In an unremarkable room in one of Rome’s most overlooked museums hangs a small painting, scarcely more than two feet tall; from its present setting, most viewers who chance across this unassuming portrait would never guess that they are gazing upon what was once one of the most famous faces in Italian art. Like the more enduringly popular Mona Lisa, our portrait depicts a young woman enigmatically eyeballing the viewer. And, just as Leonardo’s image is today instantly recognizable, two hundred years ago it too possessed the mysterious power of an icon.

Best Rome Tours

Explore the Best of Rome

The Cenci: one of Rome’s Most Notorious Families

Beatrice was born into one of the most ruthless of the powerful families who fought for control of medieval Rome. Although Pope John X (914-28) was a Cenci, the family earned a reputation for fighting against the papacy, allegedly in the pay of external forces. In 1075, one Cenci kidnapped Pope Gregory VII just as he was performing mass at the altar of Santa Maria Maggiore; in 1398 another member of the family organized a plot to overthrow the papacy and murder Boniface IX. By the 1500s, their power and influence had decreased, but the family’s notoriety was soon to reach its peak thanks to the actions of its cruelest member: Francesco Cenci, Beatrice’s father.

Francesco had inherited a sizeable fortune, as well as the family’s sprawling complex of minor palaces on the edge of the Jewish Ghetto – only a short walk from Castel Sant’Angelo, where his daughter would one day be imprisoned and later executed. Rumors swarmed around Francesco, of his savage treatment of his servants and of the abuse he inflicted on his family members. Beatrice’s elder sister, Antonina, felt so terrorized by their father that she appealed to the Pope to allow her either to be married off or to join a nunnery – anything to escape her sadistic father. Several times he was accused of raping young women, one of whom he is alleged to have had killed after she refused his advances.

As Beatrice came of age, it was clear that she was a great beauty, full of grace and elegance despite the rough character of her family life. At the same time, Francesco was falling foul of the papal authorities and found it convenient to get out of Rome, taking up residence in a crumbling castle in the small countryside town of Petrella Salto in the mountains east of the city. He brought with him only his wife (Beatrice’s stepmother) and a few servants, leaving most of his dozen offspring to their own devices; the only exception was Beatrice. Ostensibly this was to protect the young beauty from the advances of Roman men, but many historians think Francesco may have had more vulgar intentions. In any case, Beatrice and her mother were shut in the castle, where they lived under virtual house arrest.

A Murder Most Foul…

On the morning of 9 September 1598, Plautilla Calvetti, the housekeeper of the Cenci castle and wife of its caretaker, was down in the village when she heard a loud commotion. When she rushed outside to see what was going on, a friend called to her: “Plautilla, Plautilla, they are screaming in the castle.” Rushing up the steep dirt-road towards the fortress, she saw Beatrice Cenci looking down from one of the windows; Plautilla called up to her but received no response. The young girl was staring into the distance, utterly silent; unlike her mother, whose frantic screams could be heard echoing inside the castle walls. As she continued up the road she met some men rushing down; “Signor Francesco è morto,” they told her: Count Francesco was dead.

His mangled corpse had been found in a wooded thicket at the base of the castle where the residents dumped their rubbish. Above, at the top story of the fortress, a wooden balcony had given way; the Count had fallen over forty feet to his death. An accident, or so it seemed. But as ladders and ropes were gathered to recover the body, questions began to arise: the hole in the balcony was too small, and seems to have been deliberately forced; the corpse was suspiciously cold. When the body was washed clean the truth became clear: large, jagged wounds covered Francesco’s temples, one large enough for a servant-girl to ghoulishly stick her finger inside. These could only have been the result of a violent blow; the Count had been murdered.

The criminal investigation, conducted by the Neapolitan authorities who controlled the region, soon uncovered the truth. Lucrezia, Francesco’s long-suffering wife, had given her husband a sleeping-potion, and after he had passed out signalled for two male accomplices. They entered his room where, despite being drugged, the Count awoke. They struggled with him, held him down, and smashed his head in with a hammer and chisel. Dumping his body over the wall into the thicket, they then broke apart the balcony to make it look like an accident. One of the two murderers was a hired hitman, the other none other than Olimpio Calvetti, caretaker of the castle and husband of Plautilla the housekeeper. He was also, it later emerged, the lover of the victim’s daughter Beatrice.

Or Vengeance Most Just

Beatrice and her mother were taken into custody; it was they, apparently, who were the real masterminds of the murder. The young Beatrice, it was alleged, had grown tired of her confinement, conspired with her mother and seduced the caretaker to enlist his help. We will never know what motivated Olimpio Calvetti; he died on the run, caught by a bounty-hunter who chopped off his head with a hatchet. The hired hitman didn’t make it to the end of the trial either, dying under torture in a papal prison. The trial of Beatrice and her mother lasted a full year, during which time the young girl never admitted her guilt, even under torture.

