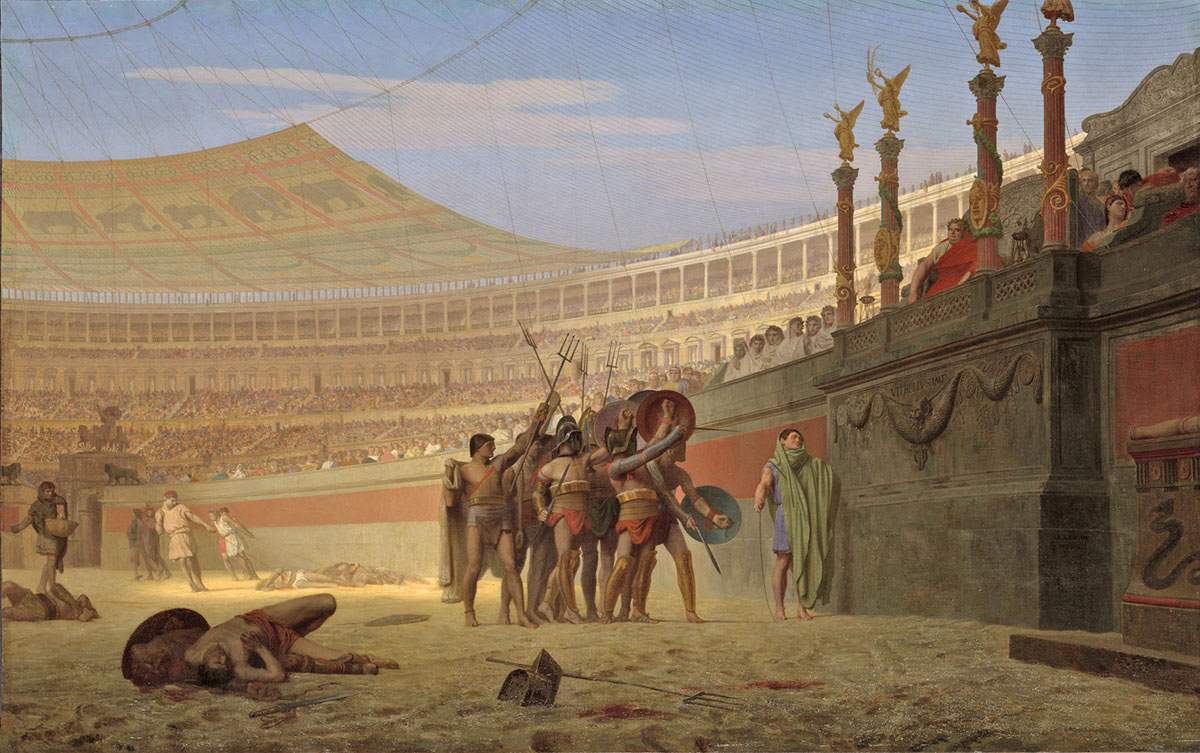

When in Rome, it goes without saying that visiting the Colosseum is an absolute must.

Nowhere else in the Eternal City provides a more spectacular and vivid window into the splendor that was ancient Rome. But there’s a lot more to this historic part of the city than just the Colosseum. The surrounding area offers a wealth of additional sights and activities that you should consider adding to your itinerary.

From ancient ruins to charming piazzas and wonderful hidden churches, we’ve curated a list of the top things to do near the Colosseum to help you make the most of your trip to Rome. Read on to discover what you need to see around the Roman Colosseum!

Rome Tours

Explore a Hidden Side of the Eternal City

No history of the Colosseum can be told without affording a central role to the vast Imperial palace known as the Domus Aurea, or Nero’s Golden House – and luckily it’s just a few minutes walk away. Built by Nero over the smoldering ruins of the city after a devastating fire reduced Rome to ashes in 64 AD, this gargantuan palace was almost unimaginably opulent, complete with 300 rooms and a rotating dining hall open to the stars of the night sky.

But Nero’s excesses were proving too much for the Roman populace, and it wasn’t long before the tyrant was forced to commit suicide. All traces of him were obliterated from the face of Rome, and the palace was buried by the engineering projects of the new regime – the most important of which was the Colosseum itself, built over the site of an artificial lake that was at the center of Nero’s palatial complex.

Much of the palace remained intact, however, hidden from the eyes of the world for centuries beneath the earth. These days it’s been excavated, and you can admire the incredible architecture and decorations of the hedonistic emperor’s home on a special limited-access tour that rounds out your understanding of the nearby Colosseum. Click the link below to find out more!

If the Colosseum was where ancient Romans came to let their hair down, the nearby Roman Forum was all business. This was the nerve center of the ancient empire – an area filled with important temples, courthouses, government buildings, shops, sweeping public squares and more.

It might seem like a confusing jumble of ruins today, but here you can really feel ancient history come alive like nowhere else – especially if you visit the Forum with an expert archaeologist. Evocative highlights include the Temple of Saturn, the Basilica of Maxentius and the House of the Vestal Virgins – check out our in-depth guide to what you need to see in the Forum here. It’s easy to let your mind run free here, conjuring the image of Julius Caesar confidently orating in the Senate, or Cicero strolling down the cobbled Via Sacra that ran down the center of the site.

