With masterpieces spanning every era and genre of art from magical medieval altarpieces to the avant-garde 20th-century experiments of the post-impressionists, few museums in the world can match the artistic riches of London’s National Gallery. The venerable Trafalgar Square institution is particularly strong on Italian Renaissance painting, and boasts works from the hands of practically every major artist from the 15th and 16th centuries.

This week on our blog we’re rounding up some of our favourites; although you could easily spend days in the National Gallery getting to grips with the Renaissance, from Leonardo to Michelangelo and Botticelli, we think these are a good starting point!

Best London Tours

Visit the National Gallery

1. Leonardo da Vinci

The Virgin on the Rocks, c. 1491-1508

Leonardo da Vinci is for good reason considered to be the Renaissance man par excellence, equally at home in the arts as he was in the sciences, happily mixing technological innovation with deep learning and a profound humanist spirit. London’s National Gallery is fortunate to be in possession of one of the artist’s most famous works, and one of the few large paintings by Leonardo’s hand to have survived to the present day. This is the Virgin on the Rocks, one of two versions of the subject that the artist would paint (the other is now in the Louvre in Paris).

The panel was originally intended as part of an altarpiece for the Milanese church of San Francesco Grande, commissioned by a confraternity dedicated to the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary. The composition features Mary surrounded by an infant Christ, John the Baptist and an angel, all apparently engaged in a profoundly spiritual but silent union: the baby Jesus raises his fingers in benediction as John the Baptist clasps his hands in awed prayer. Mary has one hand around the Baptist’s shoulder, whilst the other extends outwards from the picture plane in a virtuoso demonstration of perspective. The angel, meanwhile, captured in profile, is one of the most beautiful figures in all of art.

The tender, silent moment unfolds in a strange rocky landscape filled with minutely detailed plants, flowers and geological formations – evidence of the young Leonardo’s profound interest in the natural world. The landscape is suffused with a strange light that seems to make it extend infinitely backwards in space – this is thanks to the use of a technique known as aerial perspective, an innovation of Leonardo that would be widely adopted by Renaissance artists in the decades to come. Another revolutionary technique known as sfumato – in which colours are very gradually blended together to subtly blur contours – adds to the enigmatic nature of the scene.

2. Michelangelo

The Entombment, c.1501

Although widely regarded as the finest artist of his generation and perhaps any other, Michelangelo left behind very few panel paintings during his long career – only 3 can be securely attributed to the Renaissance master. This unfinished painting was originally intended for a funerary chapel in the church of Sant’Agostino in Rome, but lay abandoned when Michelangelo left the Eternal City for Florence in 1501.

With its insistent linear rhythms and flattening of 3-dimensional space, the daring composition seems to recall an ancient Roman frieze. The identities of the figures surrounding the central, lifeless body of Christ are difficult to ascertain with certainty; the androgynous figure on the left in a long orange cape is probably John the Evangelist, whilst the bearded old man behind Christ can be identified as either Joseph of Arimathea, who gave up his tomb so that Jesus could be buried there, or Nicodemus, who aided in his burial.

The three other female figures are probably the three Marys – Mary Magdalene, Mary Cleophas and Mary Salome, whilst the empty space on the panel’s bottom right was certainly reserved for the Virgin Mary herself. In its unfinished state it’s a disquieting, rather apocalyptic rendering of the events that will lead to Christ’s resurrection, and powerfully exemplifies Michelangelo’s sober religiosity.

3. Titian

Bacchus and Ariadne, 1520-23

Dazzling colours and incredible light effects are distinctive hallmarks of the Venetian master Titian’s mature style, and they are in full evidence in this canvas painted for the Duke of Ferrara Alfonso I d’Este in 1523. The painting formed part of a series of mythological paintings that were to hang in the Duke’s palace, and portrays the sizzling first meeting between Bacchus, the god of wine, and the princess Ariadne.

