Niccolò Bufalini called on his fellow Umbrian Pinturicchio to provide paintings for his family’s chapel in the Roman church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli in the mid 1480s, it was once again the life of Saint Bernardino that would be in the artist’s sights. But who was the holy man in question?

The Saint

Without doubt one of the most revered ‘new’ saints of the 15th century, Pinturicchio’s namesake Saint Bernardino da Siena was a firebrand Franciscan preacher whose intolerant sermons shocked and delighted his dazzled audiences in Siena and made him one of the most renowned figures of his generation. Railing against what he saw as the lapsed state of religious observance in Quattrocento Italy, Bernardino excoriated the masses for crimes as varied as gambling and witchcraft, money-lending and sexual profligacy.

A bile-filled hatred of homosexuality (a practice that had heretofore been largely tolerated in contemporary Tuscany) permeated many of his public speaking engagements, and were instrumental in hardening attitudes against the ‘crime’ of sodomy in Siena during his lifetime. Equally virulent were his views on Gypsies and Jews, whose communities he argued should be segregated from their Christian neighbours.

Despite (or perhaps because of) his over-the-top ranting and reputation for extreme intolerance, Bernardino soon became a cult figure, and a series of paintings in Siena’s Museo dell’Opera del Duomo show the entire city assembling in the Piazza del Campo to listen to the saint-to-be’s sermons. Bernardino was canonised in 1450, just 6 years after his death, and countless artworks were commissioned in the coming decades to burnish the new saint’s legacy. Amongst these, the Bufalini chapel in Santa Maria in Aracoeli is the undisputed highlight.

The Patron

A native of the Umbrian town of Citta di Castello, Niccolò Bufalini quickly rose through the ranks of the Catholic church hierarchy and moved to Rome to take up a senior position in the Curia in the 1460s. His star rose even higher during the papacy of Pope Sixtus IV when he was appointed a consistorial lawyer at the Vatican, and it was whilst he held this office that he commissioned Pinturicchio to fresco the family chapel at Santa Maria in Aracoeli with grand paintings celebrating the life of San Bernardino.

Niccolò was personally devoted to the figure of Bernardino thanks to his intervention in an unseemly spat his family were embroiled in. Even before Niccolò’s rise to prominence in Rome the Bufalini had been amongst the most powerful families in Umbria, and their legendary feud with the rival Baglioni clan of neighbouring Perugia had raged throughout the 15th century (Pinturicchio, incidentally, was responsible for the decorations of the Baglione Chapel in the town of Spello, one of the great highlights of Umbrian Renaissance painting). Bernardino had been an instrumental figure in brokering an uneasy peace between the warring families, and an easy-to-miss detail in one of the frescoes references Bernardino’s role in putting a halt to the hostilities.

The saint is pictured displaying a crucifix to an armed warrior bearing the crest of the Baglione family on his shield, a bloody corpse crumpled at his feet. Amongst other nearby figures brandishing swords is one whose shield is emblazoned with a bull’s head, the distinctive emblem of the Bufalini. The message is clear – the carnage being wreaked in this internecine conflict could only be halted by the intervention of a higher power.

Niccolò himself is buried beneath the stones of the chapel, protected for all eternity by the withering gaze of his beloved Bernardino.

The Vault

The cross-vaulted ceiling is divided into triangular pendentive fields which feature the four evangelists seated on clouds and framed by golden mandalas. Combining a monumental solidity that showcases Pinturicchio’s grasp of perspective and three-dimensional modelling with boldly rendered poses – the evangelists peel open books and brandish pens with disarmingly lifelike dynamism – the artist’s full range of skills is in evidence here.

Altar Wall: The Glory of San Bernardino

The central scene of the fresco cycle depicts Saint Bernardino ascending towards heaven in glory as two cloud-borne angels carrying lilies in their hands hold a crown above the preacher’s head. Wizened old Bernardino stands on a ragged crag and holds an open book in his left hand, pointing heavenward with his right: the text on the page reads PATER MANIFESTAVI NOMEN TVVM (H)OMINIBVS – a reference to Bernardino’s reverence of the Christogram IHS, which earned him a charge for heresy from which he was eventually absolved by Pope Martin V.

