When Michelangelo returned to the Sistine Chapel in his sixties, he faced the impossible task of outdoing himself. His ceiling had already reshaped the course of Western art — yet with The Last Judgement, painted across the chapel’s vast altar wall, he would go further still. Monumental, unsettling, and utterly revolutionary, the fresco plunged Renaissance Rome into a vision of cosmic reckoning: saints and sinners whirling through space as Christ delivers the final verdict. Michelangelo’s apocalyptic masterpiece would become one of the most audacious artistic statements in the history of art – and one of its most controversial. Discover its fascinating history with us.

Discover the Sistine Chapel

Join a Vatican Tour

“When the Last Judgement was uncovered, Michelangelo proved that he wished to triumph over himself in the vault he had made so famous, and since the Last Judgement was by far superior to that, Michelangelo surpassed even himself, having imagined the terror of those days, in which he depicted, for the greater punishment of those who have not lived good lives, all of Christ’s Passion.”

– Giorgio Vasari, The Life of Michelangelo, 1568

25 years after Michelangelo finally completed his era-defining fresco cycle on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, the artist returned to the Vatican Palace to take on an equally challenging commission. The year was 1533 and the ailing Pope Clement VII, mindful of his desire to make a mark on Rome that would ensure his legacy in the centuries to come, prevailed upon the ageing painter to take up his brushes once again at the scene of his greatest triumph. The task? To paint an immense fresco that would cover the entire altar-wall of the chapel, the only surface that remained largely free of decorations.

In truth, there were some frescoes already adorning the altar wall from Sixtus’ first decoration of the chapel. An altarpiece by Perugino was destroyed to make way for the new work, as were two images by him from the Moses and Christ cycles. For more on these pre-Michelangelo decorations in the Sistine Chapel, check out our article Botticelli, Perugino and the Wonders of the Early Renaissance in the Sistine Chapel).

