“Without having seen the Sistine Chapel one can form no appreciable idea of what one man is capable of achieving.” – Goethe

The Sistine Chapel is one of the greatest artistic achievements of all time, a must-see for anyone visiting Rome. In the Sistine Chapel you will discover the revolutionary ideas of the Renaissance, learn about the historical context of the art, and what influenced and inspired the great artists of the time. Visiting the chapel on a private Early Morning Sistine Chapel Tour makes the experience even more unique.

When you enter the chapel it can be difficult to know where to look, as it seems as though every inch of the ceiling and walls is swarming with the figures of saints, demons, and everyone in-between. Frescoes include Botticelli’s Stories of Moses, Perugino’s Stories of Jesus, and Michelangelo’s legendary ceiling.

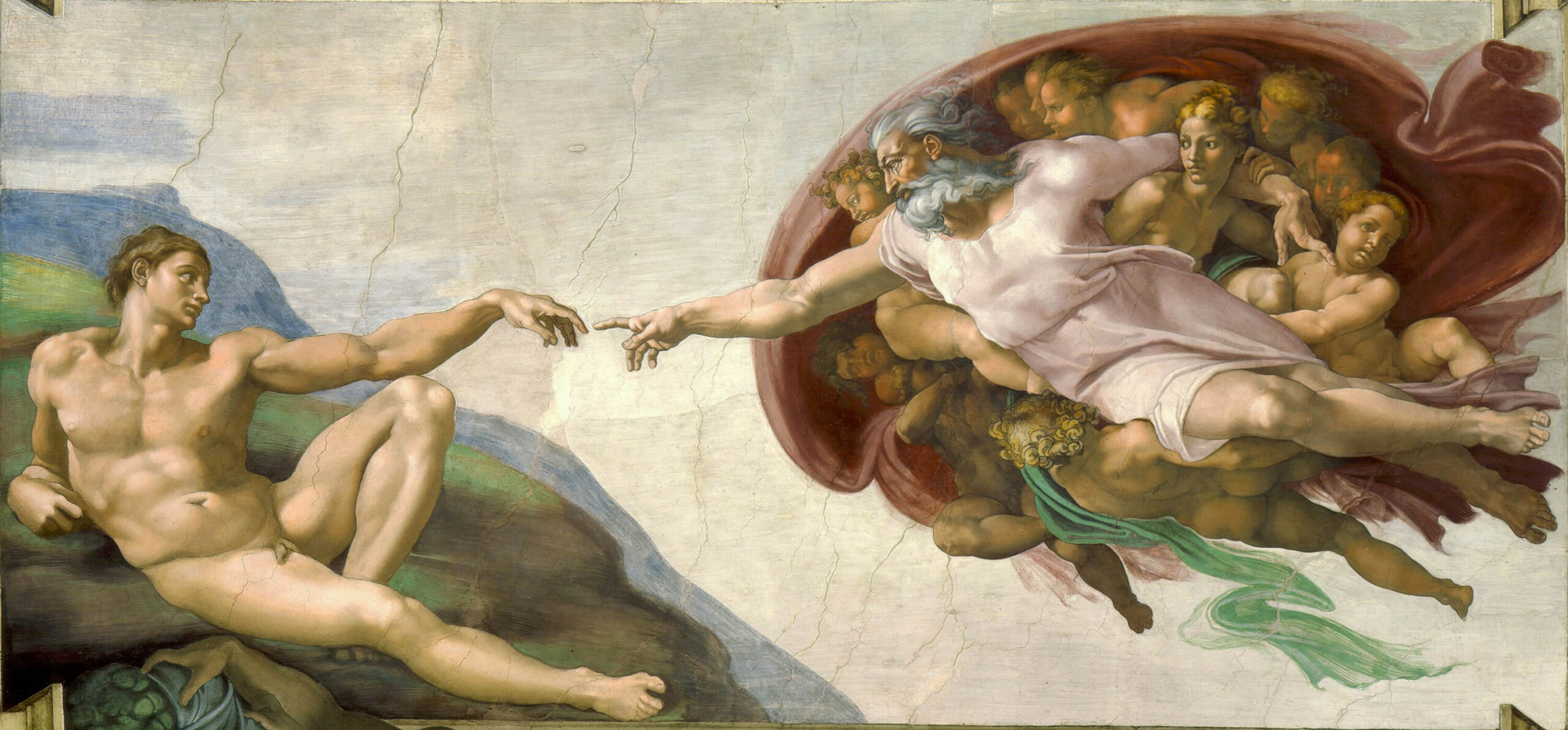

The best way to make sense of the Sistine Chapel without succumbing to Stendhal Syndrome is to explore the Vatican with a knowledgeable guide, who will explain the different sections of the masterpiece, from the Creation of Adam to the Great Flood. There’s more to the paintings than meets the eye, and though it may be hard to believe now, one section of the Sistine Chapel is perhaps the most controversial of all of Michelangelo’s works.

