A few weeks ago on our blog we featured a guide to 10 of the most famous masterpieces in the British Museum. This time around we’re delving deeper into the magnificent collections of London’s largest and most important museum to bring you 10 fascinating lesser-known objects to look out for when visiting the British Museum. From one of the oldest representations of the human form ever created to lifesize Chinese terracottas, a glass cup that changes colour, Maya bloodletting rituals and more, read on for a whirlwind journey through world culture as recounted by these fascinating artefacts!

London Tours

Explore the British Museum!

One of the finest masterpieces of Mayan art, this limestone lintel carving was commissioned by the ruler of the Mexican city of Yaxchilan in the 8th-century to decorate an important building. The relief portrays the Yaxchilan king Shield Jaguar the Great participating in a rather gruesome bloodletting ritual alongside his wife Lady K’ab’al Xook, who pulls a thorn-studded rope through her tongue. The king lights the scene with a burning torch. Blood-letting rituals were common amongst Maya royalty, who considered themselves to be imitating the gods’ creation of humankind through a similar act of bloodletting. The rich costumes of the royal couple beautifully showcase the refined aesthetics of Mayan culture.

This striking and mysterious life-size female sculpture probably represents a Huastec mother goddess related to the Aztec deity Tlazolteotl, a figure associated with fertility, growth, vegetation, waste and purification. The Huastec people lived on the Gulf Coast of Mexico, and were conquered by their powerful and expansionist Aztec neighbours in the early 15th century. We know very little about them today, but this highly abstract figure with a tiny head and small breasts sporting a massive, fan-shaped headdress seems to bring this lost civilisation eerily back to life.

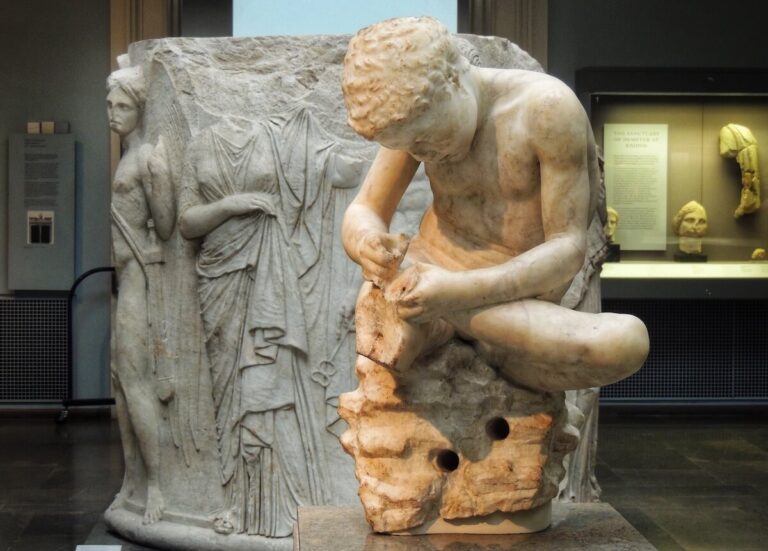

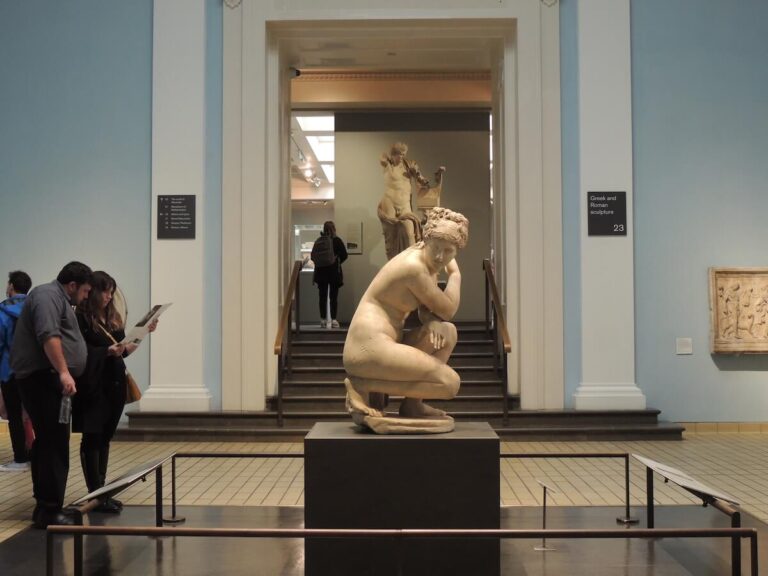

Crouching naked close to the ground, the ancient Roman goddess of love has been surprised at her bath. She covers her breasts with her hands as she looks over her right shoulder, presumably in the direction of the watcher who has disturbed her ablutions. Tracing its origins to a lost Hellenistic original, it’s one of the most famous poses in classical art, and versions of this statue recur frequently in antiquity.