Flanking Bernardino are Saint Anthony of Padua, another prominent Francisan preacher who clutches his own flaming heart, and St. Louis of Toulouse, a 13th century Neapolitan prince who gave up his feudal birthright to follow the example of Saint Francis, eventually becoming archbishop of Toulouse.

In the skies above, meanwhile, Christ watches over Bernardino’s coronation from a heavenly mandala as elegant angels strum on lyres and pluck lutes, blow through trumpets and raise their voices in divine song.

The surrounding landscape is one of the most delightfully picturesque natural vistas ever depicted in the Renaissance, a world of rocky cliffs and soaring trees giving way to a placid sea framed by distant mountains. Look carefully at the path that leads down from the mountainside behind St. Louis and you’ll see the unfolding conflict between the Baglioni and the Bufalini factions, stilled at a glance by the haloed Bernardino.

Left Wall

The Death of Saint Bernardino

The most celebrated fresco in the chapel ostensibly depicts the funeral of Bernardino, but Pinturicchio’s tour-de-force on the left hand wall is much more than a simple narrative of the saint’s obsequies. Unfolding in the open piazza of an ideal Renaissance city that appears to have been inspired by the experiments in painted architecture of Pinturicchio’s old colleague Perugino, the lifeless saint lies on a catafalque as he is surrounded by a throng of onlookers.

Pinturicchio displays the full expressive capacity of his art in the extraordinary variety and individualism of the characters that mill in and around the bier on which Bernaridino rests. The saint’s fellow Franciscans bow their hooded and tonsured heads in grief; overcome with emotion, one monk wipes a tear from his eye. To either side of the deathbed noble figures in opulent contemporary dress strut and stare frankly out of the pictorial space, whilst women chat amongst themselves as one breastfeeds a baby oblivious to the events unfolding before him.

Many of these figures are almost certainly genuine portraits of members of the commissioning Bufalini family, and the sombre, sumptuously-dressed man at the far left of the painting holding a glove in his hand has been convincingly identified as the patron Niccolò Bufalini.

Of course, one of the main purposes of a fresco cycle like this was to burnish the reputation of the saint himself, and so dotted around this scene are miracles associated with Bernardino. Directly behind the catafalque is a group of ragged beggars and pilgrims; one, sporting the distinctive scallop shell of St. James – a symbol of pilgrimage – on his cap, points to his eyes to indicate that his blindness has been miraculously healed thanks to his close proximity to the saint.

In the scene’s foreground a swaddled infant lies happily gurgling in his manger, recalling Bernardino’s legendary resurrection of a still-born child. Amidst the beautiful loggias in the background we can just about make out the warring factions of the Bufalini and Baglioni having it out once again, the violence about to be stilled by Bernardino’s intercession. In the middle ground to the far right, finally, a demon-possessed woman is returned to her senses.

Take a close look at the group of figures to the right of Bernardino, and right at the edge of the frame you’ll spy a well-built man sporting a natty red cap – this is Pinturicchio himself, making a surprise guest appearance!

Right Wall

Bernardino receives the habit

The chapel’s right wall is divided by fictive illusionistic architecture into three separate ‘windows’ which open onto landscapes that seem to dissolve the architecture of the church itself. To the left we see the kneeling young Bernardino, recognisable by the shining halo circumscribing his tonsured head and nude except for a flimsy loincloth, receiving the robes of the Francisan order from a senior monk.

A begging bowl lies on the ground beside him, reminding us of the vow of poverty that was fundamental to the Franciscan way of life. Other hooded Franciscan monks look on, framed by elaborate pillars carved with grotesque antique decorations – a reference to the patterns that Pinturicchio had seen in the ruins of Nero’s Golden House, which was being excavated at this time.

The central ‘window’ frames five figures that seem almost certainly drawn from life, such is the distinctiveness of their faces and physiognomies. The elderly Franciscan who raises an admonitory finger as he stares into the chapel is likely to be a portrait of the convent’s prior. The scene to the far right also references the Franciscan journey of Bernardino, as here Francis himself is pictured receiving the stigmata in a rocky wilderness.

Dive Deeper into Rome