The Palatine Hill is a vital piece of the jigsaw puzzle that is Ancient Rome, but these spectacular ruins are far too often overlooked by visitors to the city en-route to the nearby Colosseum and Roman Forum. But the Palatine is where the long history of Roman civilization began, and where the powerful Emperors of the Imperial age ruled over one of the largest empires the world has ever seen. Rich in history and wonderfully evocative of that distant time, it is one of the must-visit sites on any trip to Rome. Find out what to see and get the lowdown on its fascinating history with our online guide.

Ancient Rome Tours

Explore the Ancient City

If the valley of the Roman forum offers a vivid insight into the progressive system of government that forms the basis for our modern democracies, the ruins of the massive Imperial palaces on the Palatine Hill that loom over it tells a very different story. The Palatine enjoyed an enviable position in the ancient city, overlooking the Forum and Colosseum on one side and with a spectacular view of the Circus Maximus on the other.

A leafy enclave far from the dust and chaos of the metropolis below, this was the Beverly Hills of the ancient world – a post-code up here meant that you’d really made it. Once home to the villas of well-heeled Roman aristocrats during the Republican era, it was here that the emperors of Imperial Rome constructed their mega-palaces (complete with private box from which they could watch the chariot games in the Circus far below).

The Palatine hill is in fact where we get our word palace from, and the excessive splendours of these massive structures make it easy to see why. It was also central to the cultural imagination of Ancient Romans, the space where the Roman world was conjured into being in 753BC.

A Short History of the Palatine Hill

According to ancient myth, the history of Rome begins right here on the Palatine hill, with a dark tale of fratricide. The story goes that an evil and power-hungry king ordered his infant nephews drowned, but the servant tasked with the job couldn’t bring himself to carry out the heinous deed. Instead he placed the young Romulus and Remus in a reed basket and floated it downstream, leaving their fate to the gods.

Buffeted back to shore, a she-wolf happened across them and suckled them as her own cubs in her cave on the Palatine hill. Rescued finally by the shepherd Faustulus, the humble man and his wife raised the boys, who determined to found their own city on the banks of the Tiber. But whom did the gods favour to be its founder, and father of a dynasty?

The twins set to counting birds flitting across the sky, divine omens of favour. Romulus saw 12 to his brother’s 6, and triumphantly began to plow the boundary of his new city – but Remus was convinced the whole thing was rigged, and jumped over the new boundary to remonstrate.

Enraged at the transgression, Romulus murdered his brother. Rome, then, was a city consecrated with blood. The Romulan Huts, wattle-and-daub dwellings whose existence can be still made out from their foundations, reputedly mark his first settlement – legends aside, this is certainly one of the oldest signs of human habitation in Rome.

And so began the story of Rome. Ruled for the next seven generations by frequently vicious and authoritarian kings the people rose up against the last and most hated tyrant of the lot, Tarquinius Superbus. Revolting against his draconian rule, the monarchy was toppled and a republic founded in its place. Democracy of a sort had come to Rome, and held sway for the next 500 years – emblematised in the civic buildings and temples of the Roman Forum.

But as the Roman civilisation grew and grew, so did the power of the men who led its massive armies. Inevitably a power-struggle broke out amongst these heroes who had become bigger than the law itself, and civil war ensued. The victorious general Julius Caesar looked set to mould the city in his own image, but was assassinated by senators fearing the rise of a dictatorship. In the power-vacuum that followed Octavian rose to power and became Emperor Augustus, the first head of Imperial Rome.

The Palatine Hill is a sprawling archaeological site, rich in history but not always easy to navigate without some guidance. To help you make sense of it all, we’ve broken down some of the must-see highlights – those essential stops that offer the best insights into the lives of Rome’s emperors and help unravel the tangled thread of power, prestige, and architectural ambition that makes the Palatine Hill so special.

The Houses of Augustus and Livia

For the new emperor Augustus wishing to make his mark on the city over which he was now a quasi-divine ruler, the rich cultural significations of the Palatine made it a natural site for his new residence. What could be more symbolic than taking up lodgings on the very site where the legendary Romulus had founded the city centuries before?

And so the man who described himself as a ‘New Romulus’ added himself to the civilization’s glorious heritage by moving in to the Domus Augusti, whose series of small rooms unfold around two central peristyle courtyards. Between the courtyards was a temple dedicated to Apollo, further hinting at the new Emperor’s divine favour (some even suggest the Domus was built over the site of the Lupercal, the sacred cave in which the wolf suckled Romulus and Remus).

