Rarely in the history of art has a patron-artist relationship been as fruitful as that enjoyed by the young Gianlorenzo Bernini and the powerful Cardinal Scipione Borghese.

Bernini was one of those figures in history who seemed to be born for greatness. Through Eternity offers a range of Villa Borghese tours in Rome that allow you to explore the history of these two fascinating characters in greater detail.Get the full story below.

Baroque Rome Tours

Explore Rome's Finest Palaces

Destined to become the most famous sculptor of his generation and to forge the urban landscape of Baroque Rome in his own image, it was at the palatial suburban villa of Scipione Borghese that the young artist first found fame.

Entering the world on the 7th of December 1598 in Naples, where his Florentine father was a sculptor in the employ of the court, the family’s move to the Eternal City when Gianlorenzo was 7 or 8 might be one of the most important relocations in the history of art. Camillo Borghese had just assumed the throne of St. Peter as Paul V, and artists from far and wide flocked to Rome in the hope of his patronage of him. The well-respected if workaday Pietro Bernini was among their number, and he soon found work in the papal court.

Steeped in the workshops and building sites of Rome from an early age, the almost unbelievably precocious Gianlorenzo was already sculpting works when he was only 8 years old. Annibale Carracci was reportedly moved to remark that Bernini had reached a level of ability in childhood where most would delight to be at the height of their careers, whilst the art lover and future pope Maffeo Barberini warned Pietro that his son would soon surpass his master. Pietro’s immortal reply was that of a loving father – ‘it doesn’t matter, for in that case the loser wins.’

It was in the collections of the Pope’s powerful nephew, Cardinal Scipione Borghese, where Bernini would truly first flourish, the admiration of the refined connoisseur launching the still-teenaged Bernini on the road to stardom. Bernini would carve some of the most exciting, original, and daring sculptures that the world had ever seen in the Villa Borghese. His unique interpretation of ancient mythology and revolutionary conception of three-dimensional space ushered in a completely new language of art, launching the golden age of the Baroque.

Carved in 1618 when Bernini was still little more than an adolescent, this portrait bust of Pope Paul V, Camillo Borghese, showcases the artist’s early entry into the rarefied circles of Papal patronage. The tale of how Bernini first announced his precocious talent to the Roman art scene is one of the great artistic origin stories. His father had come to Rome to work on Papal commissions for the Borghese Pope, including his chapel at Santa Maria Maggiore, but the incredibly young Gianlorenzo made a bigger immediate impression in the rarefied circles of Roman connoisseurship.

Already the toast of great figures like Cardinal Maffeo Barberini (the future Pope Urban VIII) before he had reached his 9th birthday, the insatiably curious and ambitious Bernini reportedly spent three entire years of his childhood in the Vatican painting and sketching its collections, going to school on ancient sculptures like the Laocoon and Apollo Belvedere.

It was there that his personal acquaintance with the pope developed, for whom he carved this extremely expressive, austere portrait when he was just 19. The goateed pontiff stares at us blankly from pupil-less eyes, a commanding and somewhat unapproachable figure appropriate to his status as one of the world’s most powerful princes. He is dressed in vestments elaborately carved with the figures of Saint Peter and Paul.

Impressive as it is, especially given Bernini’s tender years when he carved it, the portrait of Paul V seems conventional and unremarkable compared to the works that the artist would create over the coming years for the Pope’s larger-than-life nephew Scipione.

A teetering, twisting tangle of bodies, the precarious Aeneas fleeing Troy is the first major work that Bernini would produce for the all powerful cardinal Borghese. The story comes from Virgil’s Roman epic The Aeneid, a tale that loomed large in the mythology of the Eternal City: according to ancient Roman mythology, as the hero Aeneas fled his native Troy at the denouement of the Trojan wars, the winds of fate took him towards Italian shores where he eventually founded Rome. The subject had a noble tradition in Italian art, with Raphael famously anachronistically depicting it in his Vatican fresco The Fire in the Borgo.

Bernini’s Aeneas is young and handsome, bearing a striking resemblance to Michelangelo’s Risen Christ in Santa Maria Sopra Minerva. In tow is his aging father, Anchises, clad in a rustic buncher, whom our young hero carries to safety on his sturdy shoulders, and his son Ascanius, who totters on dutifully behind.

The composition at first seems somewhat awkward, its towering serpentine form a not wholly successful take on Giambologna’s masterful Rape of the Sabine in Florence. But even though the young Bernini’s first attempt at a monumental narrative composition doesn’t entirely hit the mark, the virtuoso details are a hint at what’s to come: look out for the wonderful contrast between Aeneas’ taught and powerful figure and the stretched and sagging skin of his elderly father, who desperately clutches the household gods they have managed to salvage from their wrecked home in Troy.

