For thousands of years, humankind has been captivated by the mysterious power of the image. But what is this strange power? When the French writer George Stendhal came to Florence in 1817, he experienced first-hand its disarming effects. Physically overcome by the weight of cultural riches spread out before him, his heart began to palpitate wildly, and it was all he could do to stop himself from fainting. And so was born the Stendhal Syndrome, an unusual condition whose sufferers experience an overpowering sensation of weakness in the presence of high concentrations of very great art. This is the revenge of the museum, and it could happen to you.

Vasari, the Uffizi and the Birth of Art History

This is the Uffizi. Hidden behind this majestic façade that seems to float light as air over the city of Florence lies one of the world's greatest collections of art. Though originally intended to be an administrative building, it wasn't long before the Uffizi began to be associated with the art world and by 1581 it could lay claim to being the modern world's first public art gallery.

Some of the first viewers of the Medici collection would foreshadow the overwhelmed Stendhal's reaction to the city over 200 years later. According to one, “the eye sweeps over so many magnificent things, so different, so rare, so sublime, that it is overcome by such delight that the soul almost faints.” It’s difficult not to share his sense of wonder when visiting the Uffizi - for here the entire history of the Renaissance is set before us in spectacular microcosm.

This magnificent building was designed by Giorgio Vasari, widely regarded as the modern world's first art-historian. It is to Vasari that we owe many of our conceptions of what art is and how we write its history. He saw art as the quest to imitate and finally perfect nature itself, a process that would culminate in the masterpieces of the High Renaissance.

For Vasari, the chronology of the Renaissance was a chronology of progress, and the collection of the Uffizi is ordered on those same lines today. Though we too will follow this path through time as we explore the Uffizi’s collection, there are more interesting ways of interacting with these great works. For each and every one of the paintings here are fragments of time, snapshots of history immortalised in art. A visit to the Uffizi is the chance to open windows onto distant worlds.

Medieval Beginnings: The World of Faith

We begin where Vasari began his own history of art, with the enormous altarpieces of Giotto and Cimabue. We find ourselves immersed in the mysterious world of 14th century Christianity. In their wonderfully expressive yet unearthly forms, these paintings in gold and precious pigments seem to be trying to reach towards heaven itself. Naturalism has no place here. For what sense did it make to attempt to represent the divinity of the Virgin Mary or of a choir of angels as if they were subject to earth's physical laws, as if they were mere mortals?

These paintings aren't realistic – their figures aren't in proportion and they don't occupy a believable space. But don't mistake this for crudity for lack of ability. They are merely expressing another reality, the reality of a faith that was held with a fervour that many of us find it difficult to understand today. To understand their forms is to divest ourselves of our own modernity, to enter fully and uncynically into the contours of a distant past.

The Early Renaissance: A New World Awakens

With a few short steps we have jumped forward in time, forward 150 years to the middle of the 15th century. The world, and the world of art, has changed almost beyond recognition. This is a world of warring city states, of battles like the one that raged between Florence and Siena depicted in Paolo Uccello's Battle of San Romano. So precious was the memory of that glorious victory to the Florentine Republic that Lorenzo de Medici had it hanging above his head whilst he slept.

Christian piety was still of course of great importance to the artists and patrons of the 15th century, but there were new heroes to be honoured, new subjects fit to be memorialised by the painter's brush. When the ruthless warrior-prince Federico da Montefeltro commissioned Piero della Francesca to paint his portrait, it was in the image of a triumphant Roman emperor and not a humble Christian supplicant.

The rich learning of the classical world also became fertile material for artists patronised by the great humanists of the Renaissance, and foremost amongst them must be this man, Sandro Botticelli. His enchanting impressions of pagan mythology perhaps epitomise contemporary fascination with the capacity of beauty to elevate the spirit more profoundly than any other. We are standing before the artist's iconic Birth of Venus. The goddess of love, born from the foam of the ocean's eternally crashing waves, is being carried triumphantly to shore towards us, blown along by the breath of the gods. In its pagan lyricism it is a painting that would be unthinkable for Giotto and his contemporaries - but now Venus is triumphant once more, feted by the greatest thinkers of Renaissance humanism.

The High Renaissance: A Season of Giants

As the years tick by towards the 16th century, we have finally reached the High Renaissance. This age of giants was the pinnacle of Vasari's artistic pyramid, a period in which nature herself had been perfected. The great artists of the age are forging ahead in very different directions, serious and profound, and the lightness of Boticelli's art has disappeared back into the ocean waves.

Here is Leonardo da Vinci, the first of Vasari's High Renaissance masters. Brilliant and eccentric, Leonardo's unique approach to art is perfectly encapsulated in this, his unfinished Adoration of the Magi. The landscape is complex and ambiguous, and bears little relationship to traditional representations of this popular biblical scene. As we gaze at this whirlwind of figures and events, from pagan temples to pitched battles, space itself seems to take on an expressive character all its own.

The old subjects are finding new modes of expression. Take Titian's Venus of Urbino, which in its daring realism is more provocative than anything Botticelli ever painted. In a material world recognisable as our own, Venus reclines provocatively before us as a woman, not a goddess. In its unflinching sexuality it is a world away from Botticelli's learned mythological fantasy and the academic climate of 15th century Florence. Indeed, this is the art of Venice, sensual, worldly and dynamic.

The art of Raphael, with its series of marvellously graceful Madonnas, might seem altogether less radical. But there was more to the man known as the 'prince of painters' than just pretty pictures. Raphael possessed one of the most incisive eyes in the history of art, and with this masterly portrait of Pope Leo X he immerses us into the intrigues of papal politics. Not only is it a painting of immaculate skill, it is also a penetrating analysis into the psychology of power that would revolutionise portraiture in generations to come.

