To single out details from the great dream of Roman Churches, would be the wildest occupation in the world. But St. Stefano Rotondo, a damp, mildewed vault of an old church in the outskirts of Rome, will always struggle uppermost in my mind, by reason of the hideous paintings with which its walls are covered. Such a panorama of horror and butchery no man could imagine in his sleep, though he were to eat a whole pig raw, for supper.

– Charles Dickens, Pictures from Italy

Rome, as everybody knows, is a city of churches. From imposing St. Peter’s to Santa Maria Maggiore, the Eternal City boasts some of the oldest and most beautiful churches in all the world. But for the intrepid traveller ready to look beyond the guidebook highlights, there are some truly incredible hidden gems just waiting to be discovered too.

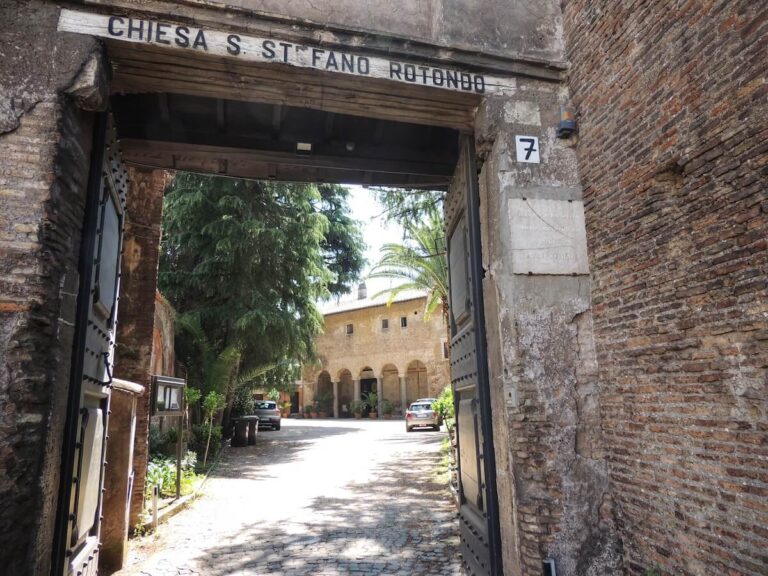

For sheer dramatic effect, none can match the ancient circular church of Santo Stefano Rotondo on the leafy slopes of the Celian hill. One of our favourite off-the-beaten-path sites in all the city, this massive 5th-century edifice is a treasure-trove of spectacular early-Christian architecture. And that’s not all – Santo Stefano is also home to some of the most bizarre, off-the-wall, gruesomely violent frescoes ever painted, the fruits of a redecoration campaign carried out when the church became the property of a Jesuit noviciate college in the late 16th century.

Best Rome Tours

Explore the Best of Rome

The Church

From Temple of Light to House of Horrors

These days the out-of-the-way church and its outré decorations rarely find themselves on the tourist radar, but in centuries past Santo Stefano constituted a sensational highlight for travellers on the Grand Tour. When Charles Dickens stopped by on his Italian voyage in the 1840s, the images seemed to him the product of some horrifying trichinosis-induced nightmare – his lurid account of them is perhaps as readable as anything he ever penned in his glittering novelistic career. The usually un-shockable Marquis de Sade meanwhile found the perversely graphic violence on show to be too extreme even for his debauched tastes.

So forget everything you thought you knew about Renaissance ideals of harmony and good taste; park your visions of Leonardo, and leave Raphael on the threshold – this is religious art as you’ve never seen it before.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Before we get to the gory stuff, we need to take a trip back in time – over a millennium in fact, to the late fifth century, when the Liber Pontificalis tells us that the church was consecrated by Pope Simplicius. At the time Santo Stefano would have been one of Rome’s biggest churches, rivalled only by the Apostolic basilicas of San Pietro and San Paolo fuori le Mura.