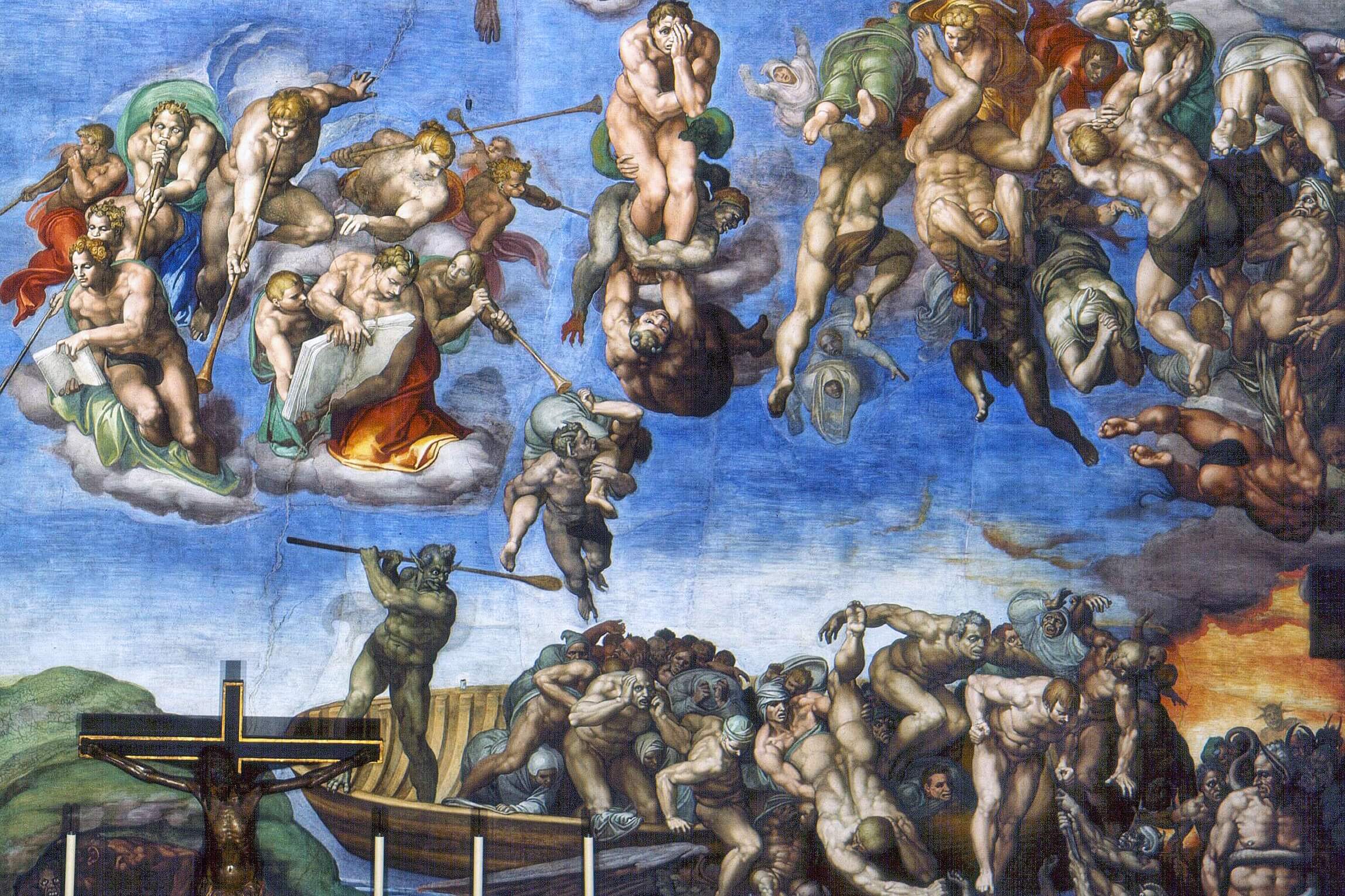

As with the ceiling, at first the proposition was unappealing to Michelangelo, who only agreed to take on the job when the subject matter was altered to befit his prodigious ambitions. Initially the painting was to represent either the Resurrection of Flesh at the End of Time or, according to Michelangelo’s contemporary Giorgio Vasari, The Fall of the Rebel Angels. What Michelangelo eventually came up with when he finally set to work in 1536 under Pope Paul III (Clement had died before the commission could go ahead) was much more complex, and elemental in the extreme: a dizzying, apocalyptic imagination of the Day of Judgement in which the saved are carried to heaven on the wings of angels, and the damned dragged downwards to hell and eternal torment by vicious devils.

And just like his ceiling decoration 30 years before, Michelangelo’s terrifying vision of salvation and damnation changed the rules of art once again. All of Rome stopped in its tracks when the altar-wall fresco was unveiled on October 31st 1541, as viewers gazed in awe at Michelangelo’s extraordinary technical skills and his unique ability to make even the hardiest observer tremble in awe. Whilst fellow painters and cognoscenti reportedly oohed and aahed at the virtuoso foreshortenings that only the great master himself was capable of pulling off, the pope was more concerned with the reckoning so vividly imagined before him. According to legend, when the pontiff gazed up at the completed fresco for the first time he fell to his knees, exclaiming “Oh Lord, charge me not with my sins when you come on the Day of Judgement.”

Michelangelo’s vast, complicated and frequently terrifying painting was in lockstep with the times. Not long before, Rome had suffered one of the most traumatic events in its history, when the city was sacked in 1527 by the unruly soldiers of Emperor Charles V: more than half of its population was slaughtered in a few days of horrific bloodshed, the waters of the river Tiber choked with unimaginable piles of corpses. Many saw the disaster as a divine punishment for Rome’s iniquities, and the sombre tone of Michelangelo’s painting begun just a decade later seems to reflect something of the repentant atmosphere that pervaded the city in those turbulent years.