We finally come to Michelangelo, the man who according to Vasari dwarfed all others with the terrible power of his art. This is his Doni Tondo, the only completed oil painting by him that survives today. What are we to make of the strange heaviness of the figures, their contorted poses and the suffocating lack of pictorial space? The lyrical delicacy of the 15th century has been well and truly obliterated, and art has reinvented itself once again.

The Baroque and Beyond: A Shattered Ideal

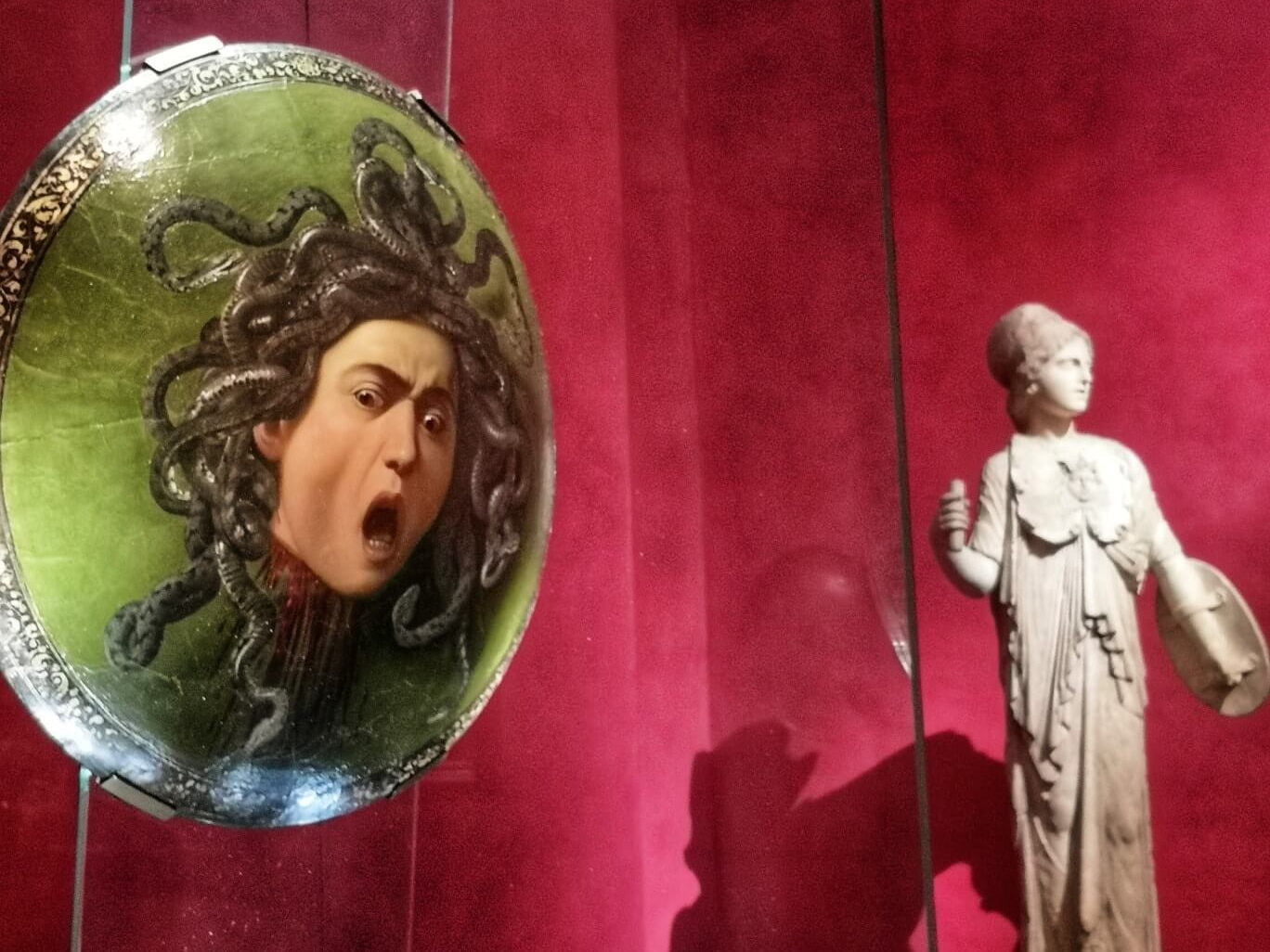

We must make one last leap in time. It is with a shock that we find the Renaissance over, its memory scattered in the ashes of a Rome sacked by Charles V's mutinous troops. We are at the beginning of the 17th century, and in the terrifying world of Caravaggio. Vasari's narrative lies in tatters – for where could the ferocity of Caravaggio's expression fit into his theory of nature perfected?

No wonder contemporaries thought of him as an avenging angel come to destroy painting itself. And yet, as we lock gazes with his terrible Medusa, staring back at us with inhuman fury, we perhaps see the strange power of art given its fullest expression. You might not be turned to stone like Medusa's ancient victims and you might not succumb to Stendhal's fainting fit, but you most certainly will be affected. Come see for yourself.

MORE GREAT CONTENT FROM THE BLOG:

- Everything You Need to Know to Visit Florence in 2025

- The Best Things to Do in Florence in 2025

- Where to Stay in Florence

- The Best Tours of Florence

- The Best Museums in Florence

- What to See in the Uffizi Gallery

- The Best Street Food in Florence

- Where to See Michelangelo in Florence

Through Eternity Tours offer a range of insider itineraries in the City of the Medici, so if you’re taking a trip to Florence this year check out our website or get in touch with our expert travel planners today!