The story goes that Ariadne, daughter of King Minos, helped Theseus, king of Athens, to escape from the Minotaur’s labyrinth on the island of Crete. The two quickly became a couple, but just as quickly flighty Theseus abandoned Ariadne to sail off on new adventures. The jilted princess isn’t alone for long, however; soon after she stumbles across a fabulous procession of revellers led by Bacchus, returning from distant India. Bacchus is immediately struck by Ariadne’s beauty, and leaps headlong from his cheetah-drawn chariot to introduce himself. It’s love at first sight. The vibrant composition seems to pulse with life, and captures Titian at the height of his powers.

4. Sandro Botticelli

Venus and Mars, c.1485

In this playful scene, the radiantly beautiful goddess of love looks across at her nearly nude and out-for-the-count lover Mars, the usually formidable god of war. Mars is so deeply lost in sleep that he is oblivious to the three little satyrs cavorting around him, one of whom blows a conch into his ear. Mars’ undignified demeanour contrasts strongly with Venus, who is elegantly composed in a fabulous, diaphanous white dress picked out in golden trim. It seems that the lovers have been portrayed just after an amorous tryst, and the subject matter is wholly appropriate to the function of this painting, which was almost certainly commissioned to celebrate the wedding of a prominent Florentine family.

The distinctive ‘wide-screen’ format of the panel indicates that this was either the decorative front to a cassone, a type of chest that a wife would bring with her to her new life after marriage, or a spalliera, a decorative panel set into the wall of a bedchamber. The erudite subject matter demonstrates the extent to which 15th-century artists and patrons were turning to the classical world as sources of inspiration, a key tenet of Renaissance humanism

5. Raphael

Portrait of Julius II, 1511-12

The third member of the so-called ‘big three’ of High Renaissance art, Raphael was one of the art world’s first true superstars. The artist’s popularity was almost universal during his lifetime; handsome and eloquent in equal measure, the man known as the Prince of Painters left a string of masterpieces in his wake across Rome and beyond before a mysterious illness cut him down in his prime at the age of 37 in 1520.

In this portrait of Pope Julius II, Raphael immortalises his greatest patron, and perhaps indeed the the most important commissioner of art in the Renaissance: in addition to employing Raphael to paint the Vatican Stanze, Pope Julius also prevailed upon Michelangelo to undertake the herculean task of decorating the Sistine Chapel ceiling, thus setting in motion one of the most productive eras of art the world had even seen. Raphael’s extraordinary talents of expression are on full show in the way he vividly brings the fearsome Pope to life across the centuries.

Julius’ long beard and downcast expression reflect that this portrait was painted during one of the most difficult periods of his papacy – after losing control of the city of Bologna in a humiliating reverse in 1510, the bellicose pontiff known as the “Warrior Pope” resolved to not shave again until the city was recaptured; it took nearly two years of hard graft. When Pope Julius II died in December 1513, Raphael’s iconic portrait was publicly displayed in the church of Santa Maria del Popolo where it predictably caused a sensation, ushering in a new standard for papal portraiture in the centuries to come. Look out for the golden acorns that adorn the sides of the Pope’s seat; Julius’ family name was della Rovere, Italian for the oak tree from which acorns spring.