The next large-scale mythological work that Bernini produced for Scipione marked a quantum leap in his development as a sculptor. In the Pluto and Persephone, created between 1621 and 1622, the young sculptor pushes the material limitations of marble to breaking point and beyond, working the unyielding stone as easily as if it were the most elastic dough. The ensemble also magnificently showcases Bernini’s developing ability to transform complex narratives into sculptural groups capable of telling entire stories in a single moment.

This extraordinary sculpture in the round tells the disturbing tale of Pluto, the dread god of the underworld, and the doomed Persephone, whose fates are locked in a dark tale of violence, lust, and abduction. Chancing to espy Persephone—the attractive daughter of the goddess of agriculture Demeter—cavorting in a meadow, the amoral Pluto determines to forcibly make her his wife at all costs.

Bernini takes up the drama after the god of the underworld has swept up the young Persephone in his meaty arms, already striding purposefully towards his subterranean kingdom as his victim struggles uselessly in his divine grip. Persephone pushes futilely against the bemused god’s greedily lustful face as an unseen wind whips her hair, her visage a horrifying portrait of terror and despair.

In one of the great virtuoso details of sculptural history, Pluto’s thick fingers sink into Persephone’s thigh, stony marble transformed into yielding flesh through Bernini’s preternatural skill. Only a trip around the entirety of the sculpture reveals the full gravity of the moment—revealed at Pluto’s feet is the three-headed dog Cerberus, guardian of the Underworld. Persephone has just been carried over the threshold of Hades, and there is no going back—her fate is sealed as unwilling goddess of death’s kingdom.

But as the myth goes there was at least some light at the end of the tunnel for the brutally abducted Persephone. Thanks to the imprecations of her mother, who refused to let crops bear fruit until she received justice, Persephone was allowed to return to the land of the living each Spring – heralding the growth and new life of the season. Persephone’s annual forced to return to Hades by contrast marked the beginning of winter, a moment forever immortalised in Bernini’s majestic marble.

It must have seemed to his contemporaries that Bernini had reached a level of perfection in the transformation of ancient mythological narrative into sculpture with Pluto and Persephone that would be impossible to match. And yet the young master was just getting started. Delighted as he was with the Pluto group, Cardinal Borghese decided to make a politically astute gift of it to the new pope’s nephew, Bernini’s bosom buddy Ludovico Ludovisi (the sculpture was only returned to the Villa Borghese in 1908). Scipione was convinced, it seems, that Bernini could go one better.

To replace the sculpture he had given away, Borghese commissioned Bernini to produce another mythological group, this time depicting the tale of Apollo and Daphne, recounted in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The myth tells how spiteful Cupid pierced Apollo with one of his arrows, making the god fall in love with the beautiful nymph Daphne. At the same time, he pierced Daphne with an arrow, causing her to detest the love-stricken Apollo, setting in motion a doomed dance of desire and repulsion.

Bernini once again takes up the action at its crucial moment. Apollo (whose features are inspired by the Apollo Belvedere in the Vatican) – young, handsome and clad only in a light cloak swirling about his body – is pursuing Daphne through the woods, their marble forms a whirl of speed and movement. ‘So ran the god and girl,’ Ovid writes, one swift in hope, the other in terror. The nymph is fleet of foot, but no match for the god ‘borne on the wings of love.’

Daphne feels her pursuer gaining ground, ‘shadowing her shoulder, breathing on her streaming hair.’ As we gaze on, we can almost feel the god’s hot breath on Daphne’s extraordinarily sculpted tresses. Desperate, Daphne implores her father, a river god, to save her from her fate: ‘ Oh help me, if there is any power in the rivers, change and destroy this body that has given too much delight.’

No sooner said than done: just as Apollo’s fingers close around Daphne’s waist, her body begins its bizarre transformation into a laurel tree. Her fingers sprout leaves, her toes take root, and her flesh transforms into bark. Her swift flight has been suddenly arrested in a moment of metamorphosis, to Apollo’s bewildered incomprehension. Daphne, for her part, looks back in mingled horror and surprise at the beginnings of her sudden transformation, no longer the beautiful woman she once was but not yet the inert tree she would become – a split-second captured and stilled for all time in Bernini’s extraordinarily fluid marble.

By the often horrifying standards of Ovidian myth, the story has something a happy ending. Apollo continues to lavish his love on the now well-rooted Daphne, embracing the branches and kissing the wood, caressing the bark under which he fancies he can still feel the faint beating of the nymph’s heart. Unable to possess Daphne, Apollo vows to make the laurel his tree and symbol and mandates that Roman victors will wear laurel wreaths in their triumphal processions in the times to come.

The choice of subject was audacious in the extreme: it had rarely been attempted in sculpture, the key metamorphic moment considered entirely unsuitable to the limitations of marble carving, a spatial art incapable of producing narratives relying on temporal development. But the young Bernini only saw opportunity where others saw problems, and succeeded in making his marble come alive, shifting the world of sculpture from the realm of space into the realm of time in a way that has perhaps never been equalled before or since.

