Revised and Updated 31 January 2025

When you come to Rome, there are certain places that you simply can’t afford to miss. Magnificent St. Peter’s basilica – venerable centerpiece of the Catholic faith and the world’s ultimate Christian pilgrimage destination – figures right at the top of the list. But with Jubilee celebrations bringing more visitors and pilgrims to the Vatican in 2025 than ever before, you'll need to plan ahead. Find out how with us!

What is St. Peter's Basilica?

St. Peter's Basilica is visible from all across Rome

St. Peter's Basilica is visible from all across Rome

The current St. Peter's Basilica (built over an original 4th-century church) was one of the grandest construction projects ever attempted in the Renaissance, taking over 120 years to complete when it was finally consecrated in 1626. At over 190 meters long and with a dome that soars fully 136 above the floor, it’s still the largest church anywhere on earth, capable of holding 60,000 worshippers at once.

But whilst size matters, it’s not everything. St. Peter’s is also chock-full of artistic masterpieces by artists of the caliber of Michelangelo, Bernini and countless others. No story of Western art can be told without a visit to St. Peter’s, and the basilica can lay a strong claim to being the most spectacular church in existence.

It’s a good bet that you will be visiting St. Peter’s when in Rome; but with so much history to absorb and so many artworks to admire, the massive church can be overwhelming for the first time visitor. To get you started on the right foot, we’ve put together this guide to the history of St. Peter’s.

Read on to discover everything you need to know before you go!

Origins: Nero, A Fisherman and the Great Fire

The Crucifixion of St. Peter is the key moment in the story of the church

The Crucifixion of St. Peter is the key moment in the story of the church

The story of St. Peter’s Basilica goes all the way back to the time of the Emperor Nero, and the notorious fire that razed Rome to the ground in 64 AD. Seeking a scapegoat for a devastating inferno that he may well have started for his own ends, Nero hit upon the idea of blaming the eccentric and widely mistrusted new religious sect known as the Christians. You can learn more about the megalomaniac Nero and his tyrannical reign by visiting the extraordinary Domus Aurea, or Golden House of Nero - one of our favourite things to do in Rome.

The unscrupulous emperor ushered in a wave of persecution, and hundreds of members of the upstart religion were tortured and crucified in the Circus of Nero. Circus means racetrack in Latin - you will probably encounter the largest ancient racetrack of all when in Rome, the Circus Maximus - but alongside the usual business of breakneck chariot races, the cruel tyrant decided to add some blood sport to the entertainment. The location of Nero’s Circus? Across the river to the north-west of central Rome on the Vatican Hill.

Amongst the Christians executed in the Circus was one of Christ’s oldest companions, a certain fisherman from Bethsaida by the name of Peter, whom Jesus himself had anointed as the spiritual leader of the new faith. Peter requested that he be crucified upside-down as he considered himself unworthy to emulate the Messiah’s own crucifixion on Golgotha 30 years prior. The Roman authorities agreed, and Peter met his end with his eyes inches from the earth of Circus.

The site of St. Peter’s martyrdom soon became an important place of worship for the clandestine Christian community, and soon after the emperor Constantine finally legalized Christianity in the year 313 AD, a great church was built over the apostle’s tomb with the Emperor’s blessing. For the full story of the rise of the Vatican, see our detailed history of the Vatican here.

For over a millennium Constantine’s great basilica stood as the epicenter of Christianity, drawing Christians from across the world to Rome. The centuries inevitably took their toll, however, and by the opening years of the 1500s the church was in a state of terminal decline, slowly sinking into the foundations of the ancient circus.

Renaissance Renewal: Bramante and New St. Peter’s

The extraordinary interior of St. Peter's

The extraordinary interior of St. Peter's

Despite many influential voices calling for the Constantinian basilica to be repaired on account of its spiritual and historic importance, the ambitious Pope Julius II - whom you might know as Michelangelo’s patron in the Sistine Chapel – decided that the only thing to be done was to build a massive new state-of-the-art church on the same site. Sparing no expense, Julius entrusted the enormous responsibility of designing Christianity’s most important edifice to Donato Bramante, the father of High Renaissance architecture.

Julius and Bramante died within a year of each other however, and the architect’s controversial plan for a domed, centrally-planned building (that is, in the form of a cross with equal length arms) inspired by the Pantheon was put on ice.

Various illustrious Renaissance artists and architects, including Raphael, proposed designs to complete Bramante’s church, but the devastating Sack of Rome in 1527 meant that little progress was made for decades. In 1547, Pope Paul III surprisingly made the aged Michelangelo supervisor on the project, at the grand old age of 71. The decision proved to be a masterstroke.