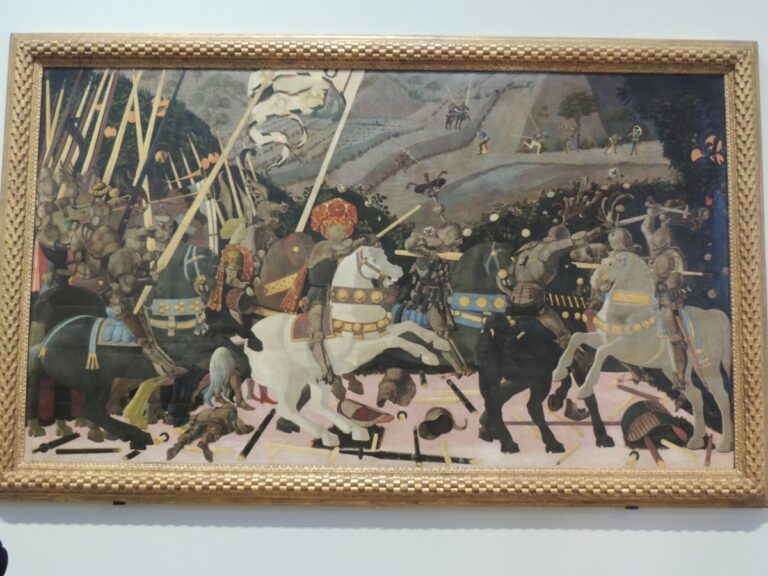

6. Paolo Uccello

The Battle of San Romano, c. 1438-40

The dark and violent side of the Renaissance is vividly on display in this enormous panel depicting one of the Florentine Republic’s greatest military victories. The battle of San Romano took place in the 1430s, and saw Florence take control of the route to Pisa in a protracted military campaign against their various foes. At the centre of the action is the dashing condottiere, or soldier for hire, Nicola da Tolentino riding into battle on a white charger, adorned in a truly extraordinary red headdress. Nicola would lead his troops to victory and be hailed as a hero in Florence soon afterwards.

Known to contemporaries as a somewhat strange and melancholic figure, the artist responsible for this geometric tour de force was Paolo Uccello, an artist who cut his teeth with the goldsmith Lorenzo Ghiberti on the project for the doors of the Florentine Baptistery, and whose paintings all demonstrate a powerful sense of 3-dimensional space no doubt influenced by these early experiments in sculpture. Uccello was also an expert in mathematics, and his grasp of the new science of perspective marked him out as one of the foremost innovators of his generation.

Perspective is king in this battle scene; the lances of the knights riding into battle in their fabulous suits of armour and the broken weapons littering the foreground provide the structuring principle for the painting. In the background, oblivious peasants go about their daily tasks in fertile fields bordered with orange trees and flowering hedges, a vivid reminder that war was an almost mundane part of daily life for European citizens in the 15th century.

7. Raphael

Saint Catherine of Alexandria, 1507

Much admired for her learning and heroic steadfastness in the face of persecution, Saint Catherine of Alexandria was one of the most widely venerated saints in medieval and early-modern Europe. According to her legend, Catherine was a 4th-century pagan princess who converted to Christianity at the age of 14. After converting a slew of state-sponsored philosophers sent by the emperor Maximian to convince her of the error of her ways, the enraged despot ordered Catherine to be subject to a horrifying series of tortures, including having her crushed on a spiked wheel.

The wheel broke thanks to an intervention from on high, killing her torturers instead. Although the saint was subsequently decapitated, it is the wheel with which Catherine is most commonly associated, and in this radiantly beautiful portrait painted by Raphael for an unknown patron the elegant princess leans on the failed device of torture. Catherine’s sinuous contrapposto and delicate features turned towards heaven reflect Raphael at his most elegant, and the figure would be highly influential on painters in the coming decades.

8. Titian

The Death of Actaeon, c. 1559-75

One of the final works painted by the Venetian master Titian, and left unfinished in his study at the time of his death in 1576, The Death of Actaeon depicts a dark tale of violence and punishment from the Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Ovid relates how the hunter Actaeon accidentally stumbles across the ancient goddess of the hunt Diana and her attendant nymphs bathing naked in a woodland spring. The furious goddess splashes Actaeon’s face before goading him to tell the world of his forbidden vision.

The terrified hunter flees, and Titian’s canvas takes up the action when he stops to slake his thirst in a stream. As Actaeon looks down into the water, he sees not his own face reflected up at him but that of a stag. The vindictive Diana, pictured firing her bow on the left of the scene, has transformed the hunter into his own quarry, soon to be mauled to death by his own hounds.

Titian’s dramatic canvas is a sequel to an earlier painting that depicted Actaeon coming across Diana and her nymphs, and forms part of a series of mythological paintings that the artist produced for King Philip II of Spain. This series, described by Titian as poesie because he considered them to be poems recast in painted form, is one of the landmarks of Venetian Renaissance art: Titian’s characteristically expressive use of colour and abstracted approach to form strongly differentiates his work from the harmonious compositions of his contemporaries in Florence and Rome.