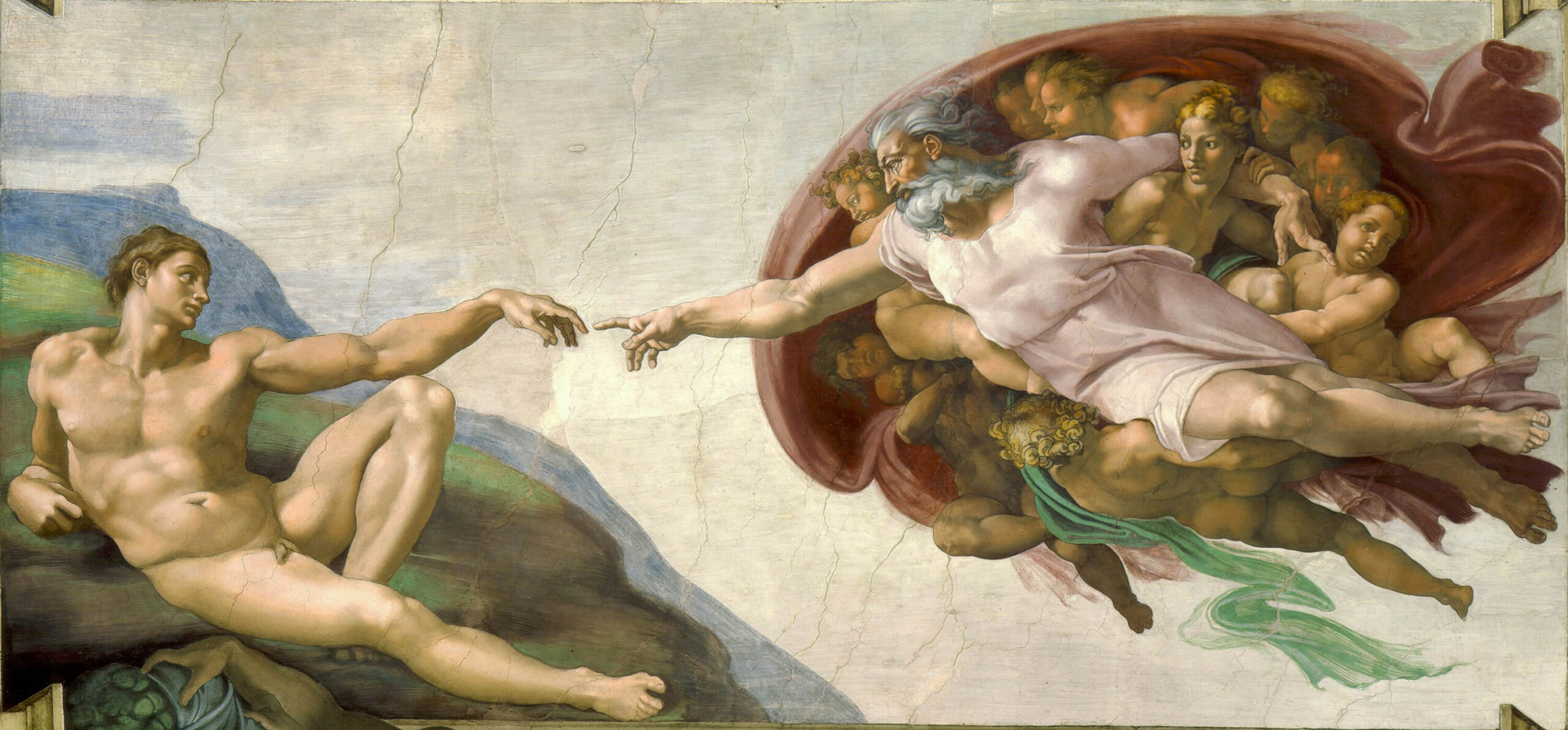

At the centre of the massive composition is Christ in the guise of a Judge, seemingly modelled on a monumental ancient sculpture such as the recently rediscovered Apollo Belvedere. At once impassive and seemingly hell-bent on retribution, Christ raises his right hand and imperiously damns the souls of the sinful with a single swish of his palm even as he simultaneously draws the spirits of the saved upwards towards their eternal abodes in heaven. The Virgin Mary cleaves closely to her avenging son, apparently in awe at his divine power.

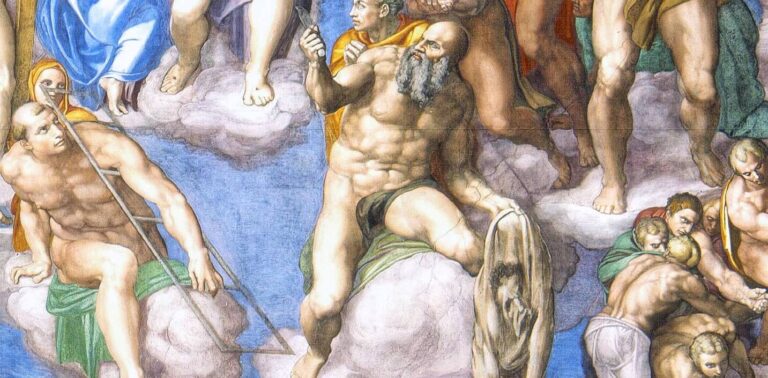

Surrounding Christ are the naked bodies of Christian saints and martyrs. The details are incredible, and you could spend a week in here trying to work them all out: perhaps the most fascinating however relates to the artist himself. A massively muscular St Bartholomew clutches his own lifeless skin, a reference to his being flayed to death by his persecutors. The flaccid fleshy sack conceals an amazing secret self-portrait – the sagging lifeless features are those of none other than Michelangelo himself.