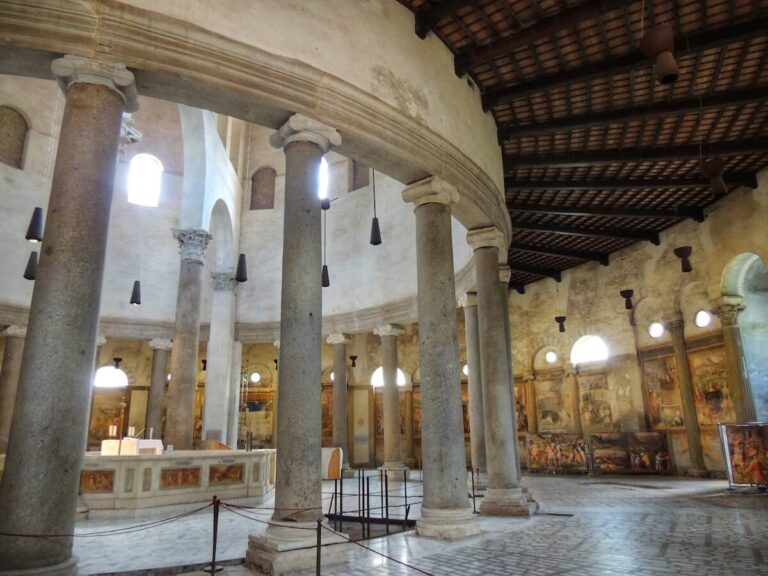

Given it’s huge size and unusual centralised plan, for centuries it was believed that Santo Stefano was an adapted pagan edifice, but it now seems certain that Santo Stefano was a Christian building from the beginning, built over the top of an ancient complex that included a barracks and mithraeum. And the architecture is truly spectacular.

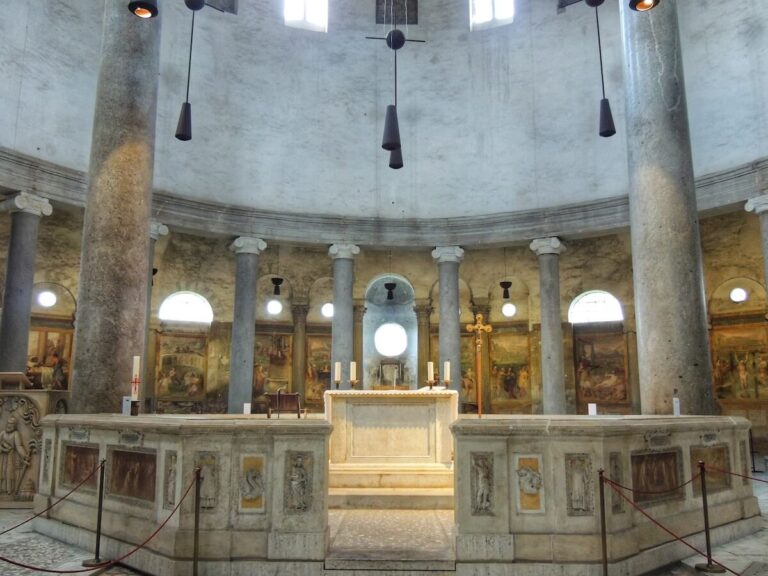

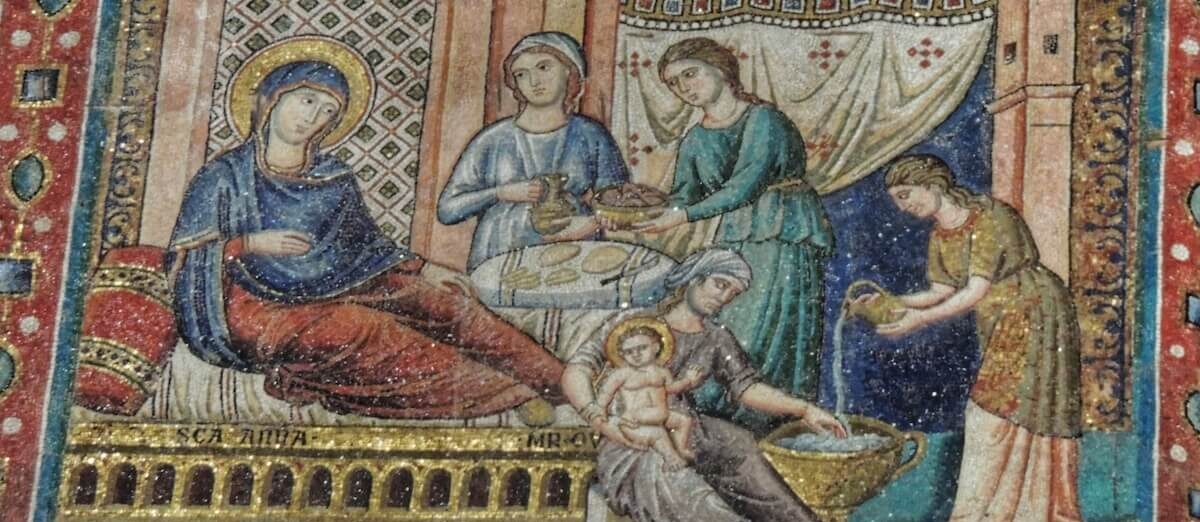

The largest circular church in Rome, entering Santo Stefano is like entering into a temple of light. At the centre of the basilica is a great ring of marble columns surrounding an octagonal altar right at the centre of the church. Everything is beautifully lit by the soft light flooding in from windows in the drum high above – little wonder that this most spectacular of churches is one of Rome’s most popular wedding destinations. But not everything is as it seems.