The surviving rooms contain beautifully preserved frescoes that vividly showcase the ancient Roman predilection for vibrant colours and elegant design. Masked figures cavort along the walls, interspersed with intimate still-lifes, fascinating architectural perspectives and geometric patterns in every shape imaginable. The nearby Casa di Livia, reputed to be the residence of Augustus’ wife on the basis of an inscription found scratched onto a lead pipe, also houses sophisticated frescoes of imaginary landscapes, mythologies, fruits and flowers.

The Palace of Domitian and Stadium of Domitian

The modest scale of Augustus’ relatively humble house is a startling contrast to the gargantuan pleasure-palaces his successors would build on the same site, financed by the spoils of war and the plunder of Jerusalem in 70AD (commemorated on the arch of Titus where the Palatine Hill meets the Forum). Nero, Tiberius and Septimius Severus all made their mark here, but the majority of the ruins still standing on the Palatine today are largely testament to the boundless ego of one man: Domitian. The son of Vespasian and brother of Titus, Domitian was by all accounts something of a lunatic. As the massive and opulent palace he had built for himself on the Palatine hill in 92AD vividly demonstrates, he was a megalomaniac too.

It was this palace, ‘awesome and vast’ to the eyes of the Emperor’s contemporaries and greater even than the sky itself, which remained the official residence of the Roman emperors for five centuries – but it’s days were finally numbered when a devastating earthquake finally sent it tumbling to the ground in the year 847.

The vast structure was a mix of public and private spaces and even included its own stadium, a kind of miniature Circus Maximus that was in reality a sunken garden surrounded by beautiful porticoes and studded with classical statues. At 147 metres long the Stadium was too small for horses, but perfect for foot-races and evening strolls. Seven laps of the stadium made up a Roman mile, and the Emperor was apparently assiduous in traversing it on the advice of his doctors.

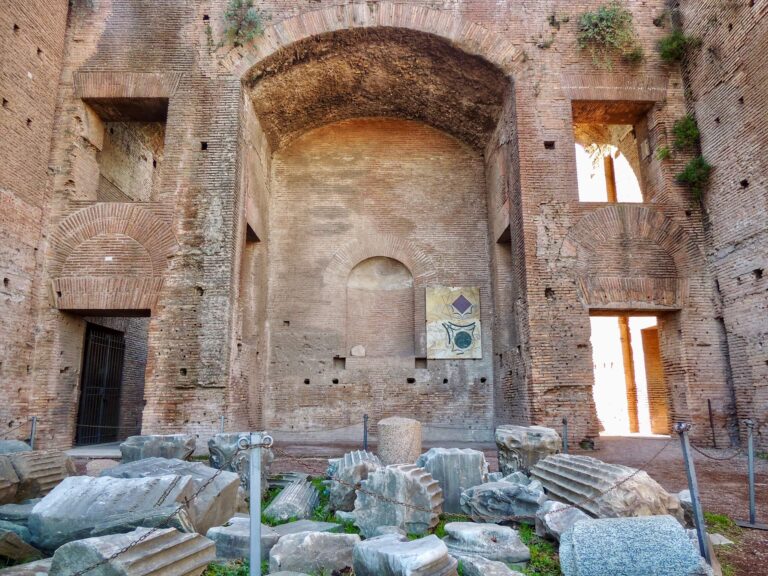

The Flavian Palace

The public area of the palace to the northwest, the Domus Flavia, was the heart of the complex where the emperor spent much of his day. Amidst massive vaulted halls, tranquil courtyards and tinkling fountains, the emperor hosted wild parties for the who’s who of the Roman elite. In the palace’s magnificent triclinium, studded with precious Turkish marbles and Egyptian porphyry still visible today, banquets often extended for 13 hours or more as guests lounged on couches and tucked into rare and exotic delicacies.

But all those peacock hearts, pheasants brains and flamingo tongues inevitably took a toll on the digestion – after the first 2 or 3 hours of gorging guests usually swallowed emetic pills, vomited into special jars held before them by waiting slaves, and recommenced the feast with gusto. It comes as little surprise that one emperor, the aged Antoninus Pius, died of indigestion after overdosing on alpine cheese.