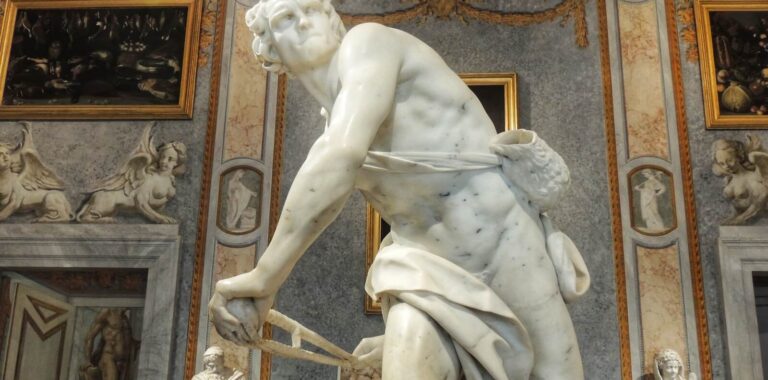

If the precocious Bernini was consciously taking on the challenge of Raphael in his earlier Aeneas group, the final epic narrative sculpture that he produced for Scipione Borghese saw him aiming his sights even higher in his attempt to fashion a place for himself in the top tier of Italian artists. The figure of the Biblical David slaying the seemingly immortal Goliath had already produced two of the greatest masterpieces ever essayed in sculpture: Michelangelo’s iconic hero contemplating the task ahead and Donatello’s triumphant, delicate youth resting on the giant’s freshly severed head.

In contrast to Michelangelo’s aloof hero or Donatello’s louche and charming youth, Bernini’s David is a solid, no-nonsense figure. Unlike the earlier Aeneas, David is far from a generic imitation of an earlier prototype and exudes individual personality. His furrowed brows bristle with intensity of purpose and he bites his upper lip in fierce concentration. Whilst Donatello and Michelangelo went for the moments preceding and succeeding the fight, Bernini went for the dramatic jugular. Here David is portrayed in the midst of his titanic struggle, poised to unleash the slingshot that will take down his fearsome enemy. And we seem to be caught in the crosshairs.

In a fantastic piece of site-specific invention, as the viewer enters the room in which David is housed, we quickly realize that he is launching an attack at an unseen figure behind us, placing us right in the midst of the action. Criticisms that Bernini has loaded David’s slingshot the wrong way round, whilst certainly accurate seem rather pedantic in light of the sculpture’s revolutionary inventiveness.

The David was to be the final large narrative sculpture that Bernini carved for Borghese, signaling an end to this first, glorious phase of his career. The sculptor’s friend and supported Maffeo Barberini, whom it was rumored held a mirror for Bernini to enable him to sculpt his own features into the face of David, had been elected Pope Urban VIII and was intent on making full use of his young protege. Bernini was soon to become the greatest court artist Europe had ever seen – but he perhaps never exceeded the magnificent lyrical works he created for Scipione Borghese in his airy Roman villa.

The vital energy of the man who gave life to the magnificent Villa and who had the foresight to see in Bernini an era-defining talent was captured with extraordinary vividness in two portrait busts sculpted by the artist in 1632, now at the height of his powers. Busy at work on the epic commissions ordered by Pope Urban VIII, this was to be the last work that Bernini would sculpt for his first great patron. And it is startling.

The marble features of the powerful and intelligent cardinal positively sparkle with a startling inner life and psychological depth: his penetrating gaze is clearly of someone used to being obeyed, whilst the subtle wrinkles of his plump face are extraordinarily realistic. Unlike the static and reverential portraits of an earlier age, Bernini seems to have caught Borghese in mid-speech, as if he’s just turned his head to make a remark.

To capture the true essence of the Cardinal, Bernini apparently adopted an entirely novel approach to preparation. Instead of having Borghese sit for him, the artist followed Scipione around in order to pin down exactly what it was that made the Cardinal unique, making off-the-cuff sketches of him in the process. Bernini’s dedication bore fruit, producing one of the finest portrait sculptures ever created.

The carving of this magisterial work wasn’t all plain sailing, however. As the bust neared its completion, Bernini discovered, to his dismay, that a flaw in the marble had appeared, running all across the Cardinal’s forehead. Undeterred, the artist set to work on a new version, which he completed in an extraordinarily short period of time.

Ever the showman, Bernini unveiled the first version to Borghese, who manfully strove to hide his disappointment at the disfiguring line across the head. At just the right moment, Bernini unveiled the second, unblemished version to the Cardinal’s undisguised glee since ‘relief is more satisfying when the suffering has been most severe,’ as Bernini’s biographer Filippo Baldinucci recounted. Today, the two works stand side by side in the Gallery, so you can compare them!

We hope you enjoyed our guide to the masterpieces by Bernini in the Borghese Gallery! If you’d like to admire these stunning sculptures in the company of an expert art historian, then check out Through Eternity’s private tour of the Borghese Gallery.

Rome Tours

See the Eternal City at its Best!