Peer through the dense forest of columns that ring the ambulatory, let your gaze settle on the massive paintings that cover every inch of the church’s gloomier outer walls and prepare yourself for a shock. For this temple of light is about to transform into a house of horrors.

The Frescoes

Blood, Guts and Martyrdom

Grey-bearded men being boiled, fried, grilled, crimped, singed, eaten by wild beasts, worried by dogs, buried alive, torn asunder by horses, chopped up small with hatchets: women having their breasts torn with iron pinchers, their tongues cut out, their ears screwed off, their jaws broken, their bodies stretched upon the rack, or skinned upon the stake, or crackled up and melted in the fire: these are among the mildest subjects. So insisted on, and laboured at, besides, that every sufferer gives you the same occasion for wonder as poor old Duncan awoke, in Lady Macbeth, when she marvelled at his having so much blood in him.

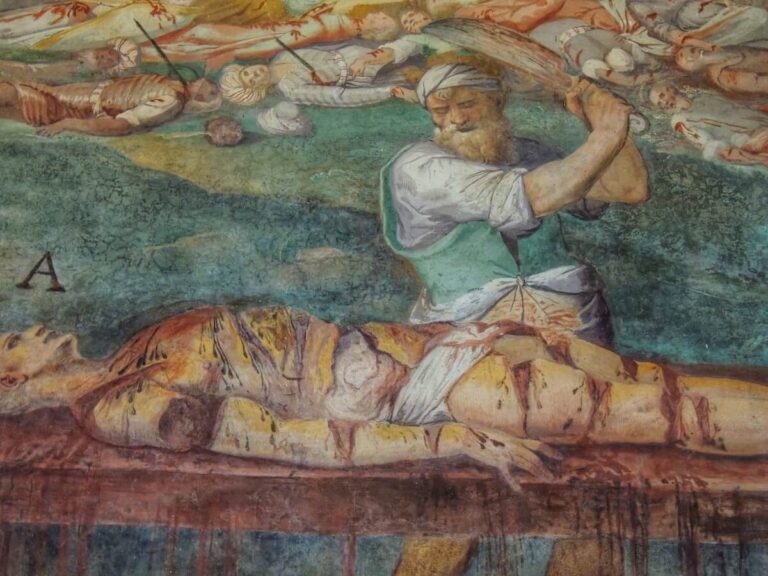

That was Charles Dickens’ evocative hot-take back in the 19th century, likening the experience of viewing these frescoes as akin to a trichinosis-induced fever dream. And he wasn’t wrong. Torture, maiming, desecration, death. Over the course of thirty frescoes that ring the entire church, an endless sequence of body horror assails our eyes.

This massive commission constitutes arguably the most sustained interrogation of martyrdom ever produced. Beginning with the crucifixion of Christ and the Massacre of the Innocents, Santo Stefano’s fresco cycle takes us through a particularly disturbing history of Christianity where bodily destruction is the narrative key that sets everything in motion.

Each fresco depicts violent scenes culled from the annals of the early church, a vertiginous panorama of blood-letting that unfolds serially around the vast circular space of the basilica. Helpful captions beneath each image inform us who is who in Italian and Latin text, which persecution we are gazing on and whose body we are watching being torn apart before our eyes.

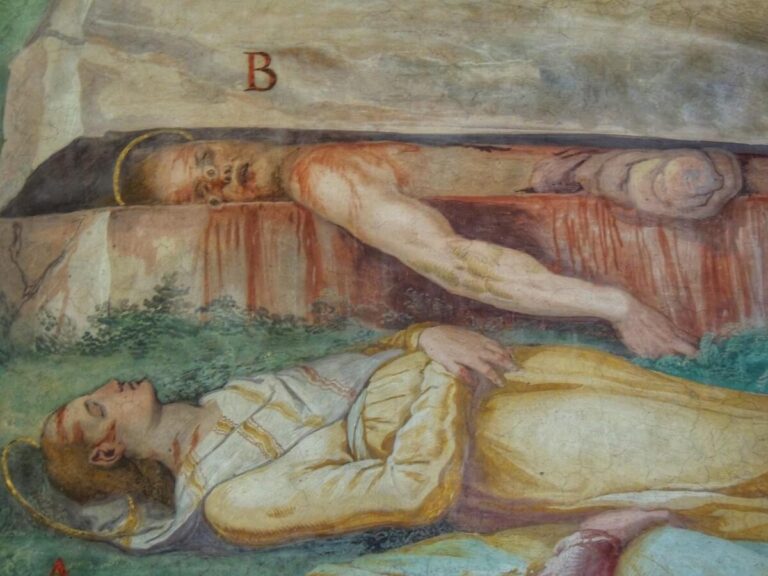

With invention that even the greatest slasher directors would struggle to match, at Santo Stefano each pictorial field reveals some new and unusual atrocity. As the horrors continue, they somehow intensify. In this, the church’s most vivid fresco and perhaps one of the most striking renderings of violence ever painted, a naked man is stretched out on a butchers block, whilst a machete-wielding psychopath hacks and hacks again at his lifeless body. Bones protrude from his flesh, and rivers of blood gush down the wall, sanctifying the space with the sacred power of sacrificial blood.