Domitian reportedly liked to make his entrance to the festivities in an understated fashion: as he rode in on a chariot pulled by captive panthers, naked showgirls and acrobats entertained the diners. Sometimes things got out of hand. One account relates how a diner once suffocated to death under the clouds of rose petals that choked the air of the triclinium. At other times Domitian rigged his banquets as funereal rites in which the walls, furniture and even waiting slaves were painted black, and terrified guests ate off black onyx plates. To complete their terror, gravestones engraved with their names marked their places at the macabre feast.

The Throne Rome

Nearby the triclinium is the remains of the huge central hall of the palace, the Aula Regia, or throne room. Here the Emperor received the salutations of the city’s cowed aristocrats at dawn every morning from high up on a pedestal in a vaulted apse. Soaring columns of purple Phrygian marble carried a coffered cedar-wood ceiling more than 100 feet above the floor.

Flanked by massive statues of the gods carved in eerie green Egyptian stone set into niches in the walls, the self-proclaimed ‘Lord and God’ Domitian made his appearance veiled by a curtain-like some ancient precursor to the Wizard of Oz. Domitian was convinced he was the chosen heir to the goddess Minerva, who protected him from harm and whose shrine appeared in the palace’s every room.

To the side of the Aula Regia was the Basilica, so-called because its architecture provided the later basis for the design of Christian churches. This was in reality a court where the Emperor dispensed judgments on important legal matters and met with his advisors to discuss the key concerns of empire-building.

The Domus Augustana: The Emperor’s Private Quarters

Domitian’s excesses and cruelty meant that even Minerva’s intercession couldn’t permanently keep him out of harm’s way. As his paranoia intensified, the emperor retreated to the private spaces of his palace, the massive Domus Augustana whose two floors spread out around beautiful porticoed courtyards that connected it to the public spaces of the Domus Flavia.

In his private bedroom Domitian dreamt darkly that Minerva’s statue appeared to him and told him she couldn’t protect him any longer, before jumping off the balcony and shattering into a thousand pieces. The terrified Domitian polished the Cappadocian marble lining the palace halls to such a shine that he could literally watch his back for assassins, and he took to spearing flies with needles as they buzzed through the air to keep his reflexes sharp.

All to no avail: the Senate bribed his servants, who stabbed him as he slept. Exactly which of the surviving rooms played host to the dark deed remains a mystery.

The Cryptoporticus of Nero

Domitian may have been given to all the worst traits of human nature, but even he was no match for his predecessor Caligula. Caligula’s name has been a byword for insanity and sadism ever since his short rule from 37-41AD, and like Domitian he also met his untimely end amidst the palaces of the Palatine Hill. Caligula did his utmost to centralise power entirely on himself, murdering anyone and everyone that might threaten his absolute dominion.

His mental instability was legendary: amongst his more absurd actions were to raise his horse to the rank of senator, and nearly bankrupt the empire with the construction of an artificial bridge across the bay of Naples comprising thousands of warships lashed together. Caligula was often seen roaming the streets of Rome dressed as Zeus and carrying a thunderbolt, convinced of his own divinity.

Unable to bear his capricious cruelty any longer, Caligula was executed by his personal bodyguards at the behest of the Senate in a vaulted underground passage known as a cryptoporticus that linked the imperial palaces to one another. This was designed to allow the emperor to move between the palaces in relative security, but even its cover couldn’t save Caligula from his fate. The most impressive of these passageways still survives, the 130-meter long cryptoporticus of Nero that connected the Imperial palaces of the Palatine to Nero’s own Golden House, and is decorated with stucco and frescoes.

The Orti Farnesiani

Nearby are the lavish Renaissance gardens known as the Orti Farnesiani, built by the powerful Farnese family as one of Europe’s first botanical gardens on the site of the palace of Tiberius, Caligula’s father. Like Augustus’ own colonisation of the Palatine, the Farnese dynasty was making a clear statement of their exalted role in the history of Rome 1,500 years later, and even incorporated some of the palatial ruins into their shady retreat. Recently reopened to the public, the gardens boast commanding views over the Roman Forum and the city beyond.