The Lely Venus, as the sculpture in the British Museum is known, was carved sometime during the Antonine period, around 100 AD, and by the 17th century had made its way into the extensive collections of the Gonzaga dukes of Mantua. At the behest of the painter Peter Paul Rubens, King Charles 1st purchased the statue, and although on long-term loan to the British Museum iit remains in the Royal Collection to this day. The high degree of realism and 3-dimensional plastic form makes the Lely Venus one of the finest ancient sculptures on display in Britain.

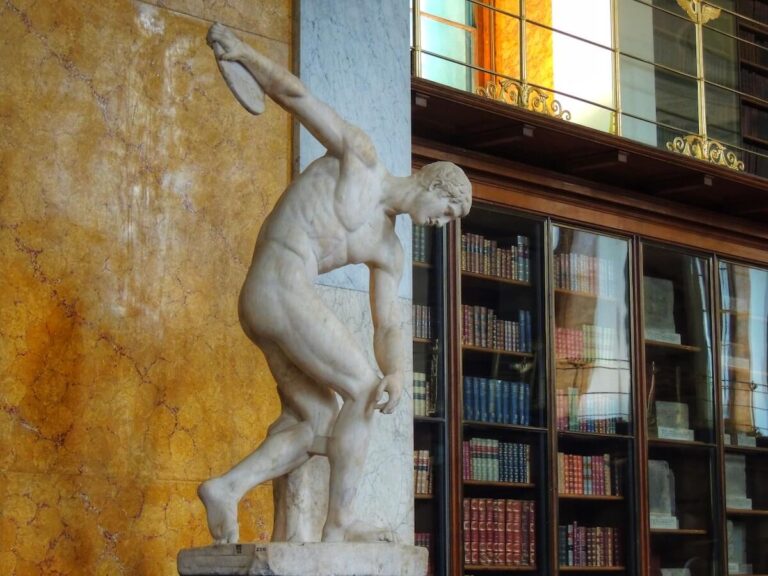

Nothing reflects ancient Greek ideals about the relationship between bodily form and cultural achievement more fully than ancient artworks depicting athletes in full flow. One of the most admired of all Greek sculptures was a 5th-century BC bronze depiction of a discobolus, or discus thrower by the artist Myron. Although Myron’s original bronze has been lost to the vagaries of time, numerous marble copies by the hands of Roman sculptors survive, including this version found in Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli just outside Rome.

The discobolus is in full control of his body and movements as he gracefully propels his discus, arms and legs in beautifully poised equilibrium. Found decapitated in the ruins of the Imperial villa, the head of the British Museum’s discus thrower was incorrectly restored in the 18th century – instead of looking downwards the athlete was originally portrayed looking back at the discus as he prepared to launch it into the sky.

This incredible Neolithic statue is one of the oldest representations of the human form in the world, dating from between 7,2000 BC and 6,500 BC. Found alongside a number of other statues at the archaeological site of ‘Ain Ghazal in present day Jordan, the sculpture is made from plaster covering a reed framework (long since decomposed). The most striking feature of the figure is his bright, staring eyes, made more luminous by outlining the irises with bitumen. It is not clear what the statues were made for, but it has been theorised that they were conceived as funereal objects designed to be buried as they were discovered carefully preserved in an underground pit where they had lain undisturbed for up to 9,000 years.

These highly expressive terracotta figurines come from ancient Cyprus, and were produced around 700 BC. With upraised arms extending from their schematic cylindrical bodies, it has been theorised that the figures are priestesses involved in the cult celebrations of a local deity. One of the figures still has her head, topped with an elaborate headdress. Dashes of paint add colour to the figures. Cyprus was considered to be the home of Aphrodite, goddess of love, in ancient Greek mythology, and the strategically important island in the heart of the eastern Mediterranean became a melting pot for the meeting of various civilisations in antiquity. These beautiful artefacts showcase the distinctive, abstract style characteristic of ancient Cyriot material culture.