And the gore doesn’t let up. In another lurid scene we are confronted with the death of the unfortunate saint Artemius, his body crushed between two enormous slabs of stone. Artemius, the story goes, upset the pagan emperor Julian the Apostate, who responded with unsurprising brutality.

The artist, Niccolò Circignani, lingers on the minutest details of the saint’s bodily desecration with apparent delight, painting eyes popping out of their sockets and bowels seeping out of a torso split apart by the unbearable stony weight. A halo ringing the saint’s head is the only object not crushed by the slabs, indicating Artemius’ reward is in heaven.

We could go on, pointing out forests where the tree boughs are festooned with amputated limbs, or cooking pots in which holy flesh meets boiling oil; we could describe piles of corpses being tossed into fiery furnaces and icy lakes, or young women cast into dens of poisonous vipers.

Even the strongest constitution is sure to be challenged by the depiction of Saint Agatha, her breasts torn off with pincers by an executioner whose grim visage marks him as entirely indifferent to his horrifying task. Descriptions, however, can take us only so far: to get the full effect, this is one site-specific collection of art you really need to see in person.

But just what exactly is going on here?

The Order

Jesuits and the Counter-Reformation

When the venerable but crumpling church passed into the hands of the Jesuit-run German-Hungarian college in the 1580s, it was in a dire need of repair. As part of his attempt to restore it to its former glory, the new rector Michele Lauretano wasted little time in hiring the successful painter Niccolò Circignani to adorn the walls of Santo Stefano with scenes depicting the suffering and death of a range of early Christian martyrs, the first example of a new taste for violent martyrdom imagery that would become a craze in Rome over the coming two decades – Circignani himself would author at least two more such cycles at the Jesuit English College and the church of Saint Apollinaire.

Look out for his self-portrait at Santo Stefano in the guise of the bestubbled figure looking out from the group observing with astonishment the sight of Saint Dionysius carrying his own severed head in a procession through a cheery bucolic landscape in one of the frescoes.

The reason for this new-found enthusiasm in recalling the gory persecutions of the saints can be found in the specific political climate of 16th century Europe. The Santo Stefano frescoes were commissioned during the violent ferment of the religious wars in the 16th century, when Catholic and Protestant factions sought to establish themselves as legitimate heirs to the true faith of the early Christian church.

On the front line of attempts to return the newly Protestant lands of northern Europe to the Catholic fold, vast numbers of Jesuit missionaries made their perilous way northwards from their home bases in Italy armed with nothing more than doctrine in their dangerous efforts of proselytisation and conversion in hostile lands.

Persecution, torture and death were ever-present possibilities for the young Jesuits, and the frescoes of Santo Stefano seem to emphasise to the novices that they would be following in a noble tradition of steadfast Christians willing to risk their lives in the defence of their faith. The frescoes must have left the young men under no illusions as to the dangerous nature of their mission.

Go and preach the faith, they seem to say, and a grisly end might well be in store for you. But you’ll be working for God, and there can be no greater reward than to join the ranks of these heroic role models that look down on you with bloody eyes from the walls of the basilica.

For Catholics the age of martyrdom was the golden age of the faith, and Rome was its blood-spattered ground zero. Everywhere in the Eternal City relics of that distant age of zealotry were being brought to light. The excavation of the catacombs seemed to open a new window into the world of early Christianity itself, whilst relics and bodies were being transported all across the city in magnificent processions. In Rome in the 1580s, there was nothing less than a mania for the bodies of the saints, and an obsession for stories of their heroic deeds. The frescoes at Santo Stefano filled that need, vivid visual reminders of the sacrifices on which the faith was founded.

Circignani’s frescoes haven’t fared well in the court of public and art historical opinion over the centuries, described variously as horrifying, nauseating and propagandistic anti-art by critics left cold by the excessive gore. But for their first viewers, the power of these strange and disturbing images was undeniable. On a visit to the church shortly after their unveiling in the 1580s, Pope Sixtus V couldn’t stop himself from weeping before the glistening painted atrocities, and innumerable contemporary accounts describe the tear-stained eyes of all who came to admire them.

Gazing on the images today, which seem so over-the-top to our 21st century sensibilities, it is difficult to imagine the depth of feeling that so moved contemporary observers. But the Santo Stefano frescoes remain a fascinating and invaluable document of a little-known period in Rome’s millennial story, a reminder that artworks always have their own specific contexts and functions, and are far more than just pretty pictures passed down through the centuries.

Book Your Rome Experience