9. Piero della Francesca

The Baptism of Christ, c. 1437

Piero della Francesca was one of the key figures in the development of a distinctively renaissance humanist idiom of painting in 15th-century Italy. The artist’s refined intellectual style was in high demand at the great courts of the Italian Renaissance; Piero worked for Sigismondo Malatesta in Rimini and Federico da Montefeltro in Urbino, for whom he painted some of his greatest panels – including the famous double portrait of the warrior prince and his wife Battista Sforza now in the Uffizi gallery in Florence.

Piero’s skills extended far beyond a preternatural ability with the brush; his mathematical genius allowed him to make extraordinary steps forward in the science of perspective, a method of convincingly rendering three-dimensional objects on the flat surface of a painted panel. Piero’s treatise De prospectiva pingendi, published in the 1470s, was the first detailed treatment of the subject by an artist, and this aspect of his art magnificently demonstrated in the National Gallery’s Baptism of Christ.

Originally painted for a church in his small Tuscan hometown of Sansepolcro, this highly ordered composition depicts Christ being baptised in the shallow river Jordan as other figures wait their turn by the water’s age and three elegant angels watch the proceedings. Look at how water droplets trickle into Jesus’ hair from the bowl held by John the Baptist, and at the virtuoso foreshortening of Christ’s feet. Everything depicted in the painting, from the large figures in the foreground to the distant hills, are all rendered in a single, coherently mapped space – testament to the giant leap forward in perspective made by Piero della Francesca.

10. Giovanni Bellini

Doge Leonardo Loredan, c. 1501-2

The majesty of Venice’s Maritime Republic is captured in all its pomp in this fabulous portrait of Doge Lorenzo Loredan, who ruled over the Serenissima from his election in 1501 to his death 20 years later. Although he gazes steadily out of the panel, his eyes are fixed somewhere beyond the viewer – probably on the serious affairs of state that were his constant concern. The identity of the sitter is made clear by the distinctive headgear he wears – known as the corno ducale, this exotic peaked bonnet was reserved for the Doge of Venice, typically only worn during official functions and events of state.

The elderly doge is decked out in robes of extraordinary finery, silken damask threaded with silver and gold all rendered with virtuoso precision by the painter Giovanni Bellini. Bellini was a member of Venice’s most influential artistic family – both his father and brother were famous painters in their own right, as was his brother-in-law Andra Mantegna – but Giovanni’s skill as a portraitist was unparalleled. In addition to the minute attention to detail Bellini pays to textures and surfaces, the sculptural three-dimensionality of the Doge confers upon him a startlingly life-like quality that departs from the formalised profile portraits common in 15th-century Venice.