This one-of-a-kind ancient glass drinking vessel changes colour depending on the light conditions; when light passes through the cup from behind it appears red, whereas if lit only from in front the glass appears green. This unique characteristic is down to the fact that the vessel is made from dichroic glass – a complex technique that requires microscopic particles of gold and silver to be suspended in the glass material during production. The exact production method is not well understood even today, and it is not clear just how intentional the technique was.

At any rate, very few artefacts in dichroic glass were made; in fact, the Lycurgus Cup is the only complete Roman object made from it in existence. Apart from its chromatic magic, the vessel is a beautiful object in its own right, with a decorative scheme representing the story of the mythical king Lycurgus in a cage-like outer shell. Roman cage-cups, known as diatreta, are considered to be the apogee of the Roman glass-maker’s art.

The female bodhisattva Tara is a significant figure in Buddhist mythology, and this masterful bronze statue of her is testament to the central role of the religion in Sri Lanka, where it was created in the 8th century. The sculpture was produced using the advanced lost-wax casting technique, before being gilded to a gleaming sheen that adds to the sensuousness of the figure. Tara’s voluptuous hour-glass figure is naked from the waist up, and despite the spiritual rather than erotic background of the sculpture – Tara would in all likelihood have been set up in a Buddhist temple – conservative norms in 19th-century Britain meant that Tara was not publicly displayed in the museum for over 30 years after its controversial acquistion from Sri Lanka in the 1830s. Today it is one of the highlights of the British Museum’s Asian galleries.

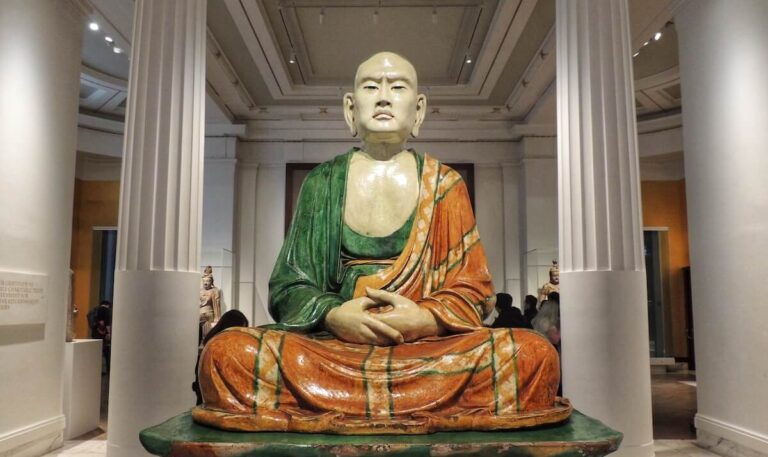

This magnificent life-sized sculpture depicts a Luohan, the Chinese phrase for a disciple of Buddha. Sculpted in a kind of glazed terracotta known as Sancai (three-colour), this Luohan, clad in vibrant green and brown robes, is seated with hands crossed on his lap. He stares outwards with a somewhat severe expression on his face. The sculpture was originally part of a set of 18 works crafted during the Liao dynasty (perhaps around 1200 AD, although dating remains controversial), probably originally intended for a temple in Beijing but moved to a mountain cave near Yixian. So lifelike are the features of these luohan that they have been theorised to portray actual portraits of important contemporary monks.

This massive snarling lion captured mid roar was one of a pair that guarded the entrance to a temple of the goddess Ishtar in the Assyrian city of Nimrud in northern Iraq. The temple was linked to the palace of King Ashurnasirpal II, who reigned in the 9th century BC. Lions were a popular animal amongst the royalty of ancient Mesopotamia, and are often seen guarding the gates of cities and temples in the region. Ishtar was one of the most important goddesses in ancient Mesopatamian cultures; associated with war, fertility and love, she is typically accompanied by a lion.

Through Eternity Tours offer expert-led guided itineraries through the colllections of the British Museums as well as many other sites in London. To find out more, check out the full range of our London tours here!

London Tours

Explore the British Capital!