Michelangelo Makes His Mark

The dome of St. Peter's is jaw-dropping

The dome of St. Peter's is jaw-dropping

Michelangelo only took on the job only with great reluctance and after much grumbling, disdaining the plans of his predecessor Antonio da Sangallo. He soon set about entirely revising the plans for the church, and it’s to Michelangelo that we owe the basilica’s distinctive undulating interior and the massive dome crowning its center – still the world’s tallest, half a millennium later.

Michelangelo took inspiration from the two greatest largest domes in Italy at the time - the ancient Pantheon in Rome and Brunelleschi’s Renaissance Duomo in Florence - to come up with an elegant double-shelled construction that was capable of supporting the massive dome, which weighs in at an eye-watering 40,000 tonnes. The dome rises 136.57 meters, or 448 feet, over the floor of St. Peter’s basilica, and is supported by four mighty piers each fully 120 meters tall.

The new church took over 150 years to complete, and Michelangelo too died before the work was done. The basilica was given its final shape by Carlo Maderno, who added two more bays to the church in order to transform it into the shape of a more theologically resonant Latin cross and designed the facade.

Giacomo Della Porta was the final architect to have a hand in the work, finally completing the dome in 1590. If you want to see what Michelangelo’s church would have looked like in its entirety, keep an eye out for a fresco of the proposed project in the vestibule of the Vatican Library as you are making your way to the exit of the Vatican Museums from the Sistine Chapel.

A popular urban legend recounts that the Lateran Pact (the agreement between the church and the Italian state that brought the Vatican City into existence) forbids any buildings that reach higher than Michelangelo’s cupola to be built in Rome; whilst the oft-repeated claim has no basis in fact, it does seem something of an unwritten rule that St. Peter’s remains the reference point for any construction projects in the Eternal City, and to this day it remains the city center’s highest point.

Bernini in St. Peter’s Square

St. Peter's Square is especially beautiful at night

St. Peter's Square is especially beautiful at night

The last great architect to make an important contribution to St. Peter’s was the Baroque master Gianlorenzo Bernini, who constructed the famous colonnade that frames the piazza outside the church. Here two lines of massive columns swell outwards to seemingly embrace the waves of pilgrims that come to pay their respects at the tomb of St. Peter in an extraordinary piece of urban planning.

At the center of the piazza is a massive 40-meter-tall Egyptian obelisk brought to Rome in 37BC, re-erected in front of the basilica in the 1580s in an incredible feat of early-modern engineering. For centuries it was taken as common knowledge that a golden orb atop the ancient obelisk contained the ashes of Julius Caesar himself. To everyone’s disappointment, when the globe was opened during the 1580s operation it was found to be empty.

Will the 2025 Jubilee Affect Visiting St. Peter's?

Expect large crowds at St. Peter's for the 2025 Jubilee

The 2025 Jubilee celebrations makes this year a very exciting time to visit St. Peter's, which will be at the epicenter of all the action. While the atmosphere will be incredible, this will also make visiting St. Peter’s Basilica much more crowded than usual, as millions of pilgrims flock to Rome. Expect longer security lines, restricted access on major event days, and possible closures for papal ceremonies. Planning ahead is crucial - consider booking a guided tour for priority entry and expert insights. That way, you won't have to worry about unexpected disruptions putting a spanner in the works!

What to See in St. Peter’s Basilica

Michelangelo's Pieta is one of St. Peter's must-see highlights

Michelangelo's Pieta is one of St. Peter's must-see highlights

To decorate the vast new church, many of the finest artists of the Renaissance and Baroque eras contributed artworks to the interior. Amongst the highlights to look out for in St. Peter’s are Michelangelo’s wonderful Pietà and a series of masterpieces by Gianlorenzo Bernini: these include the soaring bronze baldacchino at the center of the church marking the site of St. Peter’s grave, a massive sculpture of St. Longinus, the Cathedra Petri or St. Peter’s Chair, and the tomb of Pope Alexander VII.

These artworks are only the beginning, however. To find out what you need to see, check out our separate guide to the highlights of St. Peter’s basilica.

Climbing St. Peter’s Dome

The view from atop the dome is breathtaking

The view from atop the dome is breathtaking

If you are up to the challenge, then be sure to climb to the top of the dome and admire one of the best views in all the city. The climb takes place in two stages. The first involves ascending up the interior of the dome itself, offering amazing views down into the basilica and a close-up look at the mosaics that decorate it (practically invisible from the floor of the church far below).

If you want to reach even higher and you’re feeling fit, then you can keep going for another 320 steps right up to the very top of the cupola – the panorama over the city from the top has to be seen to be believed.

To find out how to climb the dome of St. Peter’s and what you need to look out for on the ascent, check out our guide to climbing the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

How to Visit St. Peter's and Skip the Lines

Visit St. Peter's in the early morning or at dusk

Visit St. Peter's in the early morning or at dusk

St. Peter’s Basilica is open from 7AM until 7PM each day. To avoid the worst of the crowds, we recommend that you time your visit either very early in the day (ideally before 8AM) or shortly before closing time. I must admit that I'm not much of an early bird, so you'll usually find me in the church around sunset. The light in the basilica at this time is particularly lovely.