The Museo Palatino (Palatine Museum)

If you haven’t had your fill amongst the ruins, behind the Domus Flavia the Palatine museum houses pottery, statues and pieces of architecture salvaged from the excavations of the Palatine Hill over the last 2 centuries. Pre-Roman Iron Age objects give way to terracotta friezes of the gods from Augustus’ Temple of Apollo and numerous portrait busts of Roman Emperors down the ages. Perhaps the most incredible artefact is a graffito from the third century that shows a man with a donkey’s head being crucified, a mocking reference to Christianity vividly showcasing the suspicion with which the new religion was viewed by the city’s still predominantly pagan populace.

Absolutely! Especially if you want the ruins to mean something. The Palatine Hill is one of the most important and evocative sites in ancient Rome, but without context, it can be surprisingly easy to walk right past its most fascinating corners. Unless you are an expert in archaeology, you’re bound to miss something without expert help.

A guided tour on the other hand – ideally with an archaeologist or expert in Roman history leading the way – transforms crumbling walls into imperial palaces, and scattered stones into the foundations of legends. You’ll uncover the layers of history that shaped this hill, from Romulus and Remus to Augustus and Domitian, while getting a clear sense of how the site fits into the broader story of the Roman Forum below and the Colosseum nearby.

With expert guidance, you won’t just see the highlights like the House of Augustus or the Farnese Gardens -you’ll truly understand them. Check out Through Eternity’s award-winning tours of the Palatine Hill here.

Tickets

Admission to the Palatine Hill is included in an integrated ticket that also includes entrance to the Roman Forum and the Colosseum, and is an essential companion to these famous sites. There are several options available depending on what you’d like to see:

- 24-Hour Ticket (€18.00) – Standard entry to the Colosseum (at a reserved time), Roman Forum, and Palatine Hill, plus access to any ongoing exhibitions.

- Full Experience Ticket with Arena Access (€24.00) – Includes everything in the standard ticket plus access to the Colosseum’s Arena floor and the SUPER sites (special locations within the Forum and Palatine Hill).

- Full Experience Ticket with Underground Access (€24.00) – Includes the Colosseum’s underground levels in addition to the Arena, Forum, and Palatine Hill.

- Forum Pass SUPER (€16.00) – Grants access to the Roman Forum, Palatine Hill, and Imperial Fora (but not the Colosseum). This ticket is valid for 30 days from the date of purchase and includes access to SUPER sites.

For more on the Roman Forum Super Sites, check out our guide to these special extras here: How to Visit the Roman Forum Super Sites.

Opening Hours

The Palatine Hill is open daily, with hours varying by season:

- March 30 – September 30: 9:00 AM – 7:15 PM (last entry at 6:15 PM)

- October 1 – October 25: 9:00 AM – 6:30 PM (last entry at 5:30 PM)

- October 26 – December 31: 9:00 AM – 4:30 PM (last entry at 3:30 PM)

Check official sources before your visit, as hours may change due to special events or maintenance. The site is closed on December 25 and January 1.

Who is entitled to free or discounted entry?

- EU Citizens (18-25): €2 for standard tickets.

- Children under 18: Free admission.

- Free Entry Days: The first Sunday of every month, April 25, June 2, and November 4.

Should You Buy Tickets in Advance?

Yes – advance booking is highly recommended! Along with the Colosseum and Roman Forum, the Palatine Hill is amongst Rome’s busiest attractions, and tickets frequently sell out – esèpecially if you are combining your visit with the Colosseum. Although there are ticket offices on site, this should be a last resort – buying online ahead of time guarantees your entry and helps you skip long ticket queues.

A thorough visit takes around 1.5 to 2 hours. If you’re combining it with the Roman Forum and Colosseum, plan for 3-4 hours to take in all the highlights. You will have a much better experience here if you don’t need to rush!

The easiest and quickest way to get to the Palatine Hill is by taking the B Line of the Metro to the stop Colosseo. Exit from the station and cross the road, always keeping the Colosseum on your left. From here it’s a 5-minute walk past the Arch of Constantine to the entrance on Via di San Gregorio, on the right-hand side of the road. Alternatively the 75 bus runs from Termini to near the entrance, whilst the 3 and 8 trams connect other parts of the city to the Colosseum – just a few minutes’ walks from the Palatine Hill.

If you want to visit the Roman Forum first, then you can access the Palatine Hill directly from the archaeological site by climbing the stairs in the Farnese gardens.

Book Your Ancient Rome Experience