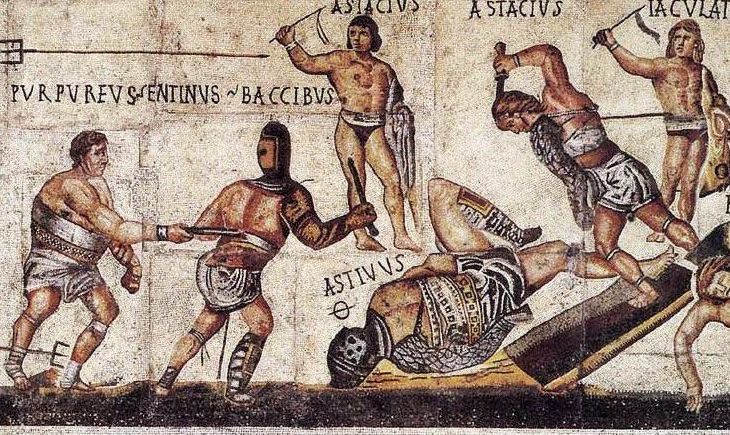

Gladiators in the Colosseum were not a single, uniform group, but specialists - each trained in a distinct genus defined by armour, weapons, and fighting style. These types were carefully matched to create contrasting contests, and included the heavy-armed murmillo and the agile retiarius, the exotic Thraex and the Greek-styled Hoplomachus amongst others.

Such distinctions went beyond sport. Each type carried cultural associations Roman audiences instantly recognised. The murmillo’s helmet recalled a legionary’s, the Thraex’s curved blade evoked Rome’s old Thracian foes: each part of a structured, symbolic language of combat. Understanding their origins, equipment, and tactics offers a clearer view of the spectacles that made the Colosseum central to Roman public life.

Read on for a detailed look at some of the main gladiator types - their appearance, weaponry, fighting style, and the cultural meanings they carried into the sands of the arena.

Murmillo

Big shield, bigger swagger. The murmillo strutted into the arena behind a tall rectangular scutum (shield), his heavy crested helmet enclosing the face and broadcasting his persona clearly even to the nosebleed seats. Murmillo is Latinized from the Greek for a type of saltwater fish, which explains the acquatic motif that frequently adorned his helmet. The helmet’s grille severely limited his vision, so a murmillo had to rely on brute strength, thick armor and endurance in combat.

The look drew on the gear worn by Roman legionaries; typically tall, rangy and very muscular, the murmillo embodied Roman military virtues: endurance, discipline, and controlled aggression. Crowds admired the murmillo’s strength and stamina, especially in long, punishing bouts, and his presence on the sand must have brought to mind the discipline of the empire’s mighty armies: as imperial propaganda, the type read as “Roman order” made flesh.

Thraex

If the murmillo was the embodiment of Rome, then the Thraex was the glamorous “other.” Thracians were famed as fierce barbarians, hailing from the region of modern-day Bulgaria (Spartacus the slave‑revolt leader was himself Thracian). Romans had a habit of outfitting gladiators as conquered enemies, and that ethnic othering made the Thraex an exotic favorite amongst Roman crowds.

He carried a small square or round shield (parmula) and a wicked curved sword known as a sica, designed to hook past a foe’s shield or helmet. His own visored helmet was high crested and culminated in a stylized griffin, making him look like a bronze statuette come to life. Fights involving Thraex were likely typically cat-and-mouse affairs: darting footwork, shield feints, and surprise angles to carve at thighs or back with his short sword.

Retiarius

Photo by TimeTravelRome via wikimedia commons, CC BY 2.0 license

Lightly armored and quick-footed, the retiarius (“net-man”) was the most unconventional gladiator in the arena - and perhaps the most controversial. Armed with a weighted fishing net (rete), a trident (fuscina), and a dagger, he wore no helmet and only a padded shoulder guard (galerus) on his left arm. A simple loincloth was the only thing preserving his modesty. His near-nakedness and reliance on subterfuge in the ring led to the retiarius being considered unmanly and lower in status compared to other gladiator classes. The writer Juvenal sneered at an effeminate aristocratic youth who disgraced himself by taking up the retiarius’s arms.

The retiarius’s strategy relied on mobility and timing. He would circle his heavily armored opponent, looking for an opening to entangle him in the net before thrusting with the trident. Against a murmillo or secutor, this made for a classic duel of speed versus strength. Though some saw him as lacking the gravitas of heavier types, the retiarius drew fascination for his theatrical style. He was both hunter and bait, an underdog whose survival depended on skill, timing, and the ability to turn the Colosseum’s sand into his own element.

Secutor

Photo by Kleuske, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

The secutor (“pursuer”) was designed as the retiarius’s nemesis. His smooth, rounded helmet had tiny eyeholes and no decorative crest - a deliberate counter to the retiarius’s net, which might otherwise snag on protrusions, and trident, whose prongs couldn’t slip through the narrow grill. This gave the secutor a faceless, relentless look, enhanced by his silence behind the narrow visor.

Equipped like a murmillo with a large scutum, short gladius (sword) and manica (arm guard) on the sword arm, the secutor’s fighting style was pure forward pressure. The secutor’s restricted helmet reduced airflow, making prolonged fights dangerous, especially under the midday sun. Exhaustion was his biggest issue, and something the retiarius was well equipped to exploit. This vulnerability heightened the drama for spectators, who could see the pursuer’s own endurance tested as much as the hunted man’s. In Rome’s carefully choreographed spectacles, the secutor was the implacable force to the retiarius’s cunning.

