The world's most famous sculpture, Michelangelo's iconic David is instantly recognizable. It's one of the first things that most visitors want to see on a trip to Florence, and for good reason. You can get an up-close look at Michelangelo's masterpiece on our tour of the Accademia in Florence, but if you want to learn more about the work before your visit, then read on!

In the world of Renaissance Florence, one man and one sculpture reign supreme. The biblical figure of David has long loomed large in the Florentine imagination. The story of the divinely ordained young shepherd who heroically defeated the brutal Goliath was one which struck a chord with the proud people of the Florentine republic, and Michelangelo's iconic rendering dominates the city's artistic landscape even today, more than 500 years after it was first unveiled.

Michelangelo’s masterpiece endured a long and difficult gestation. In the dying years of the 15th century, Florentines knew the massive slab from which it would one day emerge as if by magic only as ‘the giant.’ The enormous marble monolith had lain abandoned in the courtyard of the city’s cathedral for 30 years, its damaged stone frustrating any attempts to transform it from base material into a work of art - numerous were the artists who had tried and failed, tossing their chisels in despair at the impossibility of the task.

That was, until 1501, when the mighty Michelangelo arrived on the scene, returning from Rome to his hometown in order to fashion the block into what would become the most famous sculpture of Renaissance Italy, and an eternal symbol of the greatness of Florence. The anonymous marble giant had finally received an identity: David.

He towers before us haughty and provocative, muscularly confident in his readiness to vanquish his older and more powerful enemy. Michelangelo's statue soon became a powerful symbol of the ideals of the Florentine republic, leading it to be installed in central Piazza della Signoria rather than its intended location high up on the city's cathedral. Today the original is safely stowed away in the protective environment of the Accademia Gallery, although an in-situ copy still gives a vivid sense of how Michelangelo's David was traditionally located in Florence's most important public space.

But the great master’s muscular biblical hero isn’t the only David in town. Half a decade before Michelangelo set contemporary tongues wagging, early Renaissance master Donatello produced his own version of the shepherd boy made good. This David, bronze rather than marble, is no more than an effeminate teenager, lithe and androgynous. Hands on hips and nude apart from his helmet and boots, the hero has already dispatched his adversary, whose head lies at his feet. The challenging air of the later David is nowhere to be seen, possessing instead a melancholy sense of self involvement, the expression of very different times and sensibilities.

Commissioned by Cosimo de’Medici (known to history as Cosimo the Great) for the courtyard of his family palazzo, Donatello’s work was the first free-standing unsupported bronze cast of the Renaissance, as well as the first life-size nude to be sculpted since antiquity - an extraordinary technical and intellectual achievement that set the ground rules for much of what was to come in the fertile artistic world of quattrocento Florence.

Donatello's reputation as the greatest and most influential sculptor of the early Renaissance is undisputed, and testaments to his technical virtuosity are dotted all across the city. The forceful realism of early works such as the statues of Saint Mark and Saint George adorning the granary church of Orsanmichele for example seem to reflect the emerging values of a new canon of aesthetics. These works were commissioned and paid for by the city's powerful mercantile guilds, a reminder that artistic innovation in the Renaissance was powered by commercial interests as much as creative sensibilities.

Michelangelo's precocious technical skill too was a cause for wonder in his contemporaries. In the Casa Buonarotti - long-standing family seat of Michelangelo’s family and now a museum dedicated to the artist - stands one of Michelangelo's earliest and most original works, the marble relief depicting the Battle of the Centaurs.