Vatican Tours

Find Your Perfect Vatican Itinerary

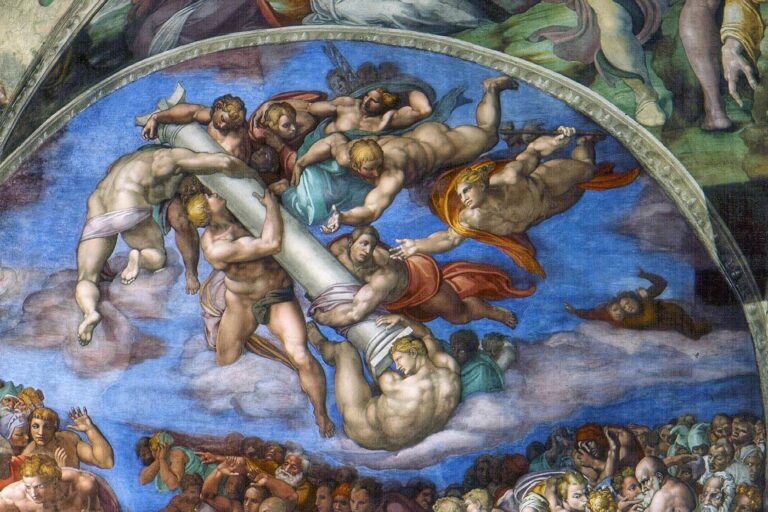

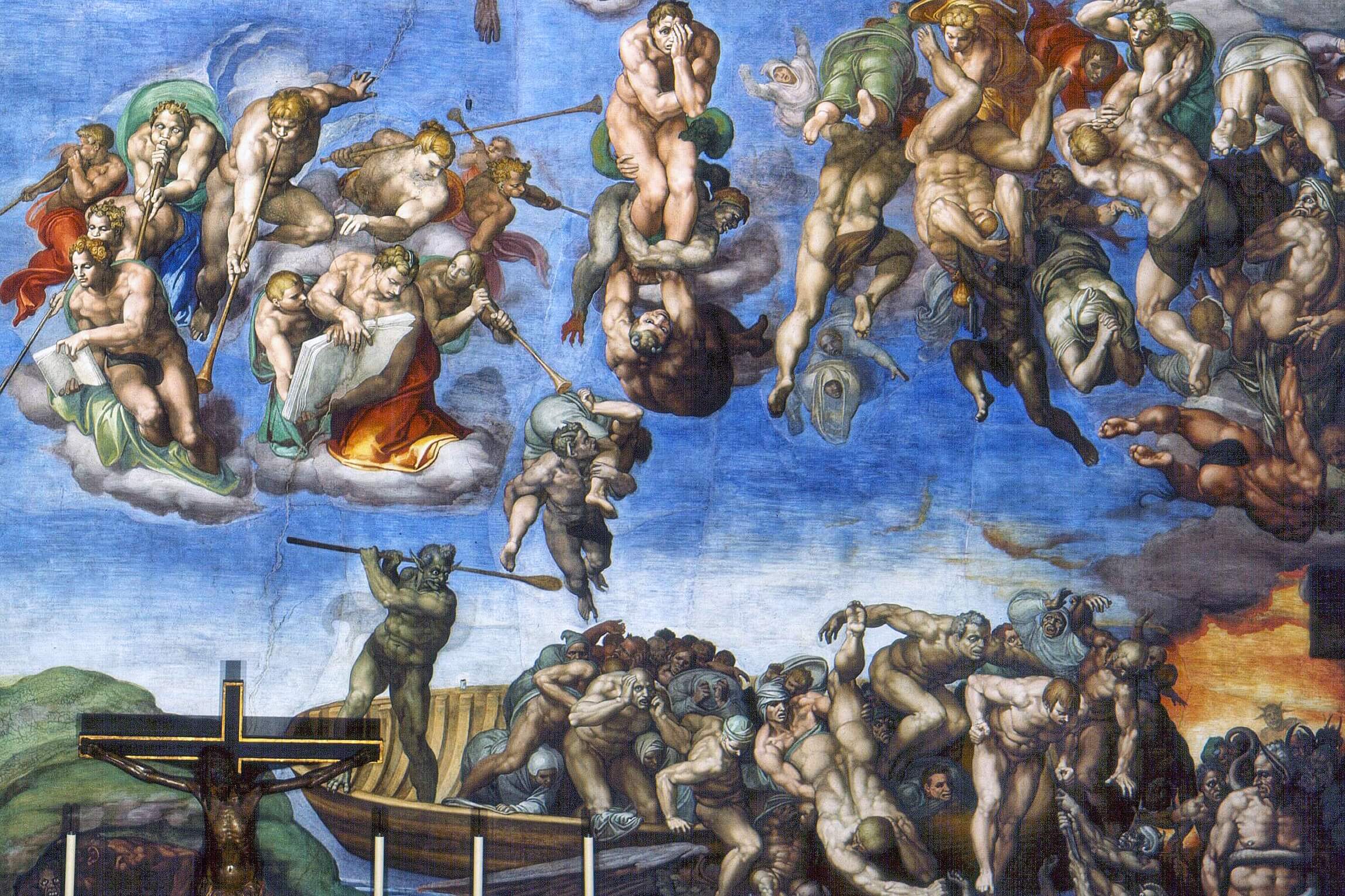

The Last Judgement, painted from 1535 to 1541, covers the entire altar wall of the Sistine Chapel. It depicts the second coming of Christ on Judgement Day, surrounded by apostles, disciples, saints, martyrs, angels, demons, the saved ascending to paradise and the damned being dragged to hell. It’s an extraordinarily complex and detailed scene, especially given the enormous size of the fresco. Painted twenty-five years after the completion of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, The Last Judgement is the work of the mature Michelangelo, at the peak of his artistic powers.

The work had been commissioned by the Pope, but many Catholics felt that The Last Judgement was inappropriate for a place as sacred as the Pope’s private chapel. The Papal Master of Ceremonies, Biagio da Cesena, deemed the fresco outrageous, and more suitable for public baths or taverns than a chapel. “….it was mostly disgraceful that in so sacred a place there should have been depicted all those nude figures, exposing themselves so shamefully”. Michelangelo responded by making Minos, judge of the underworld, resemble Cesena. It’s an extremely unflattering portrait; Minos/Cesena has the ears of a donkey and a snake biting his genitals. When Cesena complained to the Pope, the Pope reportedly pointed out that his authority did not extend to hell. The painting remained unchanged.

But Cesena was far from the only detractor. The satirist Pietro Aretino, angered when Michelangelo ignored his advice, accused the artist of being “godless” and homosexual – a little hypocritical, given Aretino’s boasts about his own same-sex conquests. The obvious response was to include Aretino in the painting, which Michelangelo promptly did. St Bartholomew, portrayed as a stern old man holding his own flayed skin, bears a striking resemblance to Aretino. Interestingly, the face on the flayed skin of the saint has been interpreted as Michelangelo’s anguished, distorted self-portrait.