Hoplomachus

Photo by Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Styled after a Greek hoplite soldier recalibrated for showmanship, the hoplomachus fought with a small round or square shield, long thrusting spear and a backup dagger. His impressive bronze helmet had a high crest and broad brim, recalling Hellenic styles, and he wore full greaves on both legs as well as a manica on the weapon arm.

In combat, the hoplomachus’ main advantage was the length of his spear, which gave him a notable advantage in reach over his opponents. With it, he would thrust or feint before closing in with the sword. This made him effective against heavier types like the murmillo, whom he could harry before striking. The hoplomachus’s Greek styling had a nostalgic appeal for educated Romans, linking the games to the heroic age of the Trojan War.

Provocator

Photo by BS Thurner Hof, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

The provocator (“challenger”) was the arena’s master of the mirror match - a gladiator who faced only his own kind. His kit echoed Rome’s legionaries more than any other fighter: a large rectangular scutum, a short, double-edged gladius, and a small rectangular pectorale that shielded the chest without hindering movement. A single greave on the forward leg, a metal or leather manica on the sword arm, and a crested or plume-topped helmet with broad brim and visor completed the look.

Because both combatants wore identical armor, provocator duels were contests of pure technique. Timing, feints, and stamina mattered more than exploiting mismatched gear. The heavy defensive loadout encouraged methodical advances, and bouts could grind into tactical wars of attrition. The provocator may have lacked the exotic flair of a Thracian or Hoplomachus, but he offered something rarer: the disciplined, balanced duel where victory came from the man, not the mismatch.

Scissor

The scissor was one of the most distinctive and visually arresting gladiators in the arena. Although ancient sources are frustratingly vague, scholars believe that his name, meaning “cutter” or “carver,” refers to a unique offensive weapon: a heavy, bladed or crescent-shaped tube fitted over the forearm. It's likely that this arm-guard was a kind of tapered metal cylinder, closed at the end except for a protruding, double-edged blade - an intimidating hybrid between a sword and a punching dagger. The weapon would have been well suited to hacking through the retiarius’s net or damage his trident’s prongs, making the scissor a natural counter-class to that lightly armed fisherman fighter.

His strange silhouette, gleaming forearm weapon, and aggressive forward-charging style probably made him an exotic curiosity, especially in matches against the elusive retiarius. The pairing gave audiences a clear narrative: the fisherman’s net versus the cutter’s blade - a duel between entrapment and pursuit.

Eques

Embodying Rome’s fascination with the equestrian class from which he took his name, the eques stood apart among gladiator types because he entered the arena mounted. Isidore of Seville noted that the equites “were the first to compete in the gladiatorial games, after the standards had entered the arena,” indicating that their bouts were part of, or followed on closely from, the opening ceremony. After initial mounted hostilities, the eques would often dismount to finish the fight on foot.

Their costumes emphasized agility and spectacle: a tunic or light armor, a brimmed helmet often adorned with feathers, and a short sword once the spear was set aside. Equites nearly always fought each other, creating duels of mirrored style rather than mismatched pairings. Their bouts were shorter, more graceful, and above all theatrical - designed to delight the audience with speed, precision, and showmanship rather than the grinding tests of stamina seen in murmillo or secutor contests.

Glossary of Gladiator Terms

- Arena – The sand-covered performance space in the amphitheatre where combats took place. The sand absorbed blood and provided footing.

- Munera – Originally meaning “duty” or “obligation,” it referred to gladiatorial games, often staged as funerary offerings or political displays.

- Ludus – A gladiator training school; the most famous in Rome was the Ludus Magnus, connected to the Colosseum by an underground passage.

- Lanista – The owner and trainer of gladiators, responsible for their purchase, upkeep, and match negotiations.

- Summa Rudis – The senior referee of the fight, often a retired gladiator, who oversaw rules and safety.

- Scutum – A large, rectangular shield carried by heavily armed gladiators such as the murmillo and provocator.

- Parmula – A small, round or square shield used by light-armed gladiators like the Thraex and hoplomachus.

- Manica – An armguard made of metal, leather, or linen strips, worn on the weapon arm for protection.

- Ocrea – A greave or shin-guard, often made of bronze, used to protect the lower leg.

- Galea – A helmet, often ornate, with distinctive crests, visors, or animal motifs identifying a gladiator type.

- Rudis – A wooden training sword; also given as a symbol of a gladiator’s freedom upon retirement.

- Missio – The granting of mercy, allowing a defeated gladiator to leave the arena alive. Opposite was sine missione - no mercy granted.

- Damnatio ad Bestias – Condemnation to death by wild animals, a separate spectacle often held in the same venues.

We hoped you enjoyed this primer to the gladiators who risked all for the entertainment of the bloodthirsty denizens of ancient Rome. If you want to learn more about the fascinating world of the ancient games in the spectacular surrounds of the Colosseum, be sure to check out our Colosseum tours!

MORE GREAT CONTENT FROM THE BLOG:

- How to Visit the Colosseum in 2025

- A History of the Colosseum

- Did the Colosseum Have a Roof?

- 5 Fascinating Facts About the Colosseum's Arena Floor

- The Colosseum Underground: The Deadliest Show on Earth

- Wild Animals in the Colosseum

- The Best New Tours of Italy in 2025

- Where to Stay in Rome in 2025: Areas and Hotels Guide