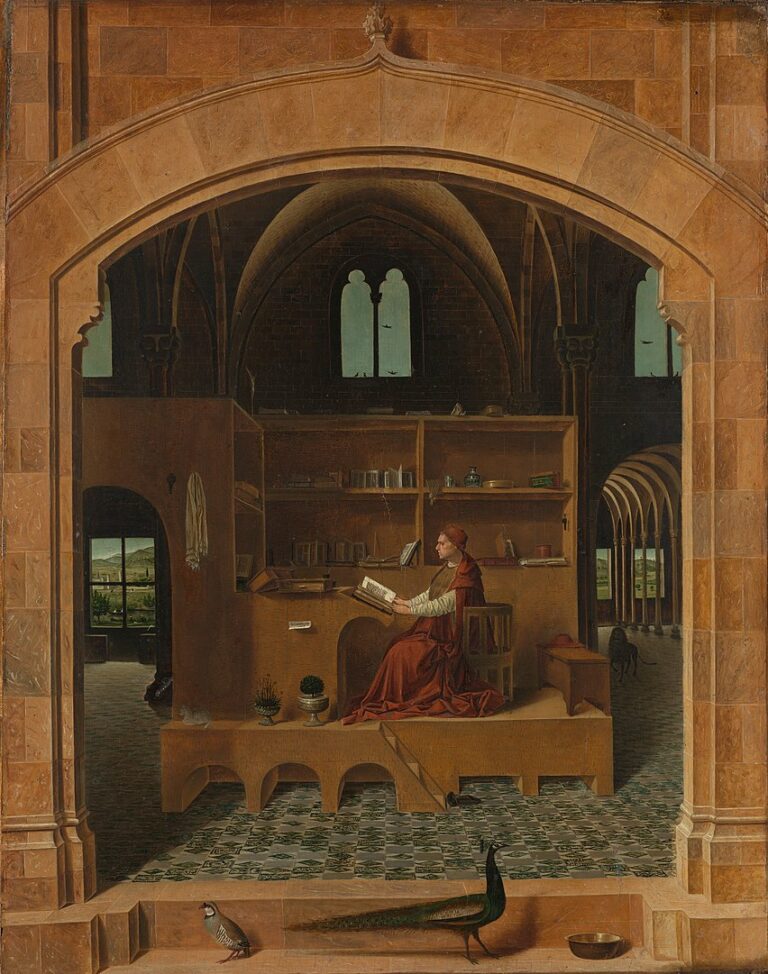

11. Antonello da Messina

Jerome in his Study, c. 1475

Historically credited as the man who introduced oil painting to Italy from northern Europe, Antonello da Messina was arguably the greatest Renaissance artist of southern Italy. Whilst modern scholarship has shown that Antonello was not in fact the first painter to utilise oil on the peninsula, he was certainly one of its leading exponents. Famous for his portraits and highly detailed cabinet paintings, Antonello’s luminous canvases recall the courtly Dutch tradition of Rogier van der Weyden and Jan van Eyck, whose paintings you can see in London’s National Gallery alongside this delightful miniature panel depicting the 4th-century church father and scholar Saint Jerome lost in thought in his study.

The innovative composition takes the format of cutaway view into the saint’s stage-like study, set into the cavernous space of a Gothic church. Everything in the scene is portrayed with incredible detail, from the books on the shelves to a garment hanging on a hook to plant pots lined up on the study’s ledge. Seen through an open arch that constitutes the painting’s fictional border, we seem to be privileged witnesses – or even voyeurs – into this private moment of reflection.

Apart from Jerome, the only other sign of life in the painting is a lion trotting through the arcaded interior; the story goes that one day the saint encountered a distressed lion in the desert struggling with a thorn lodged in his paw. After Jerome extracted the offending barb, the fierce creature refused to leave his side and became his constant companion – that’s why you will almost always see Jerome depicted alongside a lion in Renaissance art!

12. Carlo Crivelli

The Annunciation with Saint Emidius, 1486

Admired by contemporaries for his decorative style and eccentric visual touches, after serving a jail term in Venice for adultery in his native Venice Carlo Crivelli spent most of his professional life painting grand altarpieces for churches in the eastern Italian region of Marche. In these provincial surroundings far from the established artistic hubs of Venice, Florence and Rome, Crivelli developed a highly distinctive painterly idiom that is beautifully represented in this altarpiece depicting the Annunciation, originally created for a church in the Marche town of Ascoli Piceno in 1486.

Daringly, the biblical narrative unfolds not in ancient Jerusalem, but instead on the streets of a recognisably Renaissance town. The archangel Gabriel, beautifully decked out in multicoloured wings and flowing robes, kneels before the entrance to a fantastically grand palace as the great and the good of Ascoli Piceno through the city’s gridded streets. Within, the Virgin Mary kneels piously before a lectern reading the bible as the dove of the Holy Spirit swoops down from on high. Accompanying Gabriel on his important mission to bring tidings of Mary’s miraculous pregnancy is local saint Emidius, who clutches a detailed model of the town of which he is the patron saint. Ascoli was granted additional freedoms of self-governance from the Papacy on the feast of the Annunciation in 1482, explaining the importance of the feast-day to the city.

The vertiginous perspective of this street scene, the fabulous architecture, the luxurious fabrics and the focus on vivid ornamental details all combine to make this one of the highlights of Renaissance painting in the National Gallery. Look out for the gnarly marrow and apple illusionistically hanging over the edge of the painting and protruding into our space beyond the panel – this kind of witty visual detail is a classic Crivelli calling card.

Through Eternity Tours offer expert-led guided itineraries across London. If you’d like to visit the National Gallery in the company of one of our resident art historians to learn more about the Renaissance masterpieces featured in this guide, be sure to check out our Best of London Tour with the National Gallery.

Book Your London Experience