The controversy over nudity in the Sistine Chapel continued after Michelangelo’s death. The artist Daniele da Volterra was hired to cover up some of the genitals in The Last Judgement by adding fig leaves and loincloths, which earned him the nickname “Il Braghettone” (“The breeches maker”).

When the Sistine Chapel underwent a controversial restoration in the 1980s, many expected Volterra’s “breeches” to be removed. But while some additions by later artists were removed, the restorers decided that Volterra’s work had become an important part of the history of The Last Judgement. The director of the Vatican Museums, Fabrizio Mancinelli, believed that Volterra may have helped to preserve Michelangelo’s masterpiece, as it was spared by the Council of Trent during their destruction of other artwork in Rome in the sixteenth century. Mancinelli’s conclusion: “We must be respectful of these breeches.”

The restoration work removed layers of grime, revealing bright colours and interesting details that had been hidden for centuries, such as the snake biting Minos. Despite criticisms that the restorers were damaging the frescoes and that the new colours that emerged were not representative of Michelangelo, most now agree that the restoration was necessary. Without the work of the restorers, we would not be able to see the vivid blue of the sky in The Last Judgement or Michelangelo’s subtle revenge on his critics.

To admire the Sistine Chapel and other Renaissance treasures in the Vatican Museums, learning about Michelangelo and his contemporaries in their historical context, check out our range of expert-led Vatican tours below!

Explore the Sistine Chapel