Towards the bottom of the painting Charon, mythological ferryman to the underworld, hustles the latest denizens of hell to their final destination, threatening those unwilling to enter with his oar. Just above this is one of the most powerful details in all of art: a naked man is being dragged down through the clouds and towards eternal damnation by a pair of gleeful devils who chew viciously at his flesh. As the awful reality that he has been damned by the Judgement of Christ dawns on him, he clutches his face in his hands and his features are contorted into an image of pure despair. Others are luckier, and are being winched up to heaven by the hands of angels, ready to take part in the paradise promised to them by God for leading good lives on earth.

To contemporaries for whom the prospect of heaven and hell were very vivid realities, the message of the great painting could hardly be more powerful. Nor would it be lost on those who gazed upwards at the scene of judgement that this was the Pope’s private chapel, the man God had delegated to take care of his affairs on earth. Sure, only God can damn or pardon for all eternity, but in the here and now the Pope had absolute power of life and death over all his citizens.

The heaving mounds of naked bodies were intended by Michelangelo to demonstrate the perfection of God’s creation, but the fresco’s nudity was controversial from the outset. A number of conservative critics complained that Michelangelo was more concerned with showing off his own artistic genius than he was with expressing a religious message. Pope Paul III’s own master of ceremonies Biagio da Cesena complained that it was disgraceful for the pope’s private chapel to contain so much shameful nakedness, and argued that Michelangelo’s decorations were more fitting for a whorehouse than the centrepiece of the Christian world.

For Michelangelo this was unforgivable slander – he was a devout man, convinced that the naked human form was the clearest expression of God’s divine hand at work in the world. And so he retaliated in a way that was as effective as it was ingenious. Amongst the ranks of the damned who are being dragged towards the eternal torment of hell at the bottom of the painting he added a final figure. Minos, the judge of the underworld in classical mythology, appears with the ears of a donkey, entangled in the coils of a snake who gnaws at his genitals. To contemporaries the face of this latest addition was unmistakable: Biagio himself. Biagio appealed to the pope to force Michelangelo to remove his portrait, but to no avail: the pope explained that had the artist placed Biagio in purgatory he could have intervened, but his jurisdiction unfortunately didn’t extend to hell.

But as the cultural climate in Rome grew more conservative in the wake of the Reformation and the Catholic response in the Counter-Reformation, Biagio’s position was given much greater credence. Artworks like Michelangelo’s came to be seen as symbols of all that was wrong with a worldly church, and were ripe targets for Protestant criticisms of Catholic excess. Closer to home, the poet and satirist Pietro Aretino rehashed Biagio’s censure, scurrilously imagining that saints Blaise and Catherine were committing a lewd act and declaring that even brothel-dwellers would blush at the sight of the Last Judgement – quite a claim given Aretino’s role as the Renaissance’s most prominent pornographer.

Hypocrisy notwithstanding, the die was cast for the nude saints. Determined to clean up the act of renegade artists playing fast and loose with Christian values and theological accuracy, Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti attacked Michelangelo’s Last Judgement in his influential Discourse on Sacred and Profane Images published in 1582. Pope Paul IV, meanwhile, notorious for allegedly castrating ancient statues in the Vatican collections, was on the verge of having Michelangelo’s masterpiece whitewashed. Thankfully his proposed act of cultural vandalism never materialised, and a compromise was reached under his successor Pius IV, who had Michelangelo’s friend and protégé Daniele da Volterra veil the saints’ unmentionables with loincloths and draperies the year after the old master’s death.

Daniele was taken to task for his modifications in the centuries to come, and he was soon dubbed ‘Il Braghettone’, or the breeches-maker – but the truth is that he rescued Michelangelo’s work from a far worse fate with his relatively unobtrusive – and reversible – draperies. When the fresco was restored in the 1990s the coverings were mostly removed, revealing the muscular saintly bodies once again just as nature – and Michelangelo – originally intended.

Ready to visit the Sistine Chapel?

Book Your Tour Here!