Too often overlooked by visitors to the city en-route to the nearby Colosseum and Forum, the Palatine Hill is the third major site of ancient Rome’s archaeological complex.

This hill overlooking the valley of the Roman Forum is where the long history of Roman civilization began: Rome’s first settlement is believed to have been made here, a tale embellished and expanded in the mythological legend of Romulus and Remus. As Rome grew, the Palatine became one of the most well-heeled neighborhoods in the city, a leafy enclave far removed from the dust and chaos of the metropolis below.

During the Imperial era the all-powerful Roman emperors built their huge-palaces here, ruling over the ancient world’s greatest empire in the lap of luxury. The grand ruins of their palatial abodes still take the breath away, and no visit to the Colosseum is complete without a stroll around the Palatine!

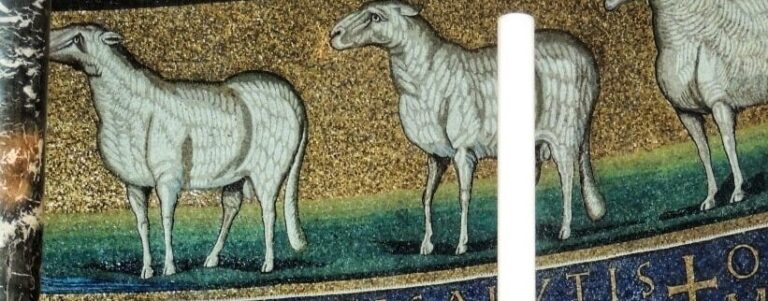

A short walk from the Colosseum down Via dei Fori Imperiali, the spectacular ancient church of Santi Cosma and Damian is built right into the fabric of the Forum itself. The church, dedicated to the Greek doctor brothers Cosmas and Damian, was founded in the year 527 by Pope Felix IV, and repurposed the architecture of the Temple of Peace and Temple of Romulus.

What makes it a must-visit in the Colosseum area are its amazing sixth-century apse mosaics, widely regarded as amongst the most extraordinary testaments to Christian late antiquity in Rome.

After a busy day exploring the Colosseum, Forum and Palatine Hill, you’ll no doubt be hungry – and thirsty! Ditch the tourist traps around the ancient amphitheater and make a bee-line for the nearby Monti neighborhood, just a 10 minute walk from the Colosseum. In antiquity this was ancient Rome’s most dilapidated slum, known as the Suburrah. But time changes everything, and these days it’s quite the opposite: a picturesque tangle of cobbled streets and pristine piazzas, charming cafes and great restaurants – the perfect place, in short, to take advantage of aperitivo hour!

The heart of the action is beautiful Piazza Madonna dei Monti, an always lively and atmospheric corner of the neighborhood filled with visitors and locals alike chatting, sipping and eating long into the evening.

Art lovers will not want to miss paying a visit to the church of San Pietro in Vincoli, a 5-10 minute walk away from the Colosseum. The reason? It’s here that you can admire the imposing Moses that Michelangelo carved for the tomb of Pope Julius II.

Forced to dramatically reduce the scale and complexity of the planned project, Michelangelo viewed the overall tomb as the biggest failure of his career; but the Hebrew prophet he created as its centerpeice remains a breathtaking masterpiece. Moses’ eyes seem to blaze with anger, and his intense expression embodies the famously irascible Michelangelo’s ‘terribilità’ – the unique power of his work to evoke awe and fear.

Michelangelo was reportedly so captivated by the figure that he implored the statue to come to life. When the seated prophet did not respond to his command to ‘speak!’, the frustrated Michelangelo struck the lifelike figure’s thigh with a hammer.

Another delightful church that’s free to visit near the Colosseum, the basilica of Santa Francesca Romana is hidden in plain sight atop the Roman Forum. A classic Roman palimpsest, the present church was constructed in the 10th century on the legendary spot where the pagan magician Simon Magus made the fatal decision to test his powers against the apostolic duo Peter and Paul.

The sorcerer’s levitation trick quite literally fell flat when the saints fell to their knees in pious prayer, sending Magus tumbling to his death. Various relics, mosaics and sculptures adorn the beautiful interior, which offers a welcome respite from the blazing sun and shade-deprived ancient city nearby. Take a peek out the church’s side door for a great view onto the Via Sacra and Arch of Titus.

When visiting the Colosseum, you’ll be sure to notice the large, impressive triumphal arch located in the piazza in front of the amphitheater. There can be few more vivid symbols of the power invested in the emperors of ancient Rome than the triumphal arches that once dotted the city: according to contemporary sources there were no fewer than 36 triumphal arches in Rome at the height of the Imperial era.

Edifices without any real practical function, the soaring tripartite arches were instead imbued with a purely symbolic power, constructed to celebrate the reigning emperor’s glorious military victories and role as protector and leader of the vast Roman Empire.

The most impressive triumphal arch still standing is arguably the Arch of Constantine, located in the shadow of the Colosseum and built by order of the emperor to commemorate his victory over his bitter rival Maxentius at the beginning of the fourth century AD. The wonderful bas reliefs that decorate the arch, however, were taken from earlier monuments and repurposed to celebrate Constantine.

Dive Deeper into Rome