The case of the Cenci murder was the talk of the Rome. Given the details of the case and the evidence gathered, it seemed undeniable that Francesco’s wife and daughter had had a hand in his death, and in the complex codes of honour that governed early-modern Italy, patricide was the most loathsome of crimes. For a child to turn against her father was a deep betrayal that upset the fundamental order and morality of Italian society; it was clear that an example must be made. At the same time, however, other details emerged that made Beatrice a more sympathetic character. The Count had locked her in the castle, it was claimed, not to protect her from unwanted sexual advances but to make her vulnerable to his own. After enduring months of sexual abuse from her own father, how could anyone deny the girl her justice?

Public opinion in Rome swayed in her favor, but ultimately the rigidly doctrinaire papal court of Clement VIII ruled that, whatever the moral justice of Beatrice’s revenge, legal justice must be done: murder is murder. On 11 September 1599, on the banks of the river Tiber just outside the Castel Sant’Angelo, Beatrice Cenci and her mother, along with Beatrice’s brother Giacomo, were publicly beheaded.vThe bridge was apparently so crowded with onlookers that some fell into the Tiber and drowned as they jostled for a better view. Beatrice approached the executioner’s block with the utmost dignity, and succeeded in impressing the large throng who had gathered with her still intact beauty. One witness recorded, “The death of the young girl, who was of very beautiful presence and of most beautiful life, has moved all Rome to compassion.”

Beatrice Cenci: From Female Idol to Feminist Icon

One witness to the execution, it is claimed, was the renowned painter Guido Reni, who was long held to have painted the portrait of Beatrice that still hangs in the galleries of the Palazzo Barberini. An old legend recounts that the artist was able to visit her in prison, but a more likely story posits that Reni based his supposed painting on a glimpse he caught of Beatrice as she made her way to her execution through the streets of Rome. Indeed, the image of the young woman has a momentary quality to it, suggesting a fleeting instance and the emphemeral character of a young life cut tragically short.

It was this depiction of Beatrice that shaped her image in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Seeing it for the first time in 1818, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley declared that it possessed “a simplicity and dignity which, united with her exquisite loveliness and deep sorrow, are inexpressibly pathetic.” He was inspired by Guido Reni’s painting and Beatrice’s story to write a play based on the murder and her sad life, contrasting the sweetness and grace of Beatrice with the baseness of the events that surrounded her.

The painting, however, has had something of an identity crisis since Shelley’s day; its attribution to Guido Reni (who in any case was unlikely to have been in Rome while Beatrice was still alive) has become contested, with modern scholars preferring the authorship of Ginevra Cantofoli. So too, has the identification of its subject; the turban and drapery of the young girl are the attributes of a Sibyl, the female prophets of the ancient world who were a recurring subject of Renaissance painting. Of course, the artist – whoever they were – may have chosen to depict Beatrice in the costume of a Sibyl, but it’s equally possible that this image came to be associated with the story of Beatrice long after the dark events of 1599 had faded from the realm of historical memory and into the shadowy world of legend. If Cantofoli was indeed the artist, she was in fact only born 20 years after Cenci’s death.

Beatrice herself has also undergone something of an identity crisis. In Shelley’s telling, Beatrice is a victim, a blameless innocent whose purity of spirit and feminine virtue somehow remained intact despite the most violent and depraved suffering. More recently, however, she has been reappraised not as a passive victim but as a proto-feminist heroine, a young woman whose brave act of murder was a justifiable response to the rape and violence she had suffered at the hands of her own father – and by extension sixteenth century patriarchy. In this re-interpretation of her story, we should be thinking of an image not like the doe-eyed beauty of Reni’s painting, but rather something closer to Uma Thurman’s enigmatic avenger in Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill.

Although doubts have been cast on the “portrait” of Beatrice Cenci, another painting in the same museum can still claim a direct connection with our heroine. Although it seems impossible that Guido Reni could have attended her execution, another artist was almost certainly there: the great Baroque painter Caravaggio. He, it has been argued, had a prime view for her beheading by the Tiber, and bore witness to both her dignity in the face of death and the gruesomeness of the act itself.