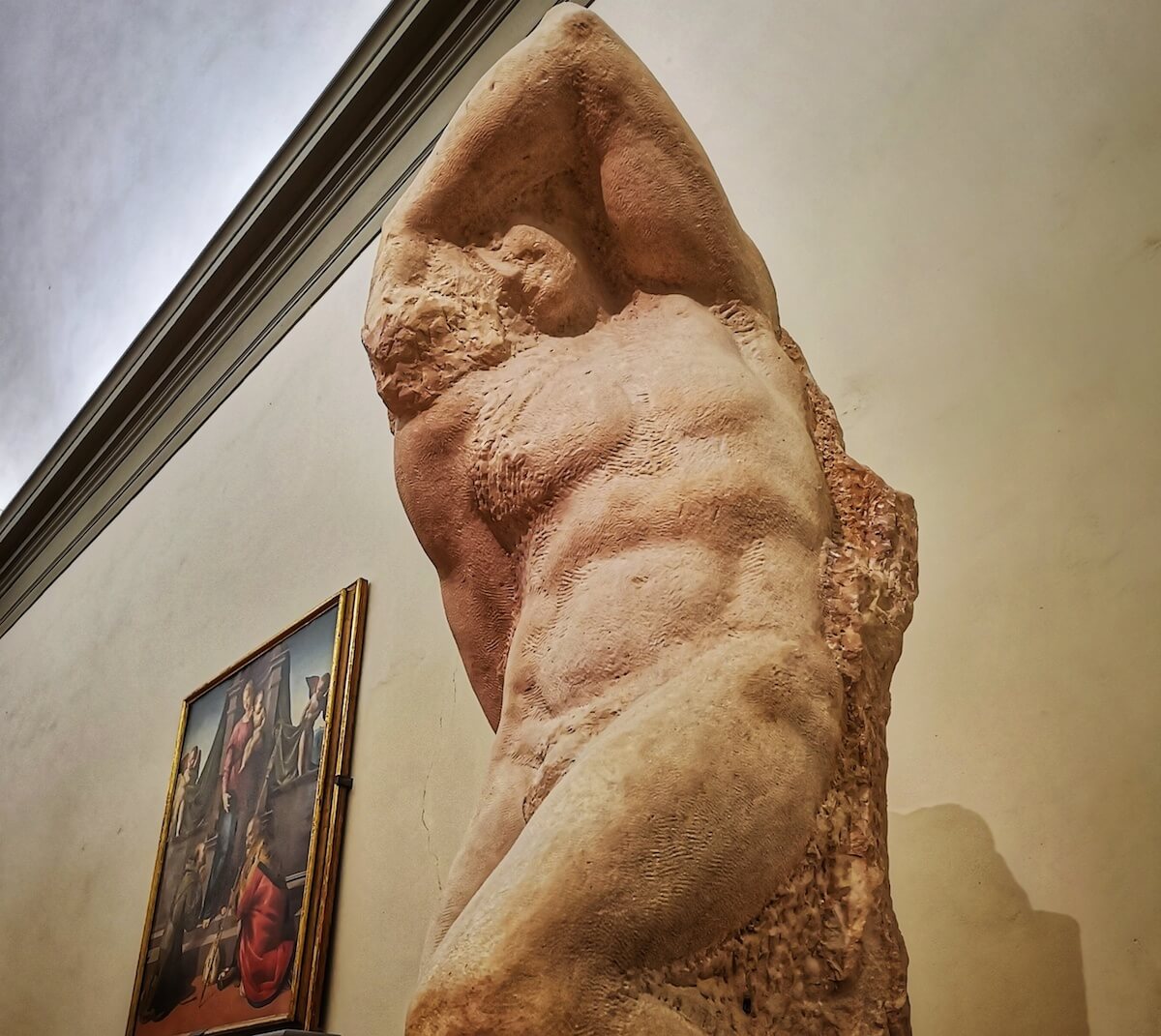

A confused and tortuous tangle of bodies and limbs emerge in various stages of completion from the rough stone in which they were imprisoned, awaiting the liberation of the sculptor's chisel; In this wonderful early statement of the artistic principles that would animate Michelangelo's work for the rest of his life, we can see the genesis of the fabulous unfinished Slaves of the Accademia, each struggling to be freed from their marble captivity: for Michelangelo, great works of sculpture always already existed in nascent form within the stone from which they would be carved - it was the task of the artist to allow them to emerge.

The artistic legacies of the two masters collide in the great church of San Lorenzo, right in the centre of the Renaissance city. In the 1460s, Donatello began work here on what would be his final works, the magnificent pulpits that grace the nave of the church. Elaborately decorated preaching pulpits had long been considered a fertile ground for sculptors - we need think only of the masterpieces created by Nicola and Giovanni Pisano in Siena and Pisa two centuries earlier - and Donatello’s relief sculptures adorning the Passion and Resurrection Pulpits are fascinating reflections of the dramatic register that the artist developed late in his career, far from the solid classicism of his earliest works.

In San Lorenzo’s New Sacristy nearby Michelangelo would take on the enormous task of constructing the Medici family’s mausoleum, a space that had to reflect the vast ambition of the city’s most powerful dynasty. Commissioned by Cardinal Giulio de Medici (future Pope Clement VII) in 1520, Michelangelo designed every aspect of the sacristy. The complex iconography that underpins the tombs of the Medici Dukes Lorenzo and Giuliano as well as the complementary statues representing Day and Night reflect the sophisticated philosophical environment cultivated by the Medici as well as Michelangelo’s own Neoplatonic spirituality.

Michelangelo's growing obsession with death rendered his art more idiosyncratic and expressive as his life wore on, and he began to seek a new expressive paradigm capable of conveying the profundity of his existential ruminations. In the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo we encounter what is perhaps the highpoint of this expressionistic sensibility in the magisterial Pieta that he intended to have adorn his own tomb. Leaving the tenets of naturalism far behind as an inadequate medium, Michelangelo's attempt to express the inexpressible was doomed from the start, and he abandoned the project in disgust. But in its rough and unfinished state the Florentine Pieta speaks of art's noble and impossible goals with a touching power that has rarely been matched.

There was, however, a precedent for Michelangelo’s deviation from the course of naturalism. Donatello himself had been driven to explore new modes of expression in his attempts to adequately reflect the range of human experience, and two of the most startling examples are housed just steps away from Michelangelo’s Pieta in the same museum. Here his emaciated and withered Penitent Magdalene is a completely unexpected exercise in artistic abstraction - Magdalene’s roughly hewn wooden surfaces signify far beyond the merely mimetic, and seems to be a natural progenitor to the experimental expressionism of 20th century sculpture.

Donatello and Michelangelo, Michelangelo and Donatello - there can be no understanding of the Renaissance, or indeed of Florence, without coming to terms with these two great masters whose lives and works were, and remain, inextricably intertwined. On our Florence walking tours we retrace their extraordinary legacies in the company of expert guides - join us to discover the masterpieces of Donatello and Michelangelo with us!