Whatever you do, don't arrive in St. Peter's Square in the late morning or afternoon and expect to breeze in. This is even more true in 2025, as the Jubilee celebrations are bringing massive crowds of pilgrims to the Vatican. For a full guide to the Jubilee and what this means for planning your visit to Rome, see our dedicated guide here - Everything You Need to Know about the 2025 Jubilee in Rome.

Can I Visit St. Peter's alongside the Vatican Museums?

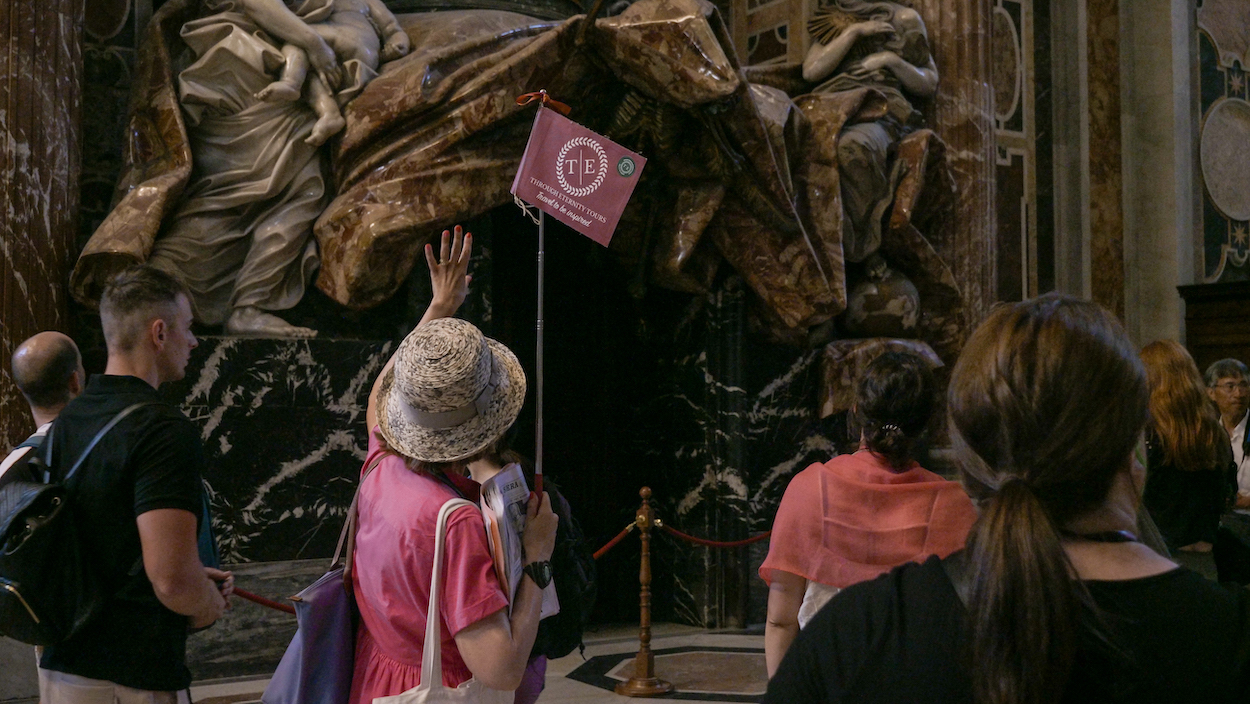

A guided tour is the best way to see St. Peter's

A guided tour is the best way to see St. Peter's

It’s likely that you will want to visit the Vatican Museums alongside St. Peter’s when in Rome. Usually you can’t enter St. Peter’s directly from the Vatican Museums – you will have to exit and then make your way around the walls to St. Peter’s square, where you’ll have to join the long queue. But if you take a special guided Vatican tour, you will be able to bypass this and reach the basilica directly from the Sistine Chapel via a special exit, skipping the lines.

Remember the dress code. If your shoulders and knees aren’t covered, you will be refused admission. So leave the hot-pants at home and bring a scarf or shawl. For more tips on how to make the most of your time in the Vatican City including the Vatican Museums, check out our practical guide to visiting the Vatican.

Now that you know all about the history of St. Peter’s basilica, you’re ready to visit yourself. Through Eternity Tours offer a range of guided tours of St. Peter’s and the Vatican museums – join us and experience the majesty of St. Peter's in the company of our friendly expert guides!

MORE GREAT CONTENT FROM THE BLOG:

- How to Climb the Dome of St. Peter's Basilica

- 7 Things You Need to See in St. Peter's Basilica

- What to See on a Dome Climb of St. Peter's

- Visiting St Peters and the Vatican Museums: A Practical Guide

- A Guide to the Vatican Gardens