Scholars have detected both of these qualities in a painting Caravaggio completed only a couple of years after Beatrice’s death: Judith and Holofernes. Here, the biblical heroine is beautiful but not entirely innocent as she murders the evil Holofernes in his sleep, in an echo (or foreshadowing) of Francesco Cenci’s own swift demise. The anatomical details and the spurting blood that shoots across Caravaggio’s canvas seem drawn from direct observation. Caravaggio’s femme fatale has a strength and a deliberateness missing in “Reni’s” portrait. Perhaps we find encoded here another sixteenth-century impression of Beatrice, not blameless but justified, not powerless victim but resolute heroine. In this reading, Beatrice Cenci represents not only a reminder of the ubiquity of male sexual violence throughout history, but a rallying cry to take up arms against it.

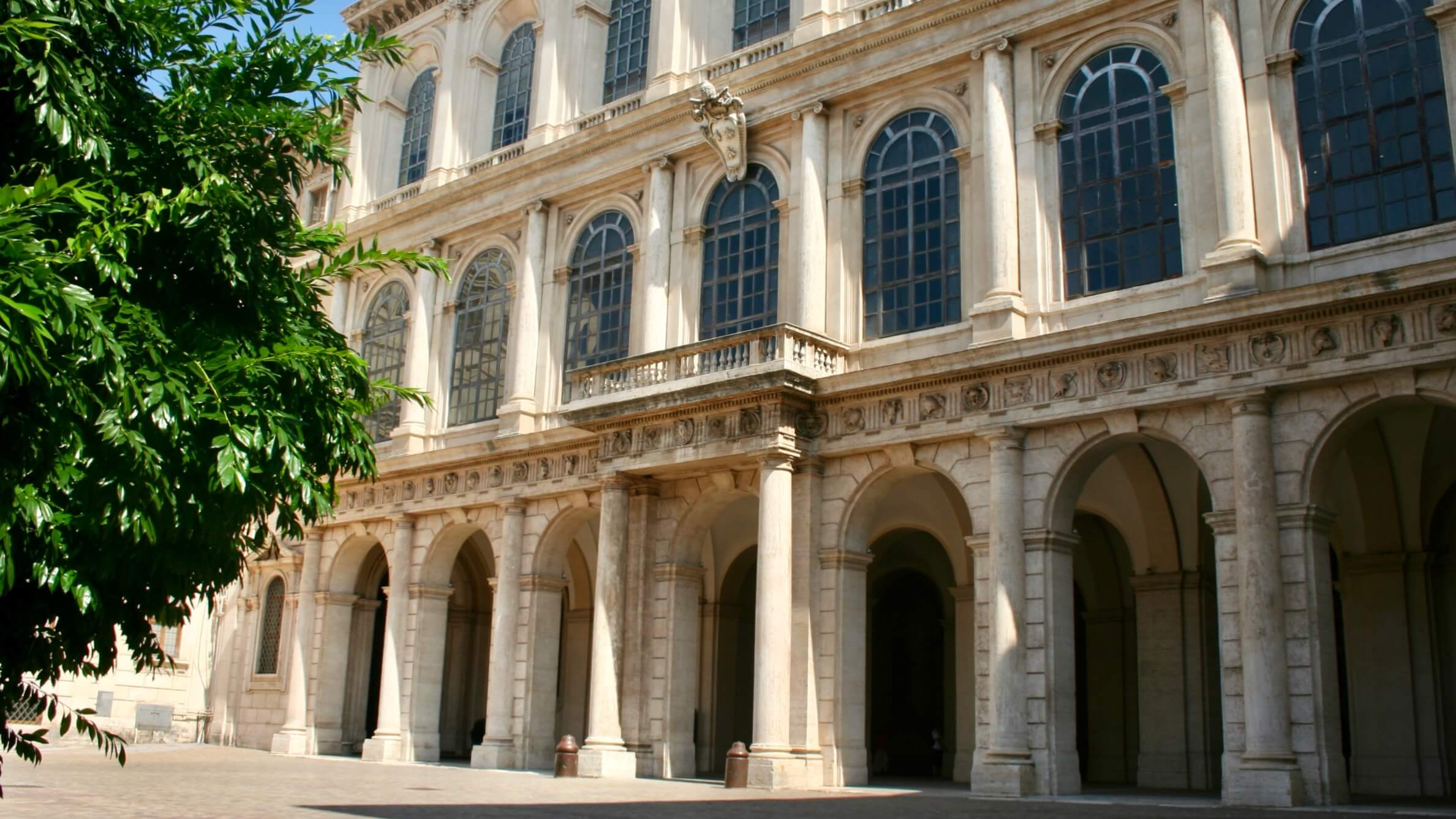

Beatrice Cenci is just one of the many tragic and inspiring characters you’ll hear about on our Secret Rome Tour. You can see her alleged portrait, as well as Caravaggio’s Judith and Holofernes, in the museum of Palazzo Barberini.